phase change | the rise of real time payments: part II

This is the second of a three-part series on the novel payments technology “Real Time Payments” and how they promise to upend finance as we know it. In Part I we established a baseline understanding of today’s dominant payments networks, their basic workings, relative strengths and weaknesses and so on. With this context we are now prepared to dive into what Real Time Payments (RTP) are and why they are so disruptive to the status quo.

We left off concluding several dominant payment channels have emerged to meet market needs, but no single payment channel does so particularly well, much less offer a universal solution. In this essay we will review how RTP promises to supersede the performance of all existing payment channels and cater to nearly every market need, into perpetuity. This is a bold claim and we will establish it by reviewing each of its attributes in turn.

But first, let’s define RTP. Like any new or potentially groundbreaking technology, RTP is surrounded by noise. In this series we’re defining Real Time Payments as a new payments network characterized by the attributes described below. RTP is not an extension of existing systems. The names “Fast-ACH”, “ACH Plus”, “Faster Payments”, and “Instant Payments” are occasionally used in industry and media but are generally less accurate and may refer to proprietary systems, caveat emptor. Finally, it is worth noting The Clearing House firm in the US is attempting to brand the term “RTP Network” which causes further confusion.

what are RTP networks?

RTP Networks are conceptually simple - digital ecosystems providing secure, instantaneous, dynamic, and data-rich messaging at scale. The similarity to other modern messaging systems is no coincidence. RTP is not built on any specially invented technologies, rather, it simply represents the best modern Information Technology has to offer. What sets RTP apart from the legacy networks covered in Part I is that its infrastructure is built by the right parties at the right time. All other major payment rails (other than Alternative Payment Networks) were built decades ago using primitive technological systems and processes. RTP has instead been built on modern, forward facing infrastructure by finance professionals.

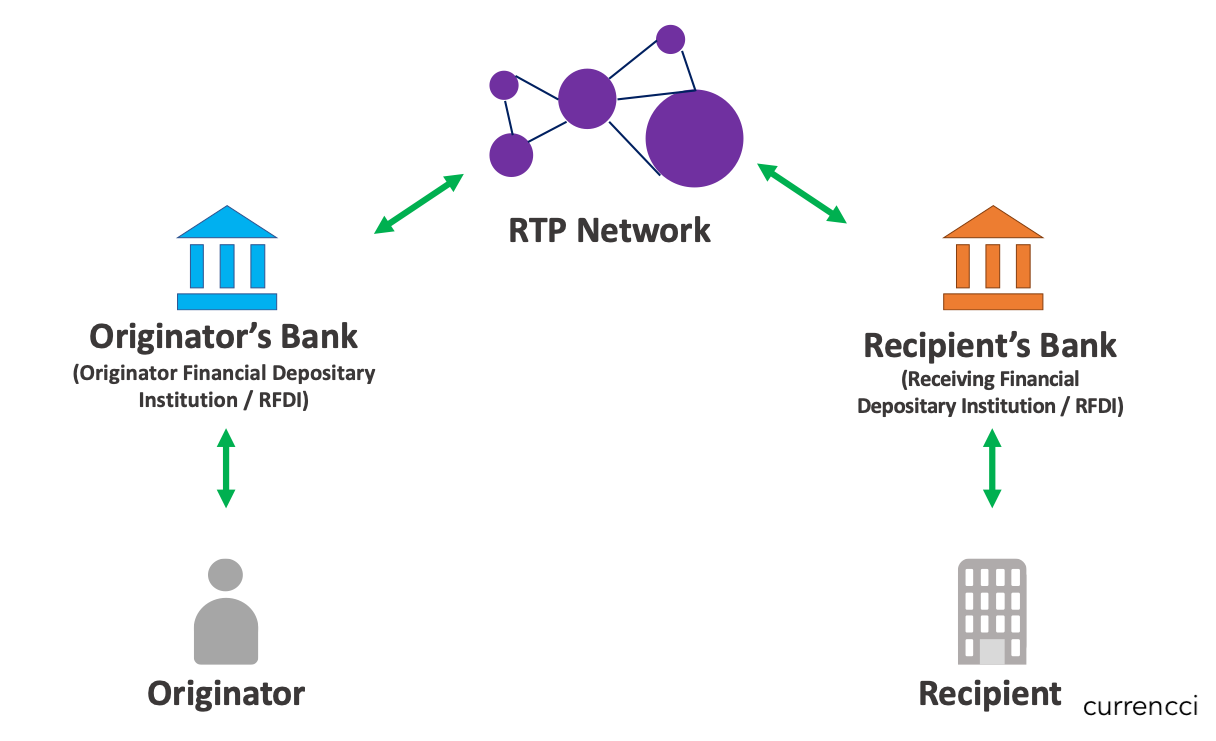

So what is a Real Time Payment? Consider the diagram below, which provides a simplified transaction flow. Value and remittance information is instantaneously transferred from an originator’s account at their financial institution to a recipient’s account at their financial institution. Unique from other Networks, RTP allows every component of a transaction - the payment initiation, value, and contextual data - to be passed along simultaneously in one ‘message.’ Further, RTP allows for customization of each component, meaning as much value and data can be transmitted back and forth between parties as desired (or as limited by the RTP network operator).

Figure 1: The basic architecture of the RTP Network.

Figure 1: The basic architecture of the RTP Network.

Just this overview provides ample food for thought and those inclined may skip ahead to the Part III which offers thoughts on the implications of RTP. However, the nuances complete the perspective, and with these in mind we can better review RTP’s broader meaning.

speed

The most obvious characteristic of RTP is how transactions take place immediately. At root of this functionality is “Real Time Gross Settlement,” or RTGS, which enables value transfer between accounts the instant the payment is submitted to the network operator (i.e. on a continuous basis). This is in contrast to most existing systems, like the ACH networks, which ‘settle’ transactions in bulk at set intervals. Further, RTP Networks are live 24 hours a day, seven days a week, unlike some legacy systems which are periodically shut. For all intents and purposes, RTP offers instant payments at any time between two bank accounts.

It is worth noting the payment speed is unaffected by the transaction value. RTP Networks theoretically allow for payments of unlimited amounts (though all current implementations have caps as the industry grows familiar with the systems). Whether $5 or $5,000,000, RTP ensures consistent, timely delivery.

Immediacy lends payment originators a valuable new tool. The immediacy and certainty of payment enables originators to send payments at exact times under ideal circumstances. For instance, an originator could program for paying a vendor only once certain conditions are met. Even for the most unsophisticated originators it is easy to imagine basic rules becoming commonplace, for instance not sending out payments which may ‘bounce’ an account, or setting recurring payments to automatically occur in a manner which maximizes available cash on hand.

RTP’s always-on nature follows a standard pioneered by the Card Networks and cements the payment industry’s long transition to uninterrupted service. All payment participant types - consumers, businesses, and even governments - now expect 24/7 payments and RTP’s ability to facilitate large and complex transactions at all times sets the bar high for the legacy networks.

risk

Immediacy, however, is a double-edged sword as RTP’s instant payments introduce higher general risk. As I’ve mentioned in an earlier essay, the faster the payment the higher the risk. Less time to think, verify, and approve means more chance to make mistakes, or even worse, for nefarious actors to conduct irreparable harm. RTP’s immediate transfer times raise these stakes considerably, especially considering how high payment values can grow over the RTP Network. That said, immediate payments reduce the transit time of sensitive information and make the process less susceptible to interception. Further, numerous security features (covered below) are used to prevent and discourage criminal activity.

From an accounting standpoint RTP’s risk comes out as a wash with payment certainty transitioning from the originator to the recipient. On one hand, immediate payments eliminate the working capital benefit originators’ have enjoyed with legacy payment channels - no longer can an originating firm (or individual!) leverage the extra few days of liquidity once ‘a check is in the mail’ or a payment is ‘out for processing’. This ‘extra’ time reduced the originator’s financial risk as it provided valuable time to validate the delivered service or goods, or increase the certainty of such. Meanwhile, with RTP, recipients obtain their funds immediately - eliminating the uncertainty of whether enough funds will be available by the time the transaction occurs.

Fortunately for RTP Networks, the above risks may be rebalanced between participants as needed, reduced, or even eliminated through complementary services built atop the network. Discussed further in the later adaptability section, RTP Networks offer a foundation for third party services to build upon. Given payment risk tolerance varies by participant and transaction type, third party services may eventually offer niche mechanisms to spread this risk as needed.

Risk is an inherent aspect of any payment. What sets RTP apart from legacy networks is not that the risk is inherently lower, but rather it can be distributed as much as needed.

data

Real Time Payments is somewhat a misnomer - the payment speed of RTP Networks is far less important than the data transmitted. Payments have in fact historically consisted of two distinct ‘messages’ transmitted between the originator and recipient: (i) the payment’s value itself; and, (ii) the contextual ”remittance” information supporting the payment, consisting of everything from a formal invoice to an email to a verbal exchange. The original sin of the legacy payment systems has been the separation of these communications and how they’ve focused on value transfers while ignoring remittance information (e.g. your paper receipt when paying with cash or card at a restaurant). While that may have been appropriate for earlier more technologically constrained eras, enriched data is mandatory as payments, business, and society have grown more sophisticated.

RTP’s data transmission is nuanced and consists of three main elements: (i) its content; (ii) its interoperability; and, (iii) its expandability. The engine powering them all is ISO 20022, a ‘global and open standard for information exchange’ [1]. First developed in 2000 by the SWIFT [2] organization and now owned by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), the language has been continuously updated since to provide a universal digital language for business. Reviewing each of RTP’s / ISO 20022’s main elements in turn reveals how game-changing its data transmission really is.

ISO 20022 allows nearly unlimited data transmission between originator and recipient. The easiest analogy is email. Email users all employ the same basic set of fields as a medium to send each other messages with nearly limitless variability. One email may be sent to dozens of strangers at different providers (e.g. @columbia.edu, @hotmail.com, etc.) containing poetry with unique formatting, while another may be between two close friends on the same network and contain a photo attachment. In the same way, RTP offers an extensible set of fields that can be filled with nearly limitless content. An RTP payment may contain a full receipt for a service or even invoice accompanied by a quote from a contract. RTP thus provides participants, regulators, accounting systems, and more with as much immediate and contextual information as necessary.

Beyond just moving data, ISO 20022 provides a framework for how to best structure it. Returning to our email analogy, emails use a common standard agreed upon by participants to share messages. Central to this system are the set fields which are used to transmit information. The overall structure of fields is referred to as the model (e.g. certain fields in one configuration make an email, while in another make a calendar invite), the technical language underpinning the fields and framework is the syntax (e.g. the ‘Subject:’ field and its placement relative to other fields), and the meaning of the content populating each field is known as the semantics (e.g. the ‘To:’ field announces the recipient). Like email, ISO 20022 uses syntax to arrange fields into various models (or payment message types), only with far more complexity than email. ISO 20022 offers hundreds of message types and fields - more of which are introduced regularly - as well as allows participants to design and build their own. Further, ISO 20022 makes itself accessible to all through leveraging the common technical formats XML and ASN.1 as its underpinning syntax. Through this well-built foundation, ISO 20022 effectively provides a universal language for payment messages.

This universality offers not only future-facing elegance, but also here-in-the-present practicality by enabling interoperability with legacy payment systems. Models and fields used by legacy systems can be mapped to those of ISO 20022 and back again, meaning old systems can connect to new ones, or even two previously incompatible systems to one another. Backwards compatibility allows RTP to sidestep the financial industry’s natural stubbornness towards adopting new technologies, while offering those early adopters the opportunity to innovate and surpass their rivals.

Most compelling is ISO 20022’s expandability. As mentioned in International Organization for Standardization’s (ISO) brief guide:

_ISO 20022 is a business standard; its principal focus is on the content of the dictionary, rather than the technicalities of how data is exchanged[3].” Finance and payments are the most basic form of interaction in business, and RTP offers to streamline these communications. Beyond this, RTP through ISO 20022 aims to provide a rich and evolving language for all business interactions. For instance, payment messages could one day be supplemented by additional non-payment communications like receipt confirmations, delivery updates, contracts, and more. Looking forward, RTP is building a worldwide network for securely transmitting human and / or machine-readable messages between everyone and everything.

The opportunity presented by RTP’s data capabilities for innovation, collaboration, and new business models is boundless.

direction

In Part I we covered how nearly all payment systems are uni-directional (except ACH Networks). This means payments could be initiated by either the originator or the recipient, but not both. For instance, in a cash payment the originator decides when the money will be transferred, and how, whereas in card payments the recipient enjoys this role. As one would expect, each variation has its pluses and minuses.

RTP systems stand out, like ACH networks, in allowing both originators and recipients to initiate payments.

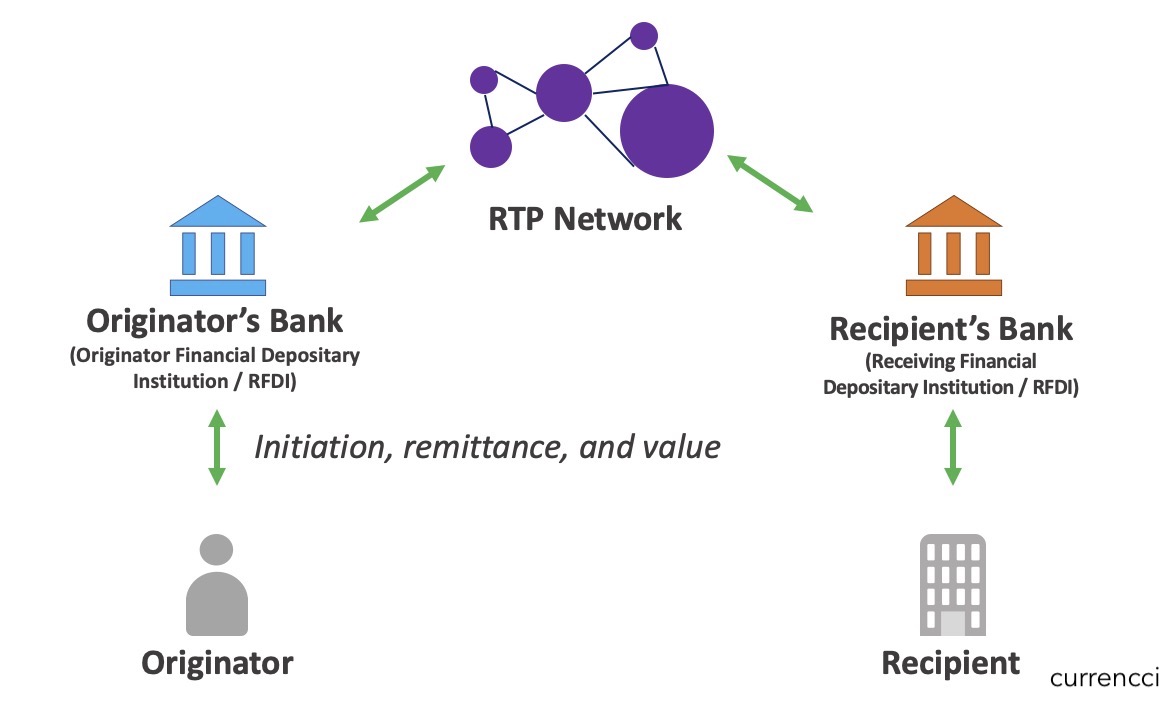

It is simple for originators to initiate payments on RTP Networks. An originator sends a payment message, containing relevant remittance information to the recipient. This information could be supplemented as much as the originator would like using the aforementioned data expandability provided by ISO 20022. An advantage over some legacy systems, the immediate nature of the payment provides extreme control over when and how the payment value is sent. Accounts Payable departments everywhere can enjoy added control over working capital and cash flow.

Figure 2: A basic ‘push’ payment across the RTP Network.

Figure 2: A basic ‘push’ payment across the RTP Network.

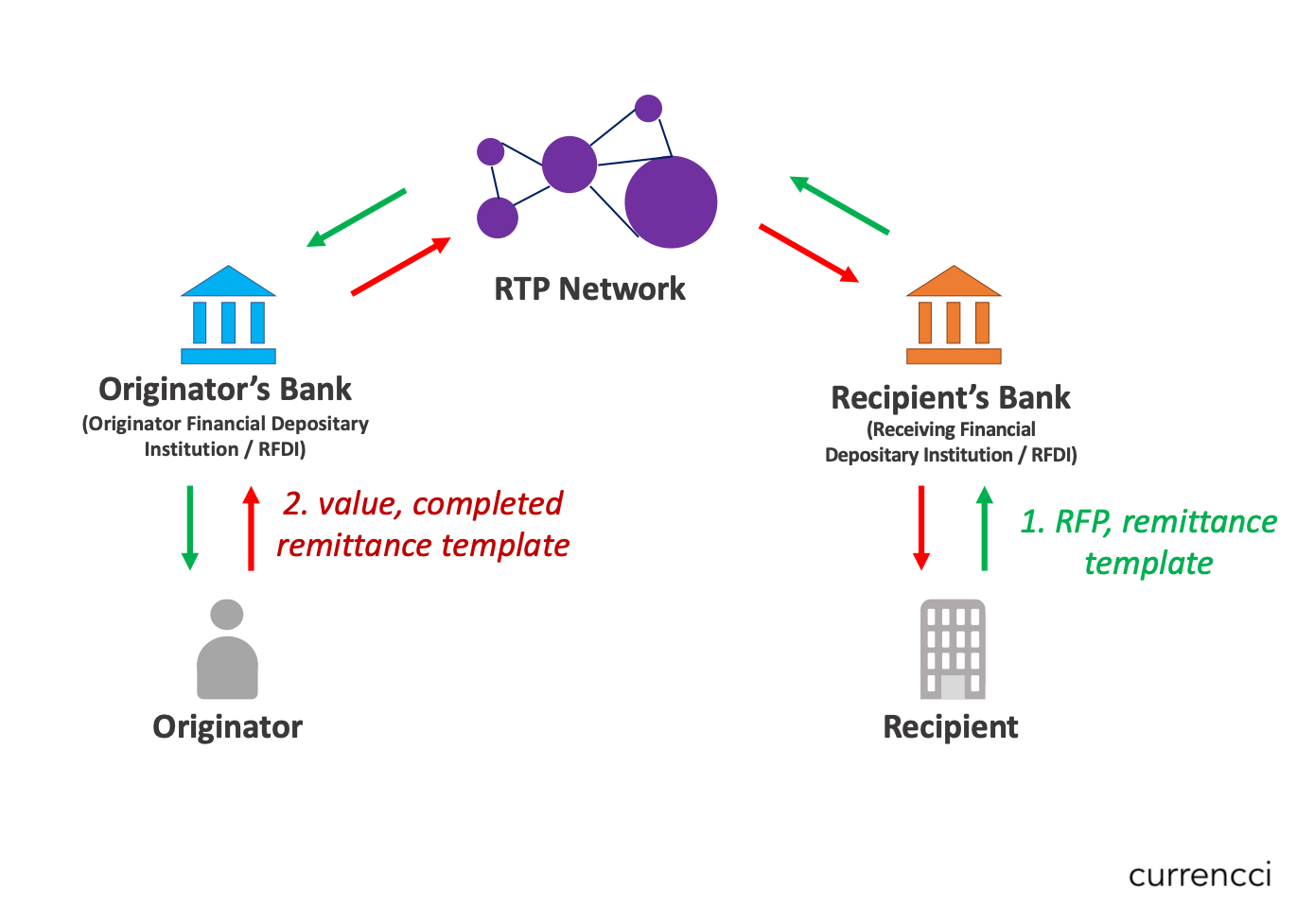

Recipients enjoy a nearly equally easy process to initiate payments on RTP Networks. To do so, a recipient sends out a “Request for Payment” or RFP to the originator. Through ISO 20022, the RFP may contain not only the required amount, but also various remittance information in a specific format. Once received, the originator reviews the RFP, accepts it, and the payment is processed. It is worth noting that RFPs with RTP Networks are unlike ‘pull’ payments across ACH networks, which empower recipients to deduct funds straight from an originator’s account. RFPs cannot unilaterally ‘pull’ value from an originator. Rather, the originator must validate and verify the request.

Figure 3: The general flow of an RFP payment across the RTP Network.

Figure 3: The general flow of an RFP payment across the RTP Network.

The RFP is a tremendous advancement for payments. Recipients - Accounts Receivable in commercial settings - have long been ignored by the payments industry, and with good reason. In solving for the ‘chicken and egg’ issue of multi-sided platforms (business models bringing together two populations - think how jobs boards need both applicants and posters to work [4]), payment platforms typically favor the originators to entice users to the service. This is because recipients are generally eager to obtain the originator’s value and typically willing to accept whatever payment method the originator prefers. The end result is a litany of recipient annoyances including: higher payment fees, forgotten or intentionally missed originator payments, and a lack of remittance information. This last point is particularly important - as businesses have scaled in complexity, pairing incoming payments across a variety of rails with remittance information has grown exceptionally difficult and expensive. With RFP, recipients are able to dictate the terms of payment, from the amount of value to the requested remittance information. Were this solution ubiquitously in place today, it would undoubtedly save billions of dollars of value in back-office operational expenses for firms everywhere.

Empowering both originators and recipients makes for the most egalitarian and universally attractive payment channel ever created. This flexibility granted to payment participants is unprecedented and unmatched by legacy payment channels.

irrevocability

Despite its central importance to all payments, certainty has been long neglected by major payment channels. ACH Systems, Card Networks, Wires and Alternative Payment Networks all tote mechanisms to cancel or even rescind payments. Up until now, only cash has offered indisputable finality to its users. RTP Networks again buck the trend of legacy systems by introducing finality, termed irrevocability, to electronic payments.

The concept of irrevocable payments tends to induce a knee-jerk reaction of concern, layered with skepticism. Everyone reading this can easily recall making payment mistakes - sending a transfer to the wrong recipient, or giving card information to a suspicious retailer. The ability to revoke or modify those payments saves us from losing our funds. The rules and governance surrounding this revocability lend us both comfort and confidence in using the system. How could a system without these guardrails possibly be appealing?

The secret of revocability is the simplicity. Once a payment is made, that’s it. The value and message details are transmitted from the originator to the recipient. The implications are more nuanced. Most important, this lends recipients unprecedented certainty. No longer does a vendor need to worry whether or not a check will bounce, or a card chargeback initiated. Managing and predicting cash flows grows far easier for recipients with RTP. Second, this shifts dispute management between originators and recipients from the payment network to the legal environment encompassing the originator-recipient relationship. This dramatically reduces costs for the payment network, while simultaneously providing an egalitarian environment for payment participants. Third, irrevocability encourages innovation to mitigate the risk or erroneous or malicious payments. It is easy to imagine firms emerging to offer value added services in validating recipients, or providing payment ‘insurance’.

Legacy payment networks have imposed Byzantine rules to enable payment revocability in exchange for drastically reduced payment certainty. By re-introducing irrevocability to modern payments RTP Networks offer a simple, egalitarian, and dependable payment channel.

cost

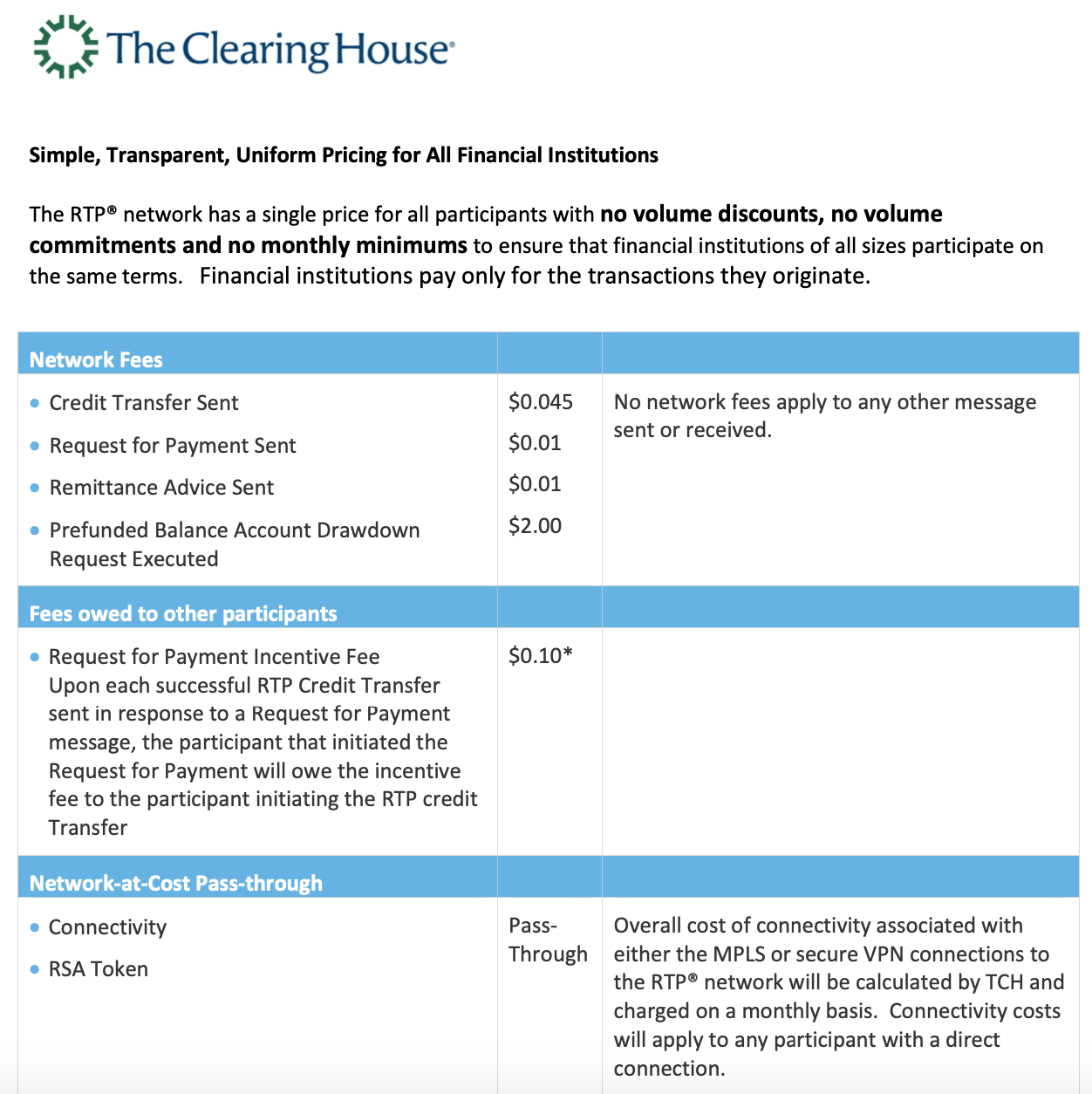

Real Time Payments are cheap. Unlike Legacy payment networks which either explicitly (e.g. Card Networks, Wires) or implicitly (e.g. Cash) impose steep costs, RTP Networks offer transparent, low pricing. These traits together are remarkable in an industry known for arcane, complex, and often times confusing pricing. For instance, consider the pricing sheet for the US RTP Network offered by The Clearing House organization, representative of the major RTP Networks:

Figure 4: The entire pricing sheet for messages over TCH’s United States RTP Network.

Figure 4: The entire pricing sheet for messages over TCH’s United States RTP Network.

Fees are fixed, universal, and low. Certain messages sent across the RTP Network to better its services - in this case specifically around operations and security - are free. For comparison, the major Card Network Visa has 24 pages of documentation just on fees for small businesses in the United States. One doesn’t even need to read the documentation to know the pricing within is expensive, variable, and opaque.

Industry-best pricing paired with industry-best features unlocks tremendous opportunity for innovation. High per-transaction costs of legacy networks encouraged bulk payments in place of ad-hoc ones, delaying payments and limiting available remittance information. RTP Networks obliterate this bottleneck by lowering per-transaction costs by orders of magnitude. Now, originators and recipients are empowered to send extremely high volumes of payments at moderate expense. The market is now able of re-equalize the volume and rate of payments to meet this lower pricing. It is easy to imagine larger payments being broken down into multiple, lower value transactions in order to minimize risk and maximize information transmitted. A monthly rent payment could be broken into weekly installments, or a car payment to thousands of miles driven.

These low end-user costs do come with a steep up-front cost for providers. Like any new information technology, RTP saddles its bank and operator providers with substantial implementation costs and complexity. These costs will slow implementation in the near-term, but not halt it. International precedents and domestic government competition when applicable will prevent these costs from being offset by higher fees. Instead, implementation costs will be made up over the long term as well as through any additional services providers can invent. From an ongoing operational perspective, RTP provider costs should decrease quickly and persist at low rates.

While RTP’s features make it competitive with legacy payment networks, its pricing makes it truly disruptive. RTP Networks provide the industry’s most advanced capabilities at the cheapest price. It is only a matter of time before this payment method becomes dominant.

ubiquity

Imagine if every merchant used its own payment system with unique rules. It would be a mess! Successful payment channels avoid confusion by offering ubiquity. This means the platform: (i) has a large number of participants; (ii) allows new participants to easily join and use the service; and (iii) is available when and where needed. In other words, ubiquity means everyone can use it to send and receive payments at any time. Ubiquity provides legacy payment networks usefulness and longevity. Likewise, new entrants face significant barriers to entry as they must attract participants from legacy platforms as well build capacity to support payments when and where desired.

Despite these hurdles RTP Networks are positioned to quickly reach ubiquity. Key is RTP’s inherent nationalistic centralization. In most markets the Central Bank operates the country’s RTP Network. As the Central Bank already has relationships with all the private banks within the market, it is straightforward to onboard each to the RTP Network. With that, all consumers and organizations gain access to the system through existing banking relationships. Trying and switching to RTP payments is frictionless for participants as no significant behavioral change is necessary.

It must be noted that because of this national, centralized structure, RTP Networks’ ubiquity is limited to their own market. The UK’s RTP Network only operates within the UK, while Japan’s only functions within Japan. As of yet Central Banks are leery to expose their relatively new systems to external jurisdictions, and thus RTP Networks are currently unable to facilitate cross border payments.

Egalitarian government operation of an RTP Network is essential to its ubiquity. Governments are committed to equal access, meaning both large and small banks face equal requirements to join and participate on the network. Government operation also means pricing is kept at break-even levels.

In fact, it appears markets have little appetite for privately-run national RTP Networks. The United States Federal Reserve decided to wait for an ‘industry-led’ RTP Network to develop rather than develop its own in order to avoid ‘big government’. After waiting nearly a decade - and allowing the United States financial system to fall behind as most other modern markets developed their own RTP Networks - The Clearing House (TCH) announced it was releasing its own RTP Network. The trouble is TCH is a private company owned by major US banks, and small banks around the country immediately realized outsourcing a core function to their competitors was poor business. Legislators were petitioned, and ultimately the Federal Reserve relented in building its own system.

RTP Networks are not yet ubiquitous but are positioned to quickly permeate their market’s financial networks, much to the chagrin of legacy payment networks who built up their presence over decades. The major outstanding question for such systems looking forward is how will they be joined internationally, and whether this will be through a private or regulatory body like the United Nations or World Bank.

compatibility

‘Multi-sided platform’ business models rely on bringing and keeping participants on their ecosystems. For instance, the more consumers using credit cards draws more merchants, which draws more consumers and so on. The opposite is also true. One participant group leaving the platform can cause a vicious cycle wherein all users abandon the platform. If no merchants accepted cards, nobody would use them.

Many platforms counter this threat by imposing ‘Leaving Penalties.’ Well implemented Leaving Penalties foster healthy multi-sided platforms by ensuring an engaged participant population. Consider a mall imposing a parking fee for consumers who visit but don’t buy something. Poorly implemented Leaving Penalties however can cause considerable harm, from stifling innovation to actively exploiting participants. The same mall may decide to impose a high ‘minimum transaction size’ limit for parking validation, forcing consumers to spend more than they would like when visiting the mall. Ultimately, a poorly balanced Leaving Penalty can destroy a platform once participants realize the cost of staying on the platform is greater than its value.

Leaving Penalties for Payment Networks center on penalizing value transfers out of the channel. Difficult value extraction keeps funds on the network and flowing between participants. For example, the Alternative Payment Network Alipay charges a 0.1% fee for all withdrawals over 20,000 Yuan (~$3,000 USD). This penalty ensures users realize more value by using and keeping their funds on the channel. While beneficial in the near-term by keeping participants engaged, I believe Leaving Penalties irreparably harm payment networks over the long term. As time goes on, participants may feel trapped within a network and grow resentful of its seemingly ‘anti-participant’ rules. Money is a touchy subject, where perception can matter more than reality. Regardless of whether regulators force change, voluntary change occurs, or Leaving Penalties remain, participant trust and network preference decreases with their presence.

RTP Networks lead the industry with compatibility by making it frictionless to transfer value into and out of the channel. This strategy effectively passes along the Leaving Penalty question and corresponding participant focus on the financial institutions who provide access to the RTP Network, rather than the channel itself. As such, RTP Networks enjoy less regulatory scrutiny and participant ire. Like all good utilities, RTP functionality fades into the background and enables participants to pursue their real goals, rather than serving as a distraction or eliciting unwanted scrutiny.

adaptability

Just as important as its capabilities is RTP’s adaptability to changing participant and technological requirements. In Part I we reviewed how all legacy payment networks other than the Alternative Payment Networks are encumbered by outdated infrastructure, operations, and processes which make them incapable of meeting modern participant needs.

RTP Networks are different. Their underlying technical and business architecture is built on the premise of ongoing adaptation to market needs. Technically, RTP Networks are (generally) built using modern programming languages, architectures, and hardware. Functionally, the network leverages the aforementioned ISO 20022 standard that is quickly expandable to shifting participant needs. Practically, both banks and participants can easily join and use RTP Networks to originate and receive payments. Together these attributes make for the financial industry’s most forward facing payment rail.

Beyond the infrastructure itself, RTP enables further adaptability by enabling third party providers to build atop itself. RTP’s simple, certain, and modern capabilities lend themselves to innovators looking to leverage or tweak the payment channel to meet specific needs. This could range from proprietary governance frameworks for mitigating risk to accounting software to effectively parsing and sending extended remittance data to trading partners. Like any good software platform (i.e. the Apple iOS App Store) RTP Networks foster an environment of innovation and creativity which increases the overall value and capability of the channel.

As payment needs and regulatory environments continue to evolve, RTP’s adaptability will provide a strong advantage over legacy payment networks. As a result, the payment industry’s innovation bottleneck is now set to shift from the payments networks themselves to its providers and participants. This creativity and potential new functionality will only further enhance RTP and heighten its advantage over the legacy payments networks.

RTP in review

Putting RTP’s attributes together reveals just how disruptive it is to the payments ecosystem. Its simple business model combined with its modern technological infrastructure puts it leaps and bounds beyond all other existing major payment channels.

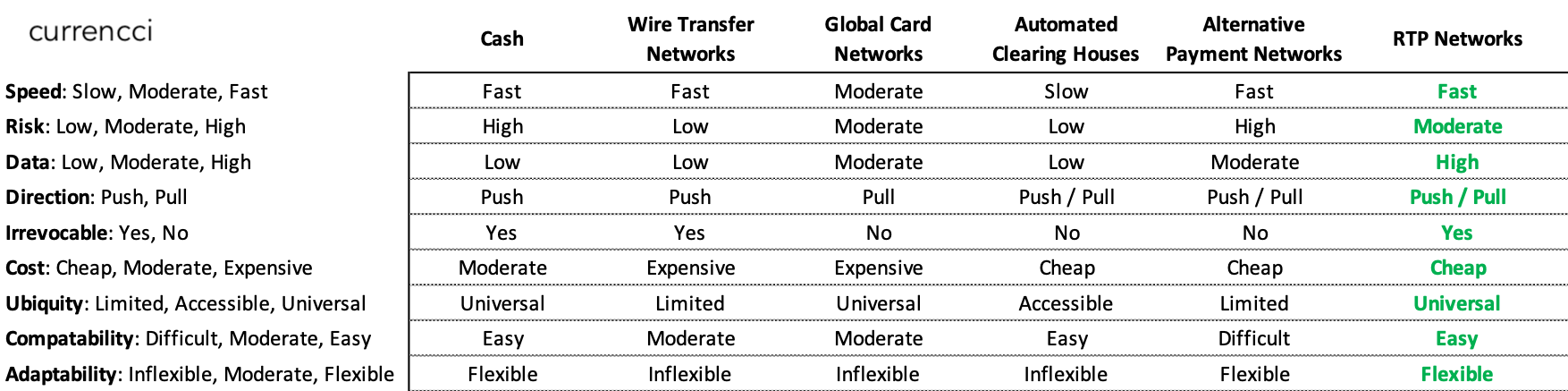

Table 1: RTP Network attributes relative to legacy payment networks.

RTP networks today

Though today’s RTP Networks are still new, they are poised for rapid growth worldwide. The difficult steps of building the core business, regulatory, and technical requirements are now complete. Technology and governing agencies have advanced enough to support the high demands of supporting RTP Networks, while participant needs are growing more acute daily. With this groundwork in place all that is now needed for growth is to implement and open up the systems to mass end-users.

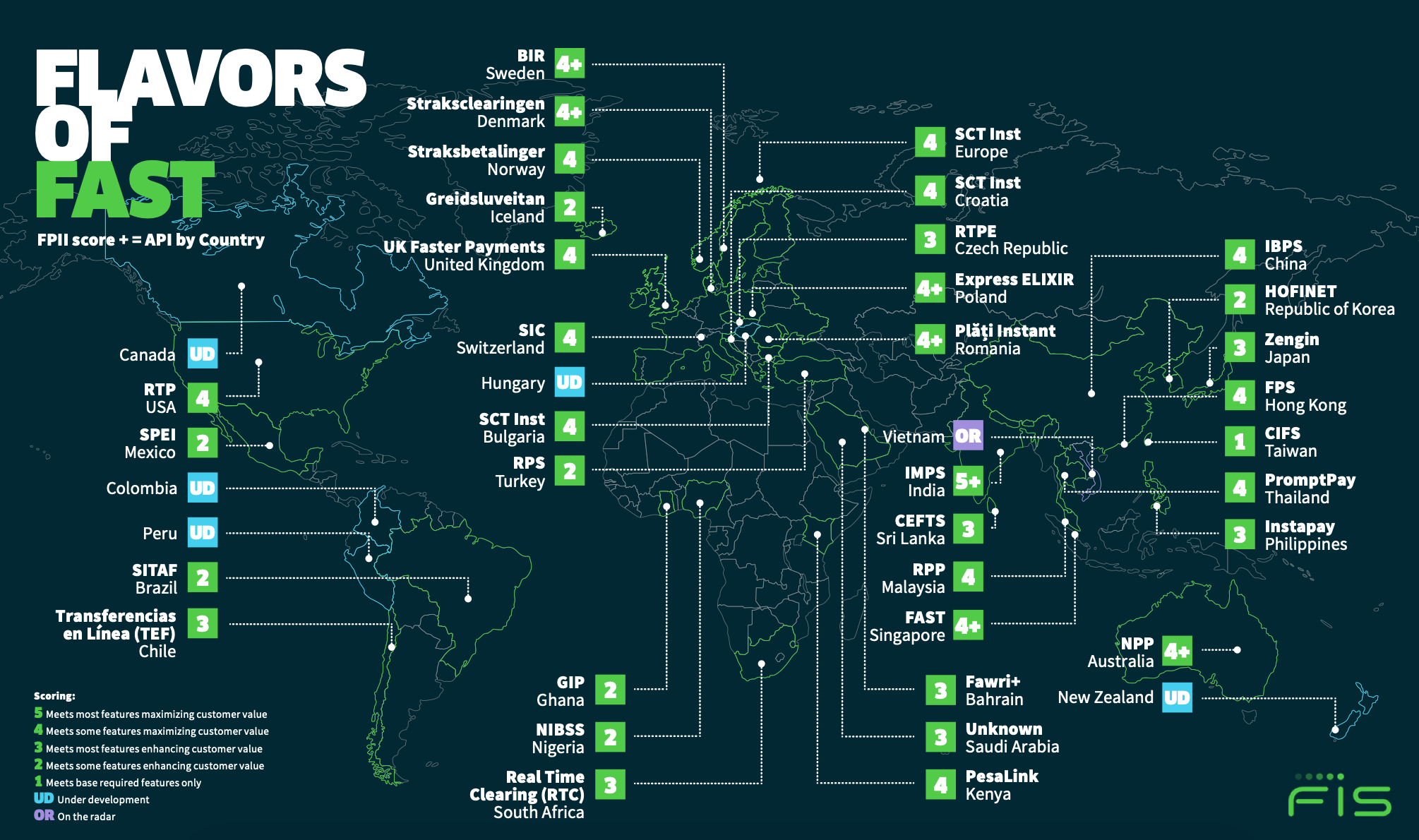

Figure 5: Map of RTP Networks worldwide and their various phases of implementation. Source.

Figure 5: Map of RTP Networks worldwide and their various phases of implementation. Source.

Implementation can take three forms.

First is through government mandate wherein regulatory agencies directly establish and operate the RTP Network. This model ensures universal access across a market, and at-cost operation. Operation is transparent, yet potentially slow in adapting to shifting market needs. Some examples are the SPEI RTP system in Mexico or the UPI RTP Network in India.

Second is implementation through private industry. This is where private organizations develop RTP Networks in lieu of or in competition with the local government. While offering likely greater adaptability to evolving market conditions, by their very nature as private organizations these systems are more vulnerable to price increases or less egalitarian customer servicing. The Clearing House’s RTP Network in the United States is a good example of a private network.

The final and third form of implementation is government operation of a privately built and maintained system. For instance, a government may license the software of a private organization for use within the market. This allows governments to focus on their expertise - governing - while outsourcing the technical difficulties of designing and building an RTP Network from scratch. Thailand uses such a model.

A balance between the three is ideal. A secure and efficient financial system is essential to any functioning society, and the modern economy demands safe, cheap, electronic payments. Digital payments are transitioning from a specialized service to a commoditized utility and should be provided in some form by the government. There will always be room for specialized payment channels like the Card Networks, but they must actively contribute a differentiated service in order to justify their fees. Facilitating online payments between bank accounts is no longer unique in today’s digital environment.

The RTP business model also naturally lends itself to government operation. Private RTP networks are incentivized to maximize profit whereas public RTP networks measure success through use. Strategies to maximize engagement for a profit-driven private platform all fail when competing with a public alternative. Consider interoperability, a key consideration for many end-users. Private networks tend towards proprietary features and closed ecosystems while public networks favor universal standardization. Over the long term, as international systems grow increasingly interconnected, I suspect RTP systems will naturally tend towards government operated implementations.

RTP’s path to market dominance will come in stages. Like any successful business or technology, RTP has started by solving niche needs before going mainstream. Though the stages will vary across markets, the general approach is as follows. First, RTP’s introduction has mainly begun by facilitating person-to-person (P2P) transactions. As simple, low-value transactions, these present few technical challenges and offer an easy path towards successful deployment in-market. In the second implementation stage business-to-business (B2B) payments are introduced. These are far more complicated than P2P payments and are launched in an extremely measured manner. This allows the system to build out capabilities in supporting larger value and more data-rich payment messages. The final implementation stages is in mass consumer-to-business (C2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) payments, wherein the network opens up to general consumer purchasing behavior. At this point the system has essentially reached full ubiquity.

RTP Networks are in various implementation states worldwide and none as of yet have realized their full potential market penetration. Only growth lies ahead. RTP surpasses incumbent payment networks in nearly every category and its adaptable design will ensure it continues to evolve to better solve market needs. It is worth mentioning their centralized nature - in most cases they are highly regulated and endorsed if not run by the market’s central government - which allows RTP Networks to quickly scale. RTP providers typically have pre-existing relationships with most financial institutions within a market, and on-boarding can be accomplished quickly with support of third party facilitators. The network’s value grows as banks join, further accelerating growth. Ultimately, bank participation translates directly into access for consumers and businesses. This isn’t just a nice theory - TCH had 19 major U.S. banks in its RTP network in January 2020, 30 in June, and more than 60 by August. It won’t take long for most businesses and individuals to have access to an RTP method of payment.

But what will this mean? I believe the financial industry over the next five to ten years will be completely reshaped by RTP’s rise. In the last and final Part III of this series, I will explore how RTP may do so and the potential implications on the payments industry, finance, and society at large.

I welcome your feedback. Please don’t hesitate to reach out through the contact section of the website if you would like to discuss, comment, or have any suggested edits.

[1] ISO 20022 For Dummies, SWIFT 5th Limited Edition

[2] Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication

[3] ISO 20022 For Dummies, SWIFT 5th Limited Edition

[4] A good but unnecessarily long review of multi-sided platforms is the book: Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms by Evans and Schmalensee