opening banking

Some 3,000 years ago the Ancient Greeks founded Western Civilization with their original ideas on philosophy, art, and science. This brilliance manifested through their architecture, reaching its zenith with the marvelous Parthenon. Many have appropriated this style’s symbolism since, but today it is fully claimed by one class - finance.

The emulation is as understandable as the symbolism is apt. Stability, logic, sanctity, and power are all characteristics bankers project to gain their customers’ most valuable asset - trust - quickly followed by their money. It works. Traditional consumers have been unable to help but feel the reverence these temple designs were initially designed to inspire.

The contrast between these traditional values and those of today’s “Digital Civilization” manufactured in Silicon Valley could not be more stark. After weathering countless geopolitical and cultural revolutions banking is faltering against a riptide of data, globalization, and radical consumer values. What is the value of banking privacy to a generation eager to share their account information with strangers on Reddit, let alone their photos on Instagram, sexual preferences on Tinder, and political views on Facebook? Is an ionic column relevant to consumers willing to digitally deposit their money with a ‘neo-bank’ called “Monzo”?

Establishment banks may have withstood this cultural sea change were it not for the rise of “Open Banking”. Briefly put, Open Banking allows authorized non-bank third-parties to easily access financial records and perform banking actions on behalf of bank customers. This concept fundamentally upends banking’s traditional business model and is poised to completely restructure the financial ecosystem. Here I will explore what Open Banking is today, and how it may reshape the financial industry of tomorrow.

open banking’s origin

Banking’s role has always been safeguarding information as much as currency. Strangers (and governments) knowing your wealth is expensive at best and dangerous at worst, which is why the concept of ‘banking secrecy’ has evolved into such a central tenet of financial services. (It is worth noting that when researching this article, I could not find a single example of a major breach of banking secrecy outside the modern era). Over time this relentless focus on privacy came to be an unquestioned aspect of all banking services and in fact has been codified into law within many countries, wherein sharing customer financial information without permission is criminalized.

This is all good and makes sense as financial privacy is healthy for any society. The trouble is that this principle became rigidly enforced by industry without question. The point of banking secrecy is to maintain customer privacy, not prevent sharing of their information outright. A customer may want their financial data to be manipulated outside the bank! While undesirable and cumbersome in past eras of paper bookkeeping, sophisticated digital data manipulation is now a growing demand within financial services. When differentiation lies in quantitative ability and creativity, a single bank may not be best-in-class in all areas.

This is an inconvenient truth for banks, who have never had to share ownership of the relationship between a customer and their money. To counter potential rivals, banks have made it difficult to export basic financial records from their systems. Despite best efforts to stymie customer demand, the market has found a way. Third-parties like Yodlee and Plaid filled this void by creating ‘screen-scraping’ tools for the everyday bank customer. These function by using customer banking credentials to automatically log in and copy records from the bank’s user interface. Collected data is then translated into a new format and applied to a variety of use cases, most typically for consumer spending analyses (like mint.com). Inelegant, vulnerable to hackers, and reviled by banks, the fact that these workarounds have been so successful reflect the industry’s ongoing hostility to expanding access to financial records.

Limited financial record access appeared the status-quo but for growing global awareness of digital records and questioning over their ultimate ownership.

financial data today

Who are you? Your facial features? Your place in the community? A government serial number? How about your credit score and payment behavior?

The question has gained renewed interest in the wake of widespread digital tracking. The digital footprints left behind in modern life reveal intimate behavior, whether its entertainment preferences on YouTube, medical concerns via Google searches, or private conversations overhead by Amazon’s Alexa. This information, along with its surrounding context or ‘metadata’, is now meticulously cataloged, stored, and used by a multitude of industries for a variety of purposes [1]. If our behaviors define us, it is a short logical jump to realize consumer identities are being captured and used for profit with little informed consent [2].

Digital tracking’s growing pervasiveness and general ‘creepiness’ (for lack of a better term) has forced broader discussion on the extent of identity and data ownership. Where does industry’s logging end and individual privacy begin? Public discourse and private secrets? Nowhere has this conversation advanced furthest than in the European Union, where the decision of such data ownership has been made in favor of the individual thanks to the recent convergence of two pioneering regulations.

The better-known regulatory advancement is the EU’s Global Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). In this directive private industry is bound to treat customer data according to seven key principles:

- Lawfulness, fairness, and transparency: Conduct clear and fair data collection.

- Purpose limitation: Collect data for a specific purpose.

- Data minimization: Only collect what is needed.

- Accuracy: Store accurate and relevant information.

- Storage limitation: Data can only be kept for a limited period.

- Integrity and confidentiality: Keep data secure.

- Accountability: Companies will be liable for upholding these standards.

For financial services the implications are less operational than perceptual. Banks were already adhering to these tenets. Rather, GDPR has forced banks to explicitly inform customers on their storage and handling of financial records, where previously it was more of an afterthought to the mass audience. With GDPR, financial records have been established unambiguously as representative of one’s financial - and thus broader - identity. More than ever before banks now have clear-cut responsibilities in how they treat such information.

The second legislative advancement on financial data is the European Union’s Payment Services Directive 2, or PSD2, enacted 2016 and implemented 2018. PSD2 elevates into law the concept that customers own their financial data, and banks are merely vessels for holding it. Even further, PSD2 provides customers greater agency in how their financial behaviors are retained, processed, and executed. Practically, this means banks must allow customer authorized third-parties to access and manipulate financial records on a customer’s behalf. (This concept to be further explored below). The driving philosophy behind this effort is to increase competition and consumer choice within financial services by (i) reducing customer switching costs and (ii) weakening newcomer barriers-to-entry. Together GDPR and PSD2 codify financial data rights and have set a powerful precedent for regulators worldwide.

The confluence of a digitized economy, GDPR, and PSD2 have culminated in what we now call ‘Open Banking’. Under this scheme an individual’s financial activity is no longer limited to their primary bank or banks, but can be spread across as many vendors as desired. It is now easy for startups to enter financial services. While global implementation will be slow thanks to uneven regulatory advancement, it is certain the innovation enabled by Open Banking will inexorably sweep over and transform financial services.

here comes open banking

So what is Open Banking from a practical perspective, and how does it actually work? Although the term is used freely, I cannot find a consistent definition - all I’ve seen are overly technical and focus on the ‘how’ rather than the ‘what’. Summing up the thousand words above, I’ll add my take with a formal definition:

Open Banking: A banking paradigm granting depositors’ absolute and instantaneous control of their finances and associated data, including discretion over how each are stored and manipulated by both providers and third parties.

This model is currently enabled through Application Program Interfaces, or APIs. Generally speaking, APIs enable organizations to interact with one another in a programmatic, digital manner. For instance, your phone’s weather app may source temperature data from the Weather Channel by referencing - or ‘calling’ a publically accessible API. APIs are versatile. A translation website may submit input text to Google’s Translate API and receive translated language back. In this way APIs enable Open Banking by allowing customers to direct third-parties to manipulate finances held at their primary financial institution.

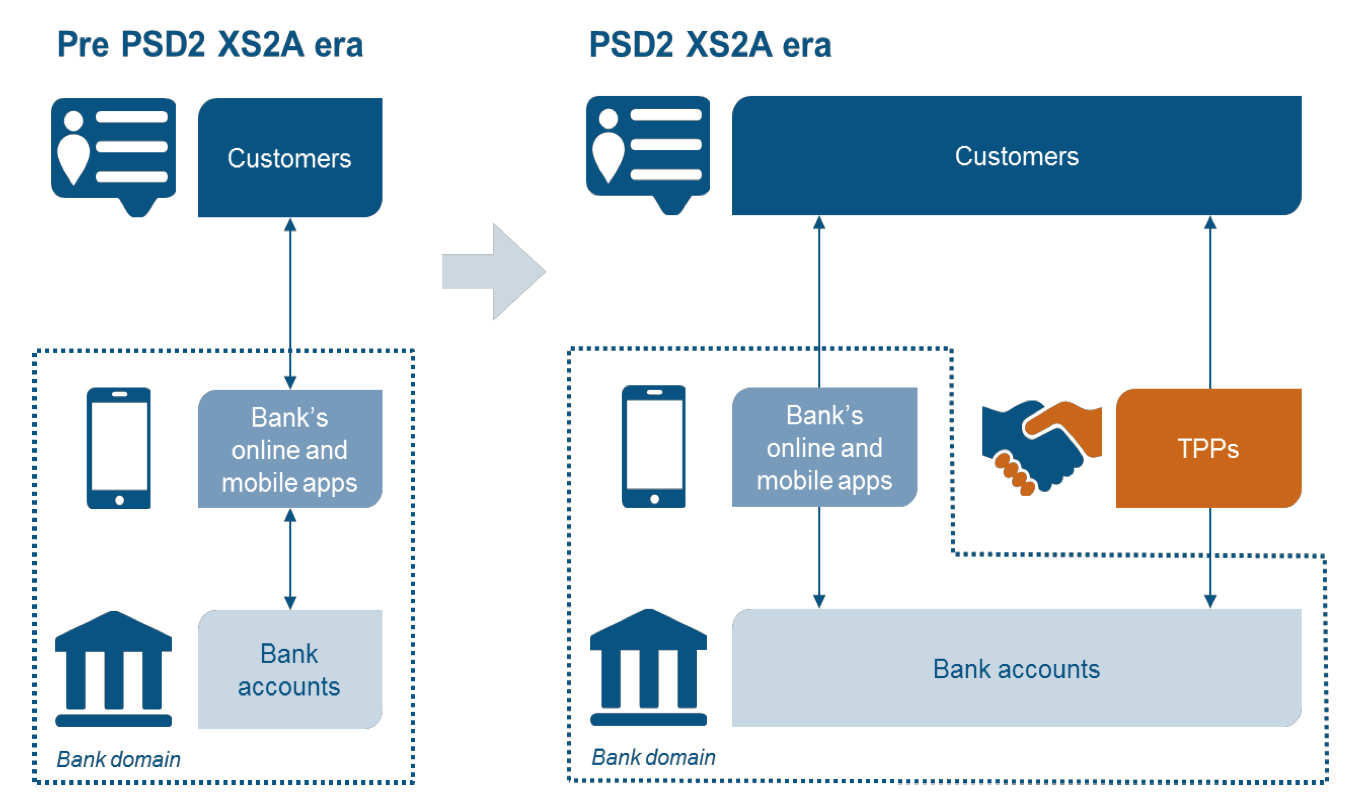

Figure 1: How Open Banking fits into the customer-bank relationship. Source, Nordea.

Figure 1: How Open Banking fits into the customer-bank relationship. Source, Nordea.

Open Banking can take a variety of forms as end-user consent is wielded by one provider to instigate orders across others. For example, a provider may use APIs to aggregate an individual’s financial records from a dozen different financial institutions to provide a holistic financial snapshot. In another instance, a vendor may optimize the distribution of funds across their customer’s accounts at various financial institutions to maximize interest while minimizing risk. A third provider may simply request user consent to display account balance information from one provider on a second provider’s website.

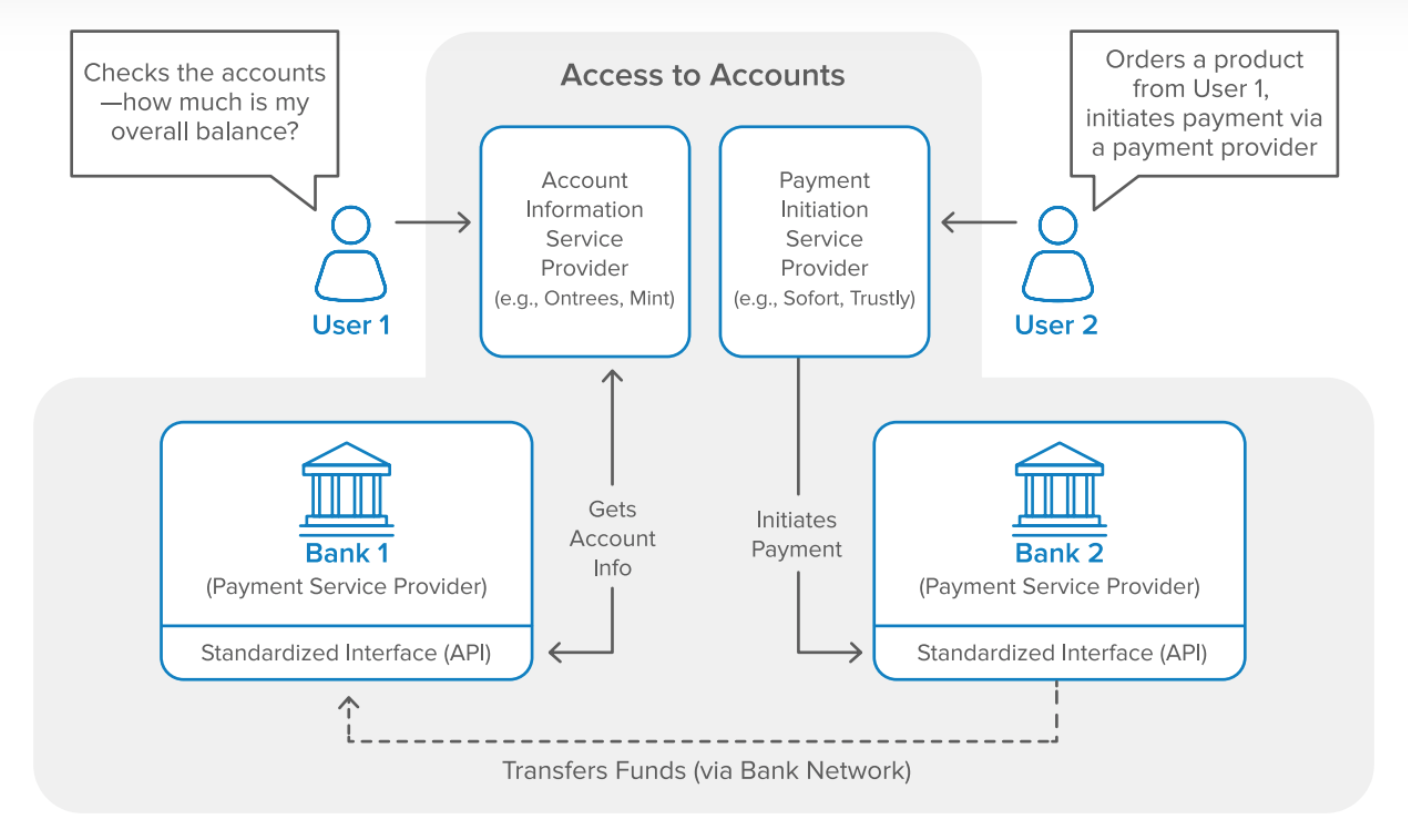

Figure 2: Simplified view on how Open Banking functions in practice. Source, Okta.

Figure 2: Simplified view on how Open Banking functions in practice. Source, Okta.

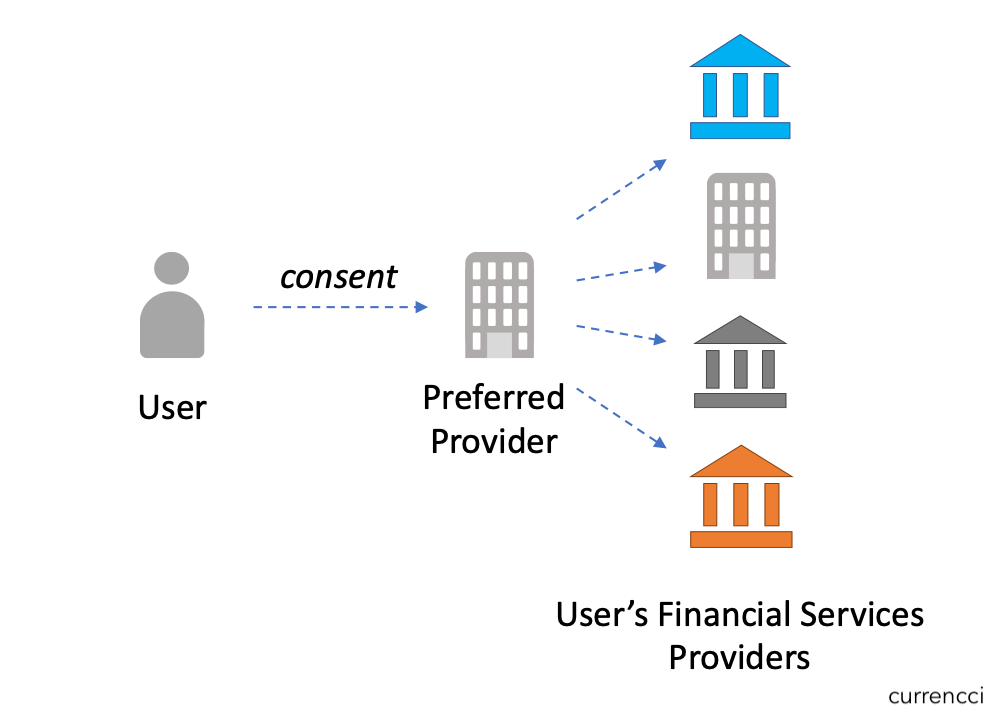

Thus, under Open Banking consent becomes finance’s dominant currency. With it, any given financial services provider has carte blanche to request data and submit orders on behalf of their customers at other vendors. This empowers those providers whose ideas (and branding) are convincing enough to effectively bootstrap their way to success off the infrastructure of incumbents. Similarly, providers unable to effectively compete are quickly left in the gutter.

Figure 3: Open Banking consent flow example.

Figure 3: Open Banking consent flow example.

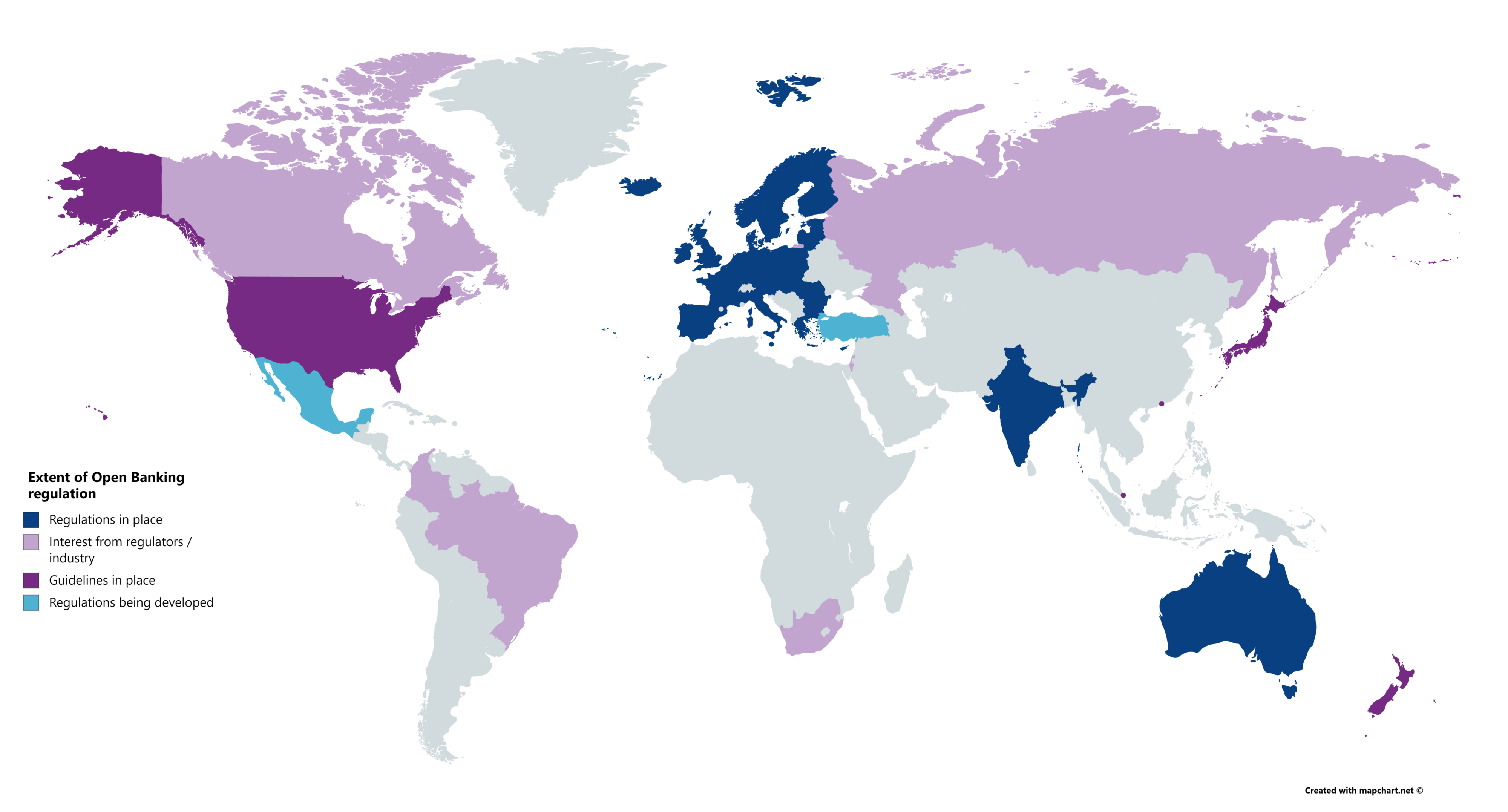

Of course, Open Banking’s consent-powered model can only exist in an accommodating environment. Up until the EU legislated GDPR and PSD2, Open Banking was an impossible concept. Now as it gains traction in Europe, governments and industry alike are moving quickly to confront the new reality it presents. Three regulatory approaches have emerged:

-

Regulator Led: Jurisdictions where Open Banking has been enforced by law. Governments in this category have determined financial services is mired in a steady-state of incumbency and legislation is the only path out. Consumer rights are paramount and granting end-users unfettered ownership over their data is a vehicle for introducing vigorous competition. These jurisdictions - notably the EU - are a strong influence forcing financial innovation worldwide.

-

Industry Led: Jurisdictions where regulators have proactively deferred to industry in implementing Open Banking (typically a combination of government caution and industry lobbying). Here incumbents are defining local limits and allowing only slow incremental change, though more risk-tolerant players will likely push the market towards greater innovation over time. Note regulators allowing an Industry Led approach typically reserve the right to impose Open Banking at a later point, to encourage industry progress towards a more open end state.

-

Wait and See: Jurisdictions where governments and industry are either too disorganized, cautious, or unwilling to respond to Open Banking and therefore ignore it. The result is a regulatory environment generally hostile to Open Banking as incumbents are reluctant to adopt its principles.

Regulatory approach dictates the pace of innovation, and the vulnerability of incumbents. Governments must take calculated risks - protect incumbents, or foster competition? Moving too quickly risks jeopardizing traditional banks, unregulated startups harming consumers, and upsetting the economy. Likewise, moving too slowly puts a country’s financial system at risk of being left behind as other countries innovate. Is sacrificing the influence of a country’s premier banks and disrupting the financial system worth the gains of fostering the financial world’s equivalent of Amazon? Clearly regulators are torn, though the drift towards fuller Open Banking seems inevitable thanks to the pressure from more progressive jurisdictions.

Figure 4: Map of Open Banking regulatory environments in the world today. Source, CitizenPay.

Figure 4: Map of Open Banking regulatory environments in the world today. Source, CitizenPay.

Forcing banks to offer APIs on manipulating the wealth they hold for customers truly upsets financial services. Long shielded by steep barriers-to-entry, incumbents must now innovate or die in face of a data-driven and internet-enabled competitive landscape. Over time, Open Banking will effectively trifurcate the financial services industry into (i) commoditized core providers; (ii) differentiated services; and, (iii) aggregators:

-

Commoditized Core Providers: Banks offering core banking services, such as savings and checking accounts, loans, and so forth. Given low customer switching costs in an Open Banking environment, these providers will compete for customers based on slim margins and branding. Unable to compete with digitally sophisticated new entrants, commoditized core providers will slowly cede the customer relationship and eventually primarily focus on a business-to-business-to-consumer (B2B2C) business model.

-

Differentiated Services: Providers dominating market niches with differentiated offerings. The competition Open Banking enables will continually attract new entrants with novel ideas, and those that succeed will go on to provide unique ‘best-in-class’ solutions. For instance, optimized urban apartment mortgages, pet insurances, or micro-donations. These players will introduce a greater amount of ongoing disruption and change to the broader financial services industry. These providers will pursue direct to consumer or B2B2C business models.

-

Aggregators: Providers of holistic financial services. In Open Banking, whoever wins the customer’s overall trust will serve as their primary conduit to all their wealth. Such ’Aggregator’ providers will provide customers all financial services within a unified environment, whether those offerings are from themselves or vendors (see above), through the API pipes Open Banking provides. A consistent and regulated environment will provide users safety, both from hacking as well as poor financial decisions. As gatekeepers, aggregators will wield massive influence over consumer privacy, service, and decisions. These firms may eventually serve as the loci of power within the financial services industry.

While the steady-state seems apparent, reaching it is anything but. Further, the broader implications of Open Banking are as profound as they are nebulous. How will consumers and businesses interact with their finances in an Open Banking future? Will greater control ultimately harm or hurt the customer? Will Open Banking foster ongoing innovation and competition, or does it simply replace one set of incumbents with another? While the details are impossible to predict, I believe we can confidently land the broad brushstrokes.

open world

Open Banking’s early results are…outwardly bland. EU incumbents awaiting Open Banking for the past several years are nervous out of the gate, and are cautiously foraying into the space with offerings similar to those of pre-Open Banking services, like simple money management. What’s more, banks have lagged in their implementation of functional APIs, crippling potential startups from accessing the data they need to function. This in turn deters would-be new entrants. Basically, bank incumbents are predictably reluctant to yield their grip on customer data.

Fortunately, these trends are slowly reversing. Over the past year bank APIs have grown more reliable and faster to query. Middle-men providers have sprouted up facilitating connection to APIs across multiple banks, and documentation has vastly improved. Such changes have accelerated Open Banking use - daily use in the UK has doubled year-over-year from ~10M to ~23M per day in January 2021. By no means is Open Banking fully implemented, but it has matured enough to allow for impactful and innovative services to start emerging.

The time could not be more apt. Open Banking is being met by the most transparent generation in history - Generation Z’s laissez faire attitude towards sharing personal information is now well-established. Whereas older generations may shy away from spreading their financial information across multiple providers, the Tik-Tok cohort is unabashedly willing to use digital providers. As much as financial transparency poses risk of abuse by security-sloppy providers, hackers, and surveillance states, it doesn’t appear Gen-Z will be deterred from trying out new services if it makes their immediate life easier. In what appears to be a mixture of progressivism, openness, ennui, and high-risk tolerance younger adopters will propel Open Banking to the dominant form of finance.

Open Banking’s initial success will be in money management services. As mentioned above these services already halfway exist through companies like Intuit’s Mint but are nowhere near ubiquitous because they are limited to read-only access to customers’ financial data. What’s the use of seeing a way to optimize your holdings, but having to manually manage it through multiple bank interfaces? Open Banking empowers money management providers by allowing consumers to not only see but also manipulate their finances at linked banks. In this way a money management provider can begin offering services to streamline and automate financial decisions on customer’s behalf, such as periodically rebalancing funds across various accounts. Possessing customer attention, data, and consent, these vendors will soon begin rapidly incorporating third party services and building their own original offerings. Thus, I expect these early successful money management pioneers will evolve into the centralized aggregators mentioned above. Just how other industries have been disrupted by tech giants (e.g. Google, Netflix, etc.) finance must soon reckon with the digital platform business model.

Emerging technologies will turbocharge innovation in financial sectors primed by Open Banking. Real Time Payments will allow for data-rich, low cost, and instantaneous transfers between bank accounts. Algorithms will ultimately bounce funds throughout financial services and providers looking for maximum yields and arbitrage opportunities, just like with high-frequency traders. Advances in digital identity and encryption will provide greater security and expand opportunities for third-party services to interact. As barriers between banks fall, banking relationships will be defined by superior user experiences, quantitative return, and other differentiators. Traditional banking services will be commoditized, and with them, banks who refuse to adapt.

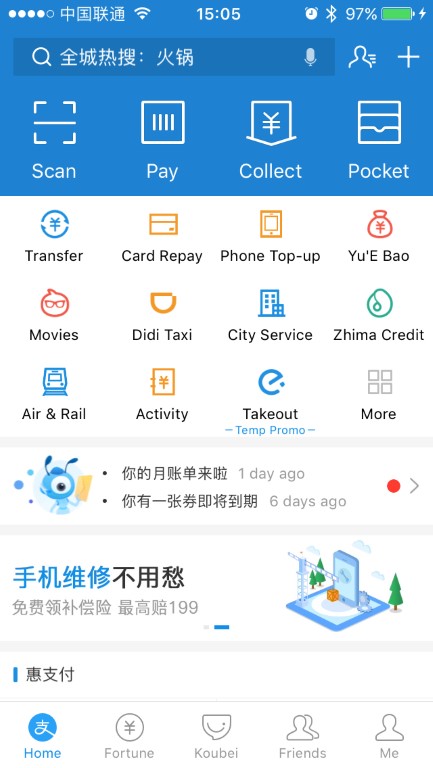

A hint of Open Banking’s future ironically lies in a country not known for its openness - China. There financial service aggregators have taken the country by storm - most notably through the dominant players Alipay and WeChat Pay. The Alipay service is a single ‘mega-app’ which provides users with a holistic view on their finances. In the app, a user can invest in an index fund, transfer funds to friends, view account balances, make in-store payments, shop online, receive paychecks, and more. It is astounding, it is convenient, and it just makes sense from a user’s perspective. Though the underlying infrastructure is completely different than that of Open Banking, the end-user experience is likely a strong predictor of financial services worldwide over the next few decades.

Figure 5: The Alipay app’s home screen . Source, PayPlusInc.

Figure 5: The Alipay app’s home screen . Source, PayPlusInc.

In China these two powerful aggregators are bringing legacy banks to their knees. Alipay is used by over 1.3 Billion people. Who do you think they associate with their finances, Alipay or their bank? While the data is not publicly available, it is obvious Alipay and WeChat Pay are aware of and wield massive influence over the decisions their customers take with their money, whether by user-interface design or unilateral control over available functionality. The Chinese government has recognized this power and is now embedded in these providers. Who knows how they will use this power.

Other societies must take note. The power Open Banking offers end-users can just as easily be flipped and used against them as aggregators scale. As noted elsewhere on Currencci, intentional behavioral science must be incorporated by design and customers clearly informed on why to make recommended financial decisions. Positive application of these principles could reduce wealth inequality, uplift those in poverty, and reduce the financial angst of billions. Regardless, it is entirely possible Open Banking may lead financial services from one set of incumbents to another! Ultimately, it is up to regulators to determine the outcome, though legislation like Open Banking which fosters competition for the sake of end-customers.

open doors

Today we live in a golden age of financial innovation. Open Banking has let in a fresh breeze of competition to an industry which has been relatively staid for literally hundreds of years. Transparency, rather than secrecy, is becoming finance’s new rallying cry as customers eagerly look to aggregate, then spread their financial lives across providers. For innovators looking to reinvent finance and make an impact, look towards Open Banking. Its time for our industry to re-earn the ancient Greek architecture we have long claimed as our own.

I welcome your feedback. Please don’t hesitate to reach out through the contact section of the website if you would like to discuss, comment, or have any suggested edits.

[1] It is worth noting that many U.S. companies collect information without knowing what they will use it for.

[2] Yes, Terms & Conditions exist, but are (i) too complex for laypeople, and, more importantly, (ii) digital services are increasingly unavoidable aspects of modern life. Consumers effectively have no choice but to agree to them.