reputation: the Currencci of Opportunity

“Closing debts may indeed be expensive, but it is infinitely more so to withhold payment.”

- Robert Morris, 1785

Everyone values reputation. It is an extension of ourselves; our reputation both proceeds us and leaves a lasting impression. It gate-keeps trust and begets opportunity. Difficult to build and easy to break, we inherently understand how reputation underlies all interactions from inter-national to inter-personal affairs.

Nowhere is reputation more explicit than finance, where it is neatly quantified as ‘creditworthiness’. This heuristic influences every financial exchange - why transact with an unreliable counter-party? Evaluating reputation via creditworthiness allows decision makers to better ascertain risk and forecast outcomes. Applications are countless and include underwriting, employment decisions, mergers, trade financing, acquisitions, and more. This makes a good economic reputation essential for success in business, and by extension, the modern world.

Despite its importance creditworthiness is relegated to a paradigm developed over 70 years ago. The world has changed and an update is desperately needed. It is time to fundamentally rethink reputation, creditworthiness, and establishing trust.

understanding reputation

Deconstructing creditworthiness requires first understanding reputation’s fundamentals. For one, it is universal. From countries to businesses to people to animals to concepts to everything in-between, reputation influences all the world’s relationships:

- “I love my Vitamix blender, it has lasted 20 years.”

- “He’s a flake”

- “That puppy likes to lick!”

- “He’s more Catholic than the Pope!”

- “She’s a Conservative?!”

- and so on…

But what is a reputation? A formal definition declares reputation as “the overall quality or character as seen or judged in general.” In other words reputation is the observation of innate character and the resulting expectations, rather than the character itself. In this way a reputation is not necessarily an accurate reflection of truth, but is instead subject to the limitations of observation. For instance, a strong conviction or impression may result in a reputation completely dissociated from the underlying character it represents.

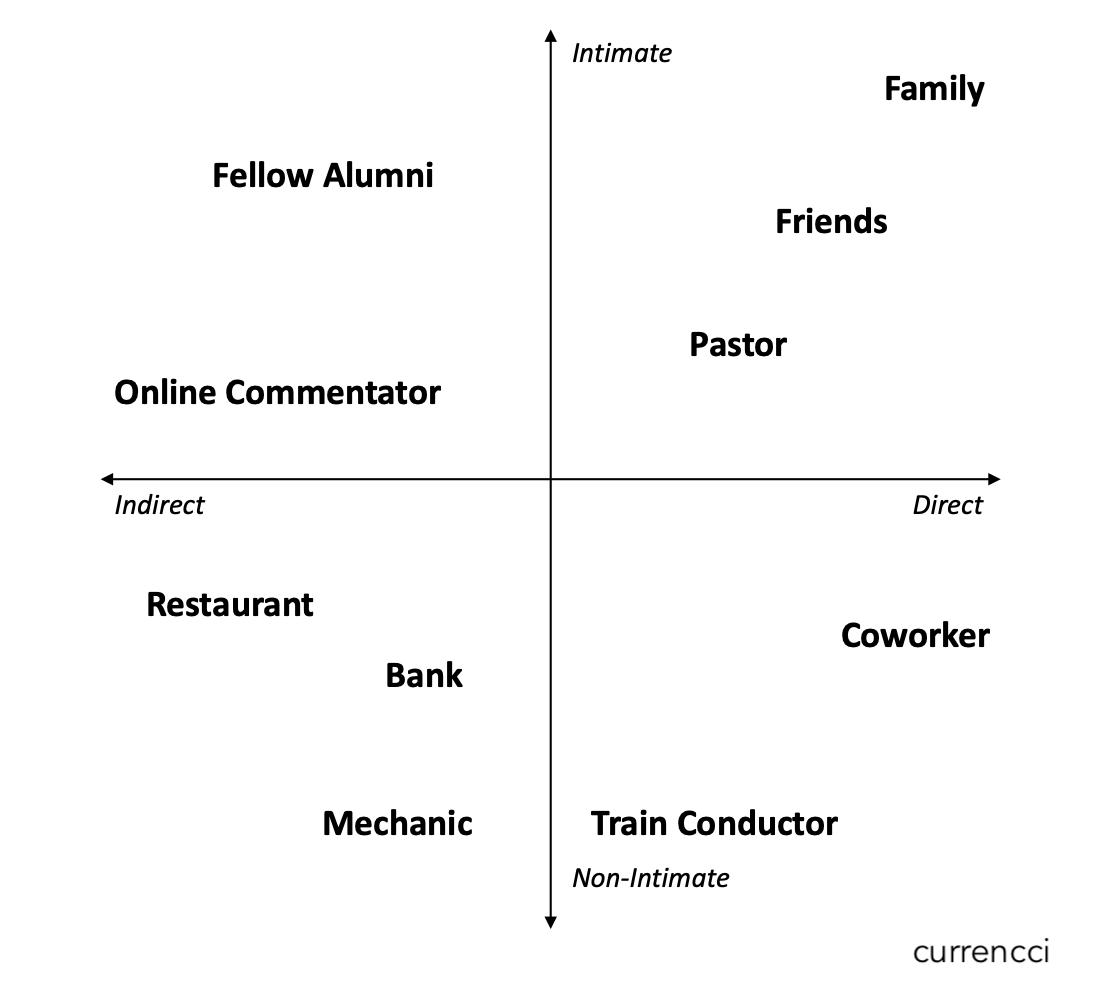

Reputations are built through through factual or unverifiable observations. Factual reputations are more accurate but take far longer to build. A familiar dog acts sweetly; a student’s transcript doesn’t lie; a reliable blender doesn’t break. Unverifiable reputations are less accurate but easier to build. A stranger says their dog doesn’t bite; a letter of recommendation refers an applicant; a waiter pitches an entree. In practice, intimacy and relevance determines which reputation-building method an observer uses[1].

Figure 1: A sample spectrum of direct versus indirectly built reputations.

Figure 1: A sample spectrum of direct versus indirectly built reputations.

Reputation pervades decision making which in turn drives individual behavior. Favorable terms are granted to those with known, positive, and strong reputations in favor of those with unknown or poor ones. Consider Michelin restaurant reviews. In such a framework all entities are incentivized to meet others’ expectations to receive favorable reputations, and subsequently positive interactions. A restaurant serves great food, builds a strong reputation, earns good reviews, and wins more business. This desire to build ‘positive’ reputations amongst different audiences leads to multifaceted - even potentially self-contradictory - behavior. Imagine the restaurant who caters to tourists rather than locals.

Reputation is self-fulfilling and difficult to shift. As the world interacts towards an entity based on a reputation, so does the recipient’s character align with that mold. A well-treated dog grows friendly; a carelessly operated blender breaks. Intriguingly, a positive reputation is easy to change, whereas a negative one is difficult to buck. Why? Behavior considered ‘bad’ tarnishes reputation in a way ‘good’ behavior fails to cleanse it. It is easy to recall public figures who have fallen from grace. Likewise, reputations are easier to shift in larger increments than smaller ones. Dramatically unexpected behavior forces observers to rethink their overall perceptions whereas smaller shifts are easier to miss. Consider the liberal politician who defects from their party versus gradually voting more conservatively.

Reputation is thus resilient. Small individual aberrations from one’s reputation are usually judged as just that, and do little to diminish the overall perception of one’s character. The more well-established a reputation, the more difficult it is to upset. This can result in preposterous situations, where perception beats reality. A recent example is the high reputation of Bernie Madoff as a financier prior to his ponzi scheme coming to light. While outrageously inaccurate reputations may last for some time, most are eventually corrected over time. Consider the recent re-evaluations of many historical figures, such as Robert E. Lee.

It’s worth noting reputation’s relationship with trust and identity.

Whereas reputation is the perception of past behavior, trust is the future conviction of that perception. A dog with a friendly reputation is trusted to play with a baby. Reputation’s expectations may spark a decision, but trust is what executes it. Trust further plays a role in reputation building - unverified reputations built with trustworthy sources are far stronger than those built without.

Identity is equivalent to character while reputation - as stated earlier - is the perception of it. An individual has agency over their identity but ultimately limited control over their reputation. For example a man may identify himself by his personal hobbies but is known by his professional reputation. Dissonance between identity and reputation causes issues. Nobody likes to be stereotyped or pigeonholed into who or what they aren’t. Typically this is caused by building reputations in an unverified manner with poor root information. Unfortunately identity is often eclipsed by unverified reputations - consider the influence of unsubstantiated Yelp ratings on a restaurant’s business.

reputation in finance

Reputation’s core principles carry through to finance. Here an entity’s ‘economic reputation’ - or ‘creditworthiness’ - is based purely on measurable, quantitative behaviors and explicitly used for decision making. The paradigm for building, measuring, and sharing creditworthiness is now entrenched throughout the developed world and plays a major role in modern commerce.

the history of credit

Creditworthiness’ importance has been understood for centuries. From ancient times to the present, entrepreneurs have relied on qualitative measures like letters of recommendation to secure business opportunities. However this has always been an imperfect method - not only do qualitative heuristics risk forgery and fraud, but they also lack standardization. The inability to establish trust within a market ultimately limits the economy to business interactions between known partners and hampers new ventures. Fortunately, two major industry evolutions have transformed how creditworthiness is measured and applied.

Creditworthiness underwent its first major evolution in the mid-1800s with the emergence of credit bureaus. Around the time of the U.S. Civil War information collection and storage had progressed to the point where entrepreneurs were able to assemble dossiers on the creditworthiness of most businesses and prominent individuals. These providers came to be known as bureaus, whose reports enabled decision makers to make informed business choices. Over time two distinct forms of ‘credit bureaus’ emerged: consumer-focused, and business-focused.

The credit rating industry is concentrated. In the United States for example, Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion dominate consumer ratings, while Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch dominate business ratings. This is due to the historically high fixed costs of standing up a comprehensive ratings agency - keeping track of all consumers or businesses in an economy is complicated! Furthermore these incumbents possess brand cachet and longstanding customer relationships. However, with the rise of digital technology and open banking these barriers are falling…

Creditworthiness’ second major evolution was its basic standardization. The United State’s Fair Credit Reporting Act in 1970 provided guidelines on what data could be used in evaluating consumer creditworthiness and how those conclusions could be stored and shared. Further standardization came when the U.S. consumer-focused bureaus agreed to use an algorithm developed by the FICO company to translate their respective dossiers into quantitative ratings[2], thus creating the ‘consumer credit score’. This rating heuristic has now become the universally accepted measure of an individual’s financial reputation. Though consumer-focused, these innovations have since increasingly bled over to the business-oriented side of the industry. Credit ratings standardization has greatly expanded creditworthiness evaluation and use.

Note for simplicity’s sake this essay focuses on credit ratings in the United States. These same methods are generally consistent throughout the developed world.

assessing creditworthiness today

This leads us to the present, where ‘credit ratings’ are the universally accepted measure for evaluating economic reputation. This makes them an inescapable component of modern life, and immensely influential upon the financial opportunities available to a given individual or business. Bad rating? Don’t expect to rent that space or secure that loan. The repercussions are so severe a multi-billion dollar industry has sprouted up on ‘repairing’ poor credit ratings. Their centrality to modern economic life places paramount importance on the soundness of bureaus’ outputs.

Credit ratings’ legitimacy are built on the assumption that key past financial behaviors are indicative of future ones. On this premise bureaus assemble certain types of financial behaviors for review. This is limited to easily collectible data, and mainly consists of reports from registered creditors and public records. For instance, collected data points would include past loan repayments, potential bankruptcies, and number of bank accounts. More nuanced aspects of a consumer’s financial life - such as their income, total assets, or spending profile - are not included for evaluation. The limitation is intentional to an extent - sources aim to be objective and verified. A registered creditor is far less likely to present inaccurate data to a bureau than a fly-by-night startup. However, bureaus ignore many otherwise valuable data sources given the high cost of collection and verification.

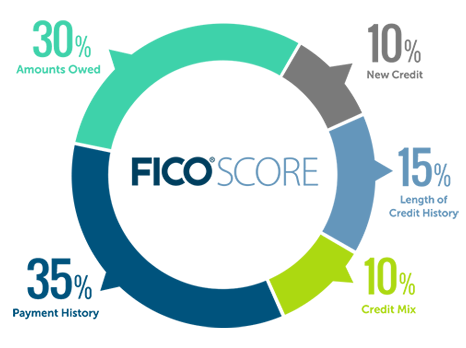

After aggregation behaviors are quantified, assigned weights, and run through an algorithm to produce a credit rating. This is as much an art as a science posing many difficult questions: does one financial behavior indicate creditworthiness better than another? How can a bureau discern poor luck from poor judgement? Are relative changes more important than absolute ones? Does a credit rating reflect only the statistical likelihood of loan repayment, or something more? Regulatory guidance has provided cover on some of these questions, while bureaus have adopted common scoring methods in an attempt to address the remainder. Generally speaking, bureaus make the best of their input data to score and aggregate behaviors according to how well they indicate the ability of an entity to repay a loan without default.

Figure 2: Example components of the FICO consumer credit score.

Figure 2: Example components of the FICO consumer credit score.

Credit ratings for larger organizations, or even countries, includes custom input in addition to standard measures. In these instances the rating process typically involves a team of analysts manually reviewing the entity’s public and non-public financial data, interviewing key stakeholders, and presenting a report to a specially convened ‘ratings-committee’ which assigns the final grading. Intriguingly, given the cost to create such scores they are often commissioned by the rated entity (dubbed the ‘issuer’ in industry parlance) for sharing with external parties (e.g. investors, creditors, etc.).

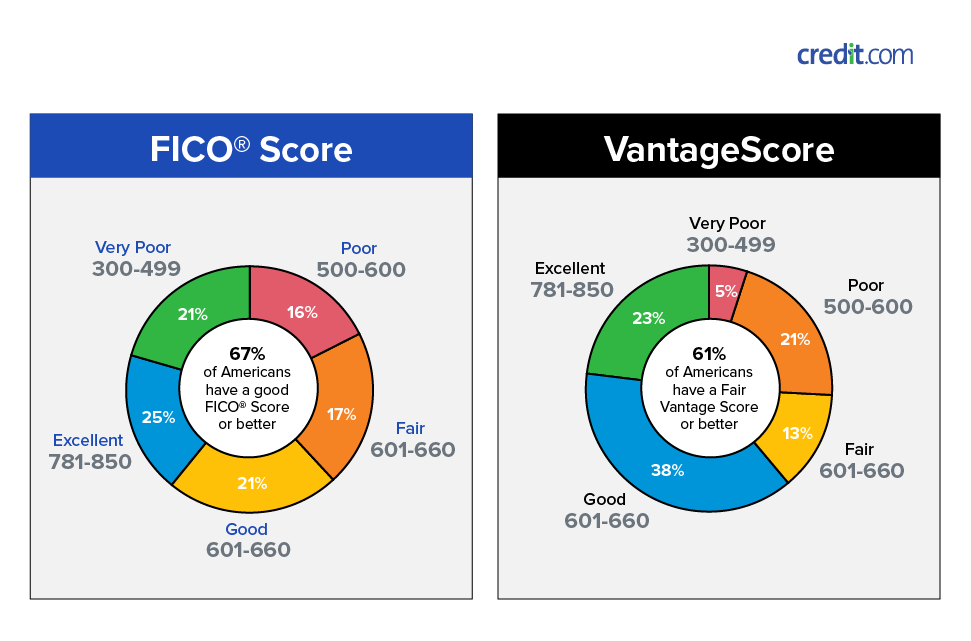

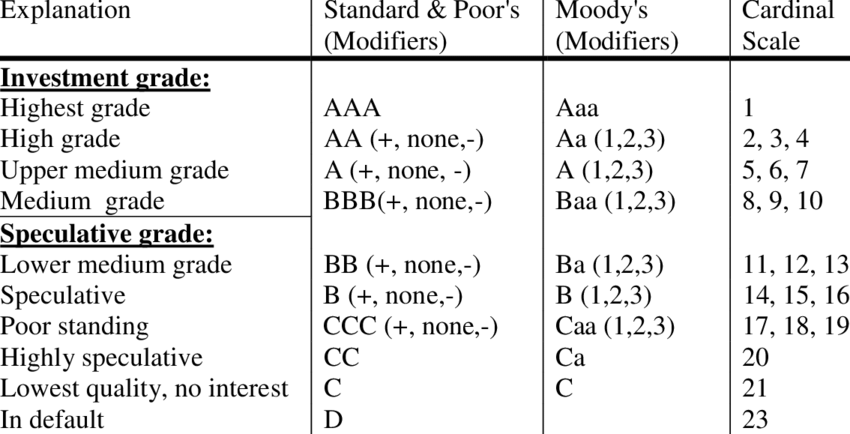

Final score presentment is generally similar between both consumer and business ratings. The finalized score is presented in a report alongside a contextual rubric explaining its general meaning. In addition to the headline rating, bureaus generally provide supplementary statistics and highlights. For instance, a report may include notes on past bankruptcies, liens, and missed loan payments. The report recipient can then use provided information to make their decision.

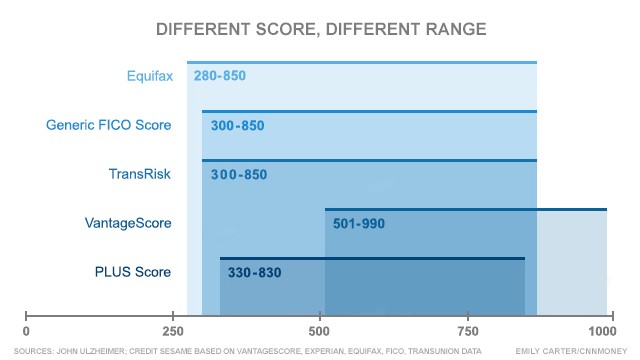

Figure 3: Example of how credit ratings confusingly vary by bureau, despite attempting to say the same thing (e.g. “Good”, “High Grade”, etc.). Top: Competing U.S. consumer ratings. Bottom: Competing U.S. commercial ratings.

Unfortunately making such decisions based on these ratings is not at all straightforward, as modern credit scores and associated rubrics are incomprehensible. Since the introduction of the standardized FICO score in 1989, bureaus have introduced multiple scoring systems, with seemingly arbitrary scoring ranges (e.g. 300-850 for consumer reputations or D through AAA for businesses), and numerous variants. Furthermore, how these scoring methods work is kept secret. For instance, FICO notes their algorithm components and weightings vary depending upon the recipient. The variety also causes confusion as a scores vary between systems. Is one’s creditworthiness better represented by one score versus another? Merely asking raises the broader implication of whether outsourcing rating reputation is relevant if one can’t trust - let alone understand - the results? A system conceived to reduce complexity has itself become convoluted.

Figure 4: Example of scoring confusion.

Figure 4: Example of scoring confusion.

The cause is ironic. As bureaus have predicated their business as arbiters of creditworthiness, they have committed themselves to a narrow definition of relevant behaviors (i.e. loan repayments) and have effectively commoditized themselves. Now they seek to differentiate, but not too much from their existing offerings. With only so many data points available, there are limited methods of interpretation. Instead, as exemplified by the plethora of scores and systems, bureaus have turned to marketing and other superficial methods to stand out from peers while retaining their core offering.

Regardless of the rating systems used, bureaus’ business models have remained virtually unchanged since their founding. A customer seeking the creditworthiness of an unfamiliar entity pays the bureau for their assessment. Credit ratings now pervade the economic decision making surrounding most business interactions, particularly amongst unfamiliar entities. Consider all the loans and credit cards decided within seconds for consumers and small businesses. In most instances these assessments are requested digitally and only reviewed manually in edge or high-touch situations.

The simple methods behind how the industry creates ratings, its business model, and the commoditized output belies its high profit. Today a credit pull costs ~$15 on an individual, and ~$100 for a small business. With millions of credit ratings requested daily, this quickly adds up. In 2021, the consumer credit rating industry in the U.S. alone had a $14B market cap. Originally the high pricing for credit ratings was a function of cost. Founding and running bureaus was prohibitively expensive for new entrants. Over time these costs shrank as data feeds were digitized and automated. Now with variable costs so low, the cost of a ‘credit rating’ is dictated more by competitive dynamics and marketing than by any real hard costs.

To illustrate how the modern creditworthiness model functions, consider the hypothetical example of an individual buying an apartment. First, the individual applies for a loan from their bank. The bank (typically) informs the individual it will conduct a ‘hard inquiry’ (though businesses can generally perform such checks without consent) which may impact the individual’s score. Upon receiving the score from the bureau (either via a digital API or PDF report), the bank uses the score as an input to its underwriting model. Credit ratings generally have a high weighting in the loan outcome. If approved, the bank submits a notice to all three major U.S. Bureaus, notifying creation of a new line of credit for the individual, along with the amount.

ongoing evolution in assessing creditworthiness

Accurately portraying creditworthiness - and one’s economic reputation - is a subject of growing interest. Investors and entrepreneurs alike argue too many worthy entities are denied financing by the existing credit rating system. Rather, they see opportunity in expanding economic opportunity by enhancing existing methods of judging credit. The so-called ‘alternative credit scoring’ sector is popular - a recent tally includes 222 start-ups in the space, and the list keeps growing.

As of publishing the vast majority - if not all - of new entrants in the credit rating space differentiate themselves from incumbents by relying on incremental data sources long ignored by legacy bureaus. Most frequently cited data points include payment behavior, particularly of various bills (e.g. cellular, utilities, rent, etc.), demographic data, app data usage, and online browsing history. They argue additional digital footprints are just as valid - if not more so - than the limited set of financial behaviors incumbents have relied upon for so long. What may have been relevant fifty years ago is not an appropriate creditworthiness heuristic for the modern entity. Consider the millions of unbanked and thus un-rateable people and business who are economically trustworthy.

Most alternative credit providers also tout their use of machine learning (i.e. ‘Artificial Intelligence’) in calculating credit ratings. They claim their advanced modeling is superior to that used by incumbents. This is dubious. Bureaus and legacy rating providers like the FICO corporation have built their business on quantitative scoring. Machine learning is simply advanced statistics - that legacy providers are ignorant of cutting edge mathematics is unlikely. Instead, new entrants posses a higher risk tolerance than the bureaus for over-scoring recipients with generous ratings. An established multi-billion dollar bureau with a massive customer base has more to lose with inaccurate scoring than a start-up with only a few.

For all their innovation however, nearly all newcomers follow the same basic business model as the legacy bureaus. A customer wants to know the creditworthiness of another entity, the provider shares an evaluation. As new as they are, incremental data streams and better scoring algorithms don’t seem a long-term competitive advantage versus incumbents. Furthermore, they lack the traditional banking data feeds of their incumbent rivals. It is only a matter of time before legacy bureaus catch-up by developing new or enhancing existing offerings. Meanwhile, they are likely to have retained deep relationships with their massive customer bases.

the credit rating system is broken

Our current system for rating creditworthiness is irreparably out-of-date. What was relevant in the mid-1800’s has slowly grown further and further away from the needs of modern commerce. Yes - credit ratings have and continue to enable countless business interactions, but how they do so precludes multitudes from the financial system as well as imposes undue burden upon society.

To start, modern credit ratings are weak and inaccurate due to poor input data. The ‘garbage in, garbage out’ data mantra is well-applied to the credit rating industry. In the U.S. 20% of surveyed consumers reported errors on their credit reports, while in the UK nearly 38% of consumers found discrepancies. Minimal contextual information also harms rating accuracy. Bureaus don’t account for macro-economic trends or other externalities that may affect your immediate creditworthiness, but not overall long term economic risk. For instance, current models treat a missed loan payment because of COVID the same as one missed due a poorly run business. Limited input data means an entity’s true economic reputation isn’t captured.

High costs associated with collecting financial records means some bureaus consider more information than others, causing scoring variances and hampering industry competition. Lenders and other reporting organizations must pay fees and undertake onerous set-ups to report to bureaus. They do so in order to provide some recourse (i.e. a creditworthiness black mark) if their clients default. They are ill-incentivized to bear additional costs to begin reporting to additional recipients. Credit ratings from new entrants suffer as a result. A recent study found a major incumbent had more accurate scores than a smaller agency due to superior input data. New entrants relying on ‘alternative data’ may offer compelling scores, but without a holistic view an entity’s true creditworthiness cannot be measured. Its worth noting these alternative credit providers typically ingest the reports of the incumbents - a useful workaround, but one inherently limited to their rivals’ flaws.

Credit ratings are commonly out-of-date, forcing resulting decisions to use incomplete information. Bureaus are slow to incorporate relevant information or correct errors, with corrections to consumer scores taking up to six weeks to appear. Further, scoring algorithms do not appear to weigh behavior differently based on recency. As such long-past circumstances or actions can weigh down the rating of an otherwise economically trustworthy entity.

Creditworthiness algorithms are also fallible. The major rating systems algorithms have remained relatively unchanged for decades. Consider the FICO score, which has remained virtually unchanged since 1989. Major rating systems are also calibrated to measure against an ‘ideal’ archetype non-representative of the broader population. For instance, consumer scores are built around behavior typical of a homeowner, with mortgage and car payments serving as key inputs. Urban consumers are thus intrinsically rated worse off. That all entities are treated identically according to a single-faceted rubric grows even more troubling when race is taken into consideration. People of color in the U.S. are significantly more likely to have lower credit ratings than the national average, as models were originally calibrated on middle class whites.

Measuring creditworthiness with a single rating for all economic circumstances is overly simplistic and fails to meet the complexity of the real world. An entity may have a lower risk of default for certain types of credit than others. A taxi driver will be more likely to prioritize their car loan over mortgage. Alternatively, in a commercial setting more favorable terms should go towards improving the core business rather than entering unrelated new areas. A one-size-fits-all-entities-and-circumstances approach needlessly prevents worthwhile loans from being made and limits overall economic interactions.

Consumers consider ratings confusing and inscrutable, prompting many to disengage. Roughly 40% of surveyed Americans don’t know their credit score. More than half never check their scores at all. The volume of search engine queries on basic questions such as “how does my credit score work?” and the like is growing steadily year over year. With all the score variants, who can blame them? Many end up in despair. Consumers have little proactive control over their scores beyond the exploitative credit repair industry and feel entrapped by the bureaus.

Consumer helplessness is compounded by the poor customer service and security of major bureaus. Consider how legislation mandates the three major U.S. bureaus to make credit reports available for free annually to all consumers. However, accessing such reports is overly difficult and buried behind layers of hard up- and cross-sales advertisements. General access to scores are gated by fees. Why should a consumer pay a fee to access a score about themselves made without their permission, composed using their private financial data? To top it off, bureaus’ data privacy protections are lacking. Consider the recent Equifax hack which compromised the private information of 147 Million, or roughly 44% of the U.S. Population. Or, more recently, how an Experian vulnerability exposed the credit scores of most Americans. All three bureaus quickly moved on this calamity by offering new auto-renew subscription based data protection services, while continuing to deny basic security for ‘free’ accounts.

On the commercial ratings side, the major business model for assessing organizations is broken and subject to conflicts of interest. The main reason being that rating recipients (i.e. ‘Issuers’) tend to pay for their own reports. Research shows recipient-funded ratings are inflated compared to those paid for by third-parties (e.g. investors). Recipient-funded ratings incentives bureaus to award over-generous ratings to keep business and commissioning recipients to ‘shop’ for multiple scores in order to land the most favorable one possible. The confidence commercial scores provide can also be deceiving - overinflated bureau ratings were a key contributor to the 2009 Financial Crisis.

Commercial ratings are also vulnerable to the subjectivity of the analysts creating them. To start, the person doing the rating may be biased, whether consciously or not. Research has found analysts’ political preferences affect created ratings, particularly in election years. Furthermore, analysts may be assigned to a specific industry or set of firms, placing pressure on their personal relationships to offer generous ratings. To this point, research has shown commercial ratings are most accurate when first made. As the relationship between the recipient-rater strengthens over time, the score diverges with reality. Finally, analysts have no legal liability for inaccurate scores, making their work more subject to aforementioned influences.

Many interactions enabled by the current creditworthiness system shouldn’t necessarily occur. Modern lenders operate at a scale where pushing the boundaries of their risk tolerance adds incremental percentage points revenue, which in absolute terms can be tens of millions of dollars. Individuals suffer the price. Research has shown the financial sector’s increasing use of credit scores to stretch risk decisioning measurably drives significantly more, and higher value, bankruptcies. The creditworthiness market may be optimized, but only for lenders.

Worst of all, the broader credit rating model perpetuates socio-economic stratification. A poor credit rating begets higher fees and interest rates, further distressing an entity’s (typically a person) finances. The effect snowballs as individuals considered too risky by mainstream financial services are forced to transact with increasingly expensive providers (e.g. payday lending). Basically, bad credit ratings inflict a tax on those least able to afford it. From an economic perspective, this setup is technically rational and fair. However, when that person or business has lost their ability to pay due to an unexpected calamity (e.g. COVID-19, a personal tragedy, etc), is the system just? What about when an entire class of people or entities have lower credit ratings due to historic economic persecution (e.g. women, minority owned businesses)? Even if it is ‘economically fair’, is a system that punishes the most vulnerable the one we want?

Ultimately incumbent bureaus are trapped with their outdated business models and scoring methodologies. Simply put, they are afraid to be wrong! Their business is based on being correct, over time, always. Imagine the reaction bureaus would receive if they introduced new scoring methods which were more accurate, but produced ratings unaligned with those prior? With real innovation impossible to introduce, bureaus are now enslaved to their past.

how did it get this bad?

The creditworthiness system is so broken because our interaction model has completely flipped since its creation. In the past, credit ratings were for edge conditions. Most economic interactions were between known counterparts. Strangers required a closer look, which is where bureaus added value by providing a verified assessment. Credit scores’ failings were readily accepted given they only influenced a minority of interactions, which would have never even had the opportunity to occur without them. As recently as 1978 retailers and banks held the same amount of revolving consumer credit, because loans were driven by personal relationships than bureau assessments.

Today’s interaction model is the opposite. We are a world of interconnected strangers, who do business overwhelmingly more often with those we don’t know than those we do, meaning the creditworthiness system is now used for most significant economic interactions. The issue is plain to see - what was once relevant as a measure for assessing the risk of potential debtors is now used as the universal barometer of reputation. ‘Credit pulls’ are the deciding factor for prospective tenants, job applicants, utilities, large purchases, credit card applicants, and more. A ‘good’ score is essential to navigating society, regardless of whether or not it accurately reflects one’s true financial character. Now ubiquitous, the bureau systems’ inherent failings are an unavoidable feature of modern life.

Furthermore, in this environment the power dynamic has shifted from rating recipient to rating requestor. In the past requestors leveraged bureaus to assess unknown entities because only few other viable business counterparties were available (otherwise the requestor would do business with a known entity). Recipient counterparts with high bureau ratings were thus exposed to business opportunities which would have otherwise never occurred. Today, thanks to globalization and information technology requestors can now quickly evaluate thousands of potential recipient counterparties. With direct reputations difficult to establish and ratings what they are, recipients struggle to have themselves accurately portrayed and win favorable terms for interactions they must undertake.

a quick recap

- Credit Scores were originally devised as a mechanism to ascertain whether or not an entity could repay debt

- The industry arose from investigatory ‘bureaus’ which collected publicly available information to form unique dossiers on every individual and commercial entity they could

- Over time the creditworthiness industry has grown deeply entrenched and concentrated juggernaut powered by automated data collection and algorithmic scoring

- The creditworthiness system has settled into a paradigm of ‘ratings’ (quantitative and qualitative, for consumer and commercial entities, respectively) primarily based on past loan repayment behavior

- Credit ratings are now embedded into modern society and essential for most significant economic interactions (e.g. loans, new B2B relationships, bond ratings, etc.)

- Unfortunately, the modern creditworthiness paradigm is subject to inherent flaws, including:

- Input data is non-comprehensive

- Credit scoring algorithms are overly simplistic, built on stale data, and intrinsically biased

- Ratings are opaque and difficult to understand

- The bureau business model is hostile to those they rate (e.g. accessing data without permission, losing data in breaches, charging for correcting errors, etc.)

- The commercial rating business model is prone to conflicts of interest and corruption

- Ratings today perpetuate historic inequities

- Incumbents are disincentivized to innovate, out of fear of delegitimizing themselves

- New entrants are attempting to address these flaws with ‘alternative credit scoring’, but as they operate within the existing system their effectiveness is inherently limited

- The creditworthiness system was built for an economy and types of business interactions which are increasingly out-of-date and irrelevant in the modern world

- Today’s system advantages rating requestors over rating recipients

building back reputation

Credit ratings have grown disconnected from what its original intention - an accurate reflection of one’s character. The modern creditworthiness system is built by and for requestors, not those whose reputations are represented. Those rated are ignored in today’s model and have very little control over how their creditworthiness is evaluated or shared.

This is madness. In today’s environment no one is more invested in a given rating than the rating’s recipient as it determines nearly all of their significant financial interactions. However, current systems are prone to inaccurate reflections of creditworthiness for a significant proportion of rating recipients.

Its time to redefine how we evaluate, share, and use economic reputation.

baby steps

The flaws of the modern creditworthiness paradigm are easily apparent, and there are a multitude of efforts to usurp it. However nearly all of these efforts appear doomed to fail. As described above, most startups merely operate within the existing system and perpetuate legacy issues. Of the remainder, a few offer serious challenges to the status quo and are worth deeper review; most notable examples include the Chinese Government and Alibaba, ‘boost’-type bureau offerings, and consumer-friendly startups like CreditKudos.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is foremost amongst world governments in recognizing the weakness of the current creditworthiness paradigm and taking innovative steps to address it. Their efforts are led by the vision of “building a high-trust society where individuals and organizations follow the law”, which they are pursuing through creation of a universal “Social Credit System”. With it, all entities receive a score which influences all their interactions with public and private services, from renting an apartment to winning a contract to receiving premium healthcare. The system launched nationally in 2020 in an intentionally fragmented manner, wherein the implementations vary dramatically region by region. Doing so allows for valuable learning and refinement towards an eventual nation-wide system. Its innovations are manifold. First, it is laser-focused on reflecting overall reputation (and character), rather than the ability to pay back a formal debt. Second, the system is truly universal by encompassing both individual and corporate entities. Third, the system possesses a holistic perspective, ingesting data sources from financial records to environmental impact to web-browsing history. Fourth, the system is intentionally designed for ubiquitous use throughout society.

Unfortunately these innovations are perverted by the CCP’s totalitarian aims. Concerns boil down to three main issues: (i) scoring is subjective, (ii) privacy is nonexistent, and (iii) application is tyrannical. A fair creditworthiness system should rely on objective, apolitical behaviors. The CCP has introduced punitive score knocks for trivial actions, including not visting one’s parents or walking a dog without a leash. An opaque ratings system that can change suddenly and is based on indisputably subjective behaviors is worthless. Further, scores are created and shared without recipient consent. Users should have agency over their data, its access, and application. Finally, the system is intended to influence access to basic rights. There is no reason someone’s credit rating should preclude them from taking a flight, or starting a business, or forming new relationships. An ideal creditworthiness system must respect the individual as much it benefits society.

As a side note, evidence suggests the massive 2017 Equifax hack was performed by the CCP. Other than private credit records, trade secrets and operational details were presumably exfiltrated. My unsubstantiated take - this information was used to inform the design of China’s new system.

China is also the source of the world’s most successful model of establishing trust between online strangers, invented by the technology giant Alibaba. In this model, individual interactions between strangers on a marketplace are protected by an escrow system wherein the payer is protected from fraud by only allowing fund disbursement once goods are received and inspected. Payees in return have marketplace access, and the ability to leave negative feedback on payers. Aggregate interactions are summarized into what are effectively ’trustworthiness scores’, a la credit ratings. Everyone in the marketplace knows their own score, why it is what it is, and has agency over it. This system kick-started an e-commerce revolution in China, and convinced the traditionally conservative Chinese consumer to trust and engage with strangers online. Limited only to an online marketplace, many of these concepts are well-suited towards a revised creditworthiness paradigm. While China’s systems are not perfect, they have introduced true innovation to a staid industry.

The incumbent bureaus themselves are finally attempting to innovate upon their scoring models by incorporating additional data sources. Experian Boost and UltraFICO allow consumers to potentially increase their credit ratings by sharing access to their checking, savings, and / or money market account records. Essentially, bureaus are using open banking and consumer consent to incorporate additional data into their scoring models. From a bureau and requestor perspective, this is terrific. Better data means better scores. However, this raises profound questions from the consumer perspective: (i) is my score inaccurate unless I consent to sharing my data; (ii) why don’t the bureaus have to obtain my consent for rating me in the first place; (iii) without my other financial information, is even this bureau score still inaccurate; and (iv) with such concerns are the bureaus even legitimate? While improving the scoring with better data and granting the recipient some agency over their score is commendable, these half measures result in a score that raises more issues than it solves.

The final potential potential disruptors to the current creditworthiness system are creditworthiness startups which prioritize the rating recipient. Though few in number these entrants’ innovations are major. Most notable is the startup CreditKudos in the United Kingdom. Like the bureaus, this startup relies on consumer consent and open banking to access rating recipient financial records. However, unlike the bureaus these startups rely on only the data consumers share, legitimizing themselves to the recipient. Further, these scoring systems rely on a broader scope of financial accounts, meaning richer potential insights. However, this model is still vulnerable to traditional failures. Most notably, these solutions continue to rely upon the traditional scope and mechanisms of the legacy bureaus. Requestors are the ones driving sharing and requesting of simplified one-size-fits-all scores, and only for traditional lending decisions. Recipients are unable to simply have their scores calculated. Furthermore, recipients have little input into how their ratings are calculated and presented. Financial aberrations without context are much more concerning than those with. Finally, such systems fail to provide a comprehensive view by limiting inputs to only certain types of input data provided by the recipient. Not only does this cause issues when relevant accounts are excluded, but it also precludes creditor-reported information from being incorporated (e.g. defaulted on a debt).

Economic reputation has suffered poor creditworthiness systems for more than fifty years, and these attempts offer welcome new thinking. However none address all the issues of legacy systems, and introduce issues of their own. This is a shame, as an ideal creditworthiness system is possible and worth pursuing.

doing it right

“Character is like a tree and reputation like its shadow. The shadow is what we think of it; the tree is the real thing.”

- Abraham Lincoln

Building the ideal creditworthiness system is possible. Thanks to modern technology, the pieces just need to be put together.

To start, the ideal creditworthiness system should portray economic reputation as accurately as possible in order to best reflect an entity’s true character. This necessitates a paradigm shift from treating creditworthiness as a simple score but rather as a passport of one’s financial identity. Existing systems fail to recognize our capacity for multiple characters / identities depending upon the perspective - a business is successful in one context, a flop in another. The ideal creditworthiness system must present not only the most accurate, but also the most relevant assessment of a given entity to the requestor.

The rating approach should be determined by explicitly defining the interaction to be facilitated by the assessment. A car loan application could encompass a potential lendee’s loan repayments and motivations for purchasing a car, while a commercial contract could consider patterns in a company’s working capital. There is no need to integrate non-relevant and overly-intrusive information into a rating.

All economic entities should be free to share or not share their creditworthiness as they see fit, and access to creditworthiness assessments must only be provided upon the consent of those they represent. Recipients must also be able to control what information is represented, albeit with clear annotations that not all information is portrayed. Such recipient provided ratings must be verifiable, objective, accurate, and immune to tampering. Both parties should be incentivized to share information about themselves in order to establish trust, and that starts with knowing consent and the counterparty’s acknowledgement thereof.

Accurate assessments require comprehensive data. Nothing is more predictive of future actions than past behavior. A new system should leverage open banking and user consent to pull as much information as possible to predict future behavior. Automated checks should look for, note, and press for filling in missing information. Meanwhile, third parties should be able to independently submit verified notes on a given entity to ensure bad behavior is punished. Creditors and relevant third-parties must have recourse to influence recipient reputations. A fair system is a trustworthy one.

Assessment algorithms should be dynamic and output purely quantitative information for decision making. Specific and predictive scores provide far more value than abstract ratings (e.g. AAB?). Scoring should be designed and clearly positioned as augmenting, rather than replacing the requestor’s decision making process. That’s not to say automated decision making be rendered impossible, only that requestors be given the requisite data points to make informed decisions in a programmatic way.

Ratings must also be fair and objective as well as subject to change. Ratings should account for extraneous, societal influences to avoid perpetuating unfair prejudices. Scoring algorithms should be transparent, open source, and verifiable by anyone. Recipients and requestors should retain the right to present and request, respectively, the scores they so choose. Third parties should be incentivized to develop new and refine existing scoring models, and the system able to integrate them easily.

One overall set of scoring principles should cover both individuals and organizations. Simplicity begets understanding begets trust.

The creditworthiness system should look beyond scores themselves to provide general context on the rating recipient. For instance, benchmarking a recipient to a relevant peer group would provide immeasurable value to requestors, as well as inform recipients. An intelligent system would also allow for benchmarking versus a variety of peer sets, in acknowledgement of the multi-facted nature of both individuals and organizations. ‘Smart’ benchmarking lends nuance to creditworthiness which does not currently exist.

Scoring should also provide unique context, and allow for change. A lapse in past judgement, since atoned, should not preclude future opportunity. A reputation should reflect character - not entrap it. Allowing recipients to provide context - whether or not the requestor would use it - would enable a fairer system. Furthermore, such a system should identify when an entity’s behavior has fundamentally changed, versus an aberration. A single poor decision should not be treated as increasingly careless behavior. Likewise, deceptive measures to improve credit ought to be identified and considered for what they are.

A creditworthiness system should be dynamic and reflect real time changes. This encourages fairness for both requestors and recipients as well as improves rating accuracy. Furthermore, ratings should leverage machine learning to look forward and project reasonable estimates of future behavior. Obviously not in a deterministic manner, but to provide requestors with educated guesses on the near and mid term, as well as alerts to recipients on whether to course correct their financial behavior.

The system’s business model should encompass recipients in addition to requestors. Agency over one’s own creditworthiness should come with a cost. Recipients benefit from showcasing and sharing their scores in modern society, and should share the costs associated with doing so. That said, participants within an interaction should be free to determine how costs are distributed amongst themselves.

Putting these elements together should bring us closer to a creditworthiness system wherein economic reputation more closely reflects character. More than that, such a system would be fairer for both requestors and recipients than the one today.

redefining reputation

As indirect relationships overtake direct ones, the need for a more equitable, transparent, and relevant creditworthiness system only grows more acute. I am convinced a new creditworthiness paradigm is possible, and with it, tremendous opportunity. Financial identity could supplement, or even replace official ones. After all, what is more authentic and irreplicable than one’s financial behavior? Governed by recipient consent, such a system would be far more relevant to the myriad of use cases credit ratings are applied to today, like background checks, various forms of underwriting, real estate transactions, and more.

Who will take up this mantle? Governments, industry, or something in-between? I believe the best solution will be industry-led. Governments can be too overbearing (e.g. China), too lax (e.g. the U.S. and how the bureaus have a government sanctioned oligopoly), or simply too slow to implement and innovate. Building trust is a value-creating service which can bear a margin.

The world deserves a better method of building trust. Offering a platform for individuals and entities to manage their reputation is a great place to start.

I welcome your feedback. Please don’t hesitate to reach out through the contact section of the website if you would like to discuss, comment, or have any suggested edits.

[1] It is worth noting this builds off the system proposed by Malcom Thaler in his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow”. Direct reputations are System 1, while indirect reputations are built by System 2.

[2] For US residents - this is why your score varies by bureau. The same algorithm is used, but each of the major bureaus have different information on you. Thus, slightly different scores.