ending money laundering

The UN estimates nearly 2% to 5% - or roughly two to five trillion dollars worth - of global GDP is illegally laundered. For reference, the GDP of France is ~$3T. How is this possible? Worldwide, preventative systems are intrinsically broken and enforcement lacking. This essay reviews how and why we’ve reached this state, and delves into what can be done going forwards to staunch this deluge.

money laundering 101

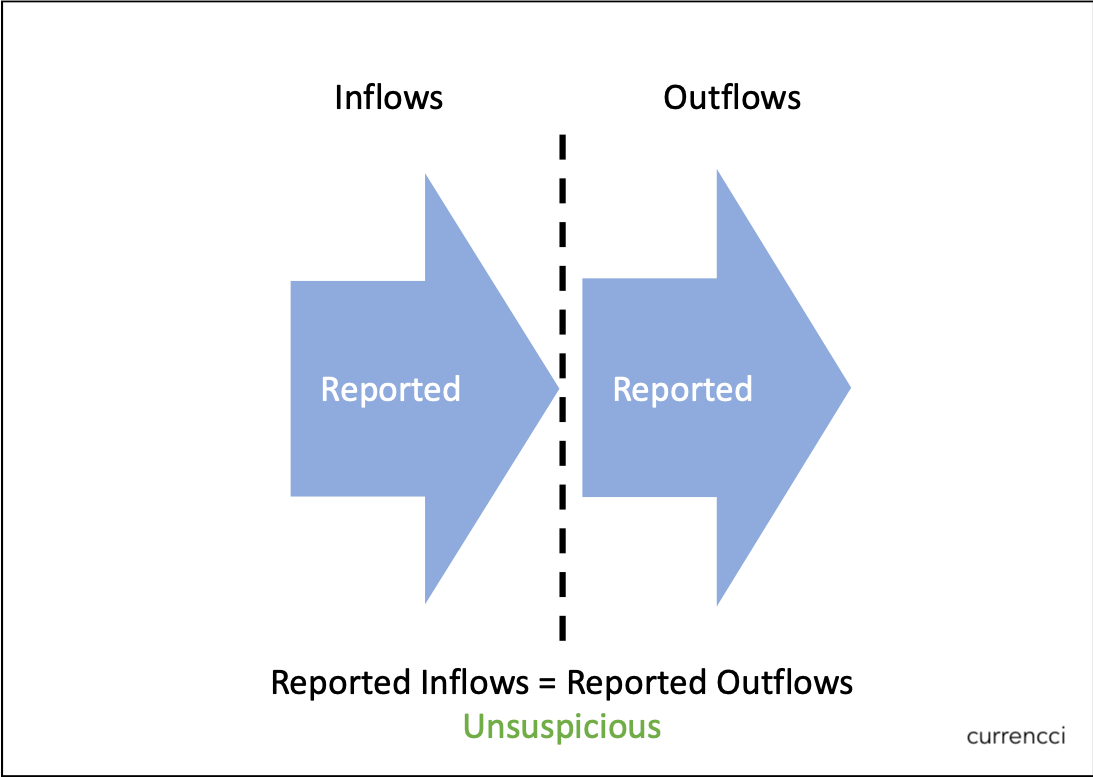

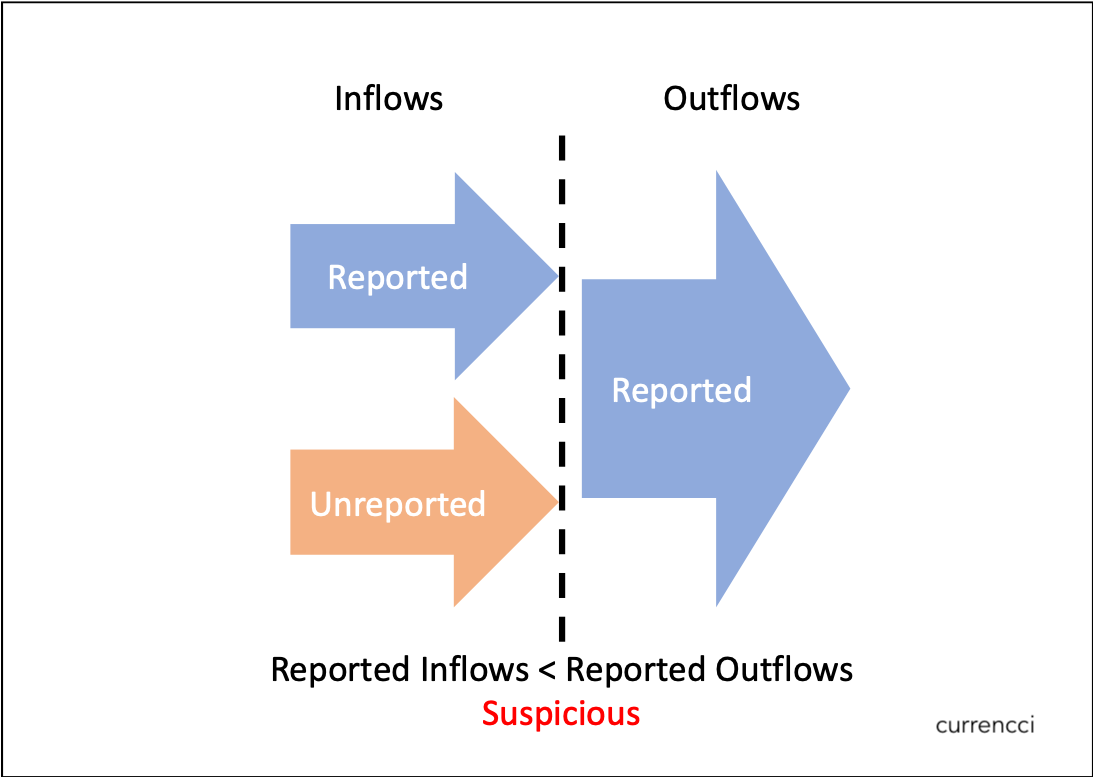

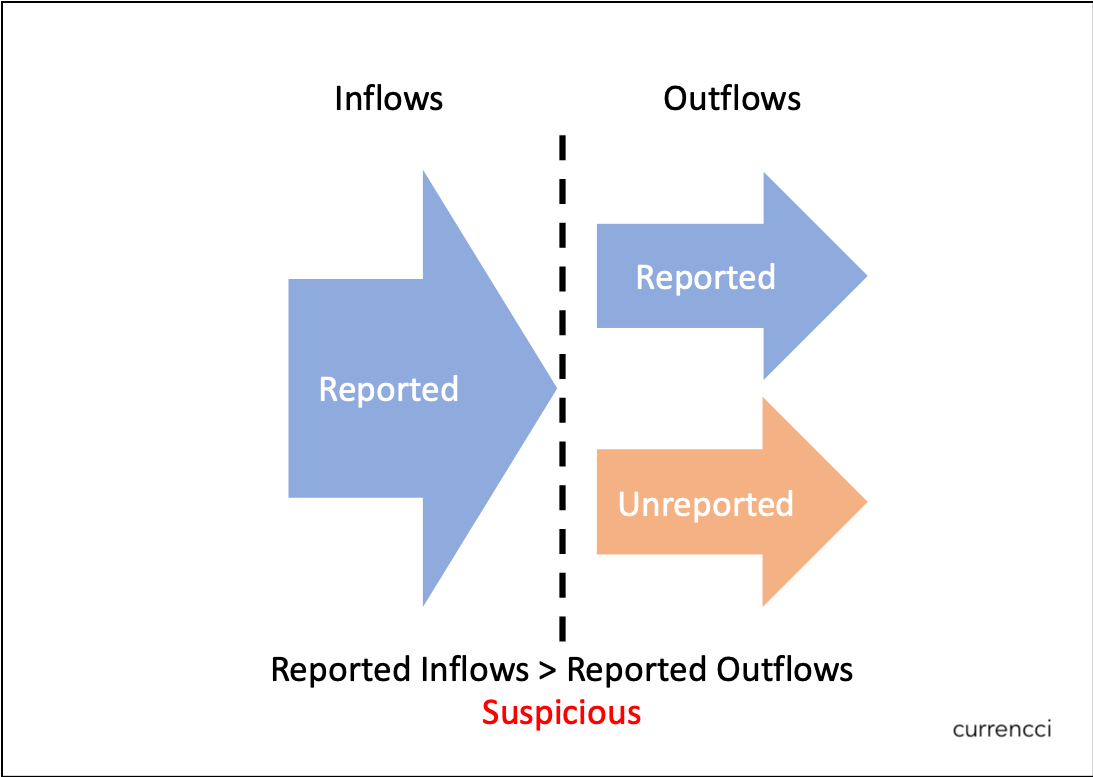

Your financial inflows and outflows reveal a lot about you - who pays you, who you pay, how much, when, and so on. Reconciling these flows not only helps you budget but also enables third parties to evaluate you, particularly governments when calculating taxes. Conversely, discrepancies in reconciliation raise suspicion of ‘hidden’ funds acquired or spent illegitimately.

Figure 1: Non-suspicious, normal payment flows reconciliation.

Figure 1: Non-suspicious, normal payment flows reconciliation.

Money Laundering is the process of legitimizing inflows and outflows of otherwise illegal money to lend the appearance of a balanced reconciliation. Without it illegal funds would be unusable in the financial system and rendered effectively useless. Thus money laundering is the foundation of nearly all economically-motivated crime (as opposed to psychological, political, or other criminal motivations) and preventing it a major priority for government and society.

Figures 2 & 3: Suspicious payment flows reconciliations.

Figures 2 & 3: Suspicious payment flows reconciliations.

Why go through all the trouble of money laundering? Imagine you received a bribe of a suitcase filled with $100 bills. How could you invest it in real-estate, a new car, or invest in retirement without raising attention? Without access to banks and the formal financial system, large amounts of money are useless! The answer for criminals is money laundering.

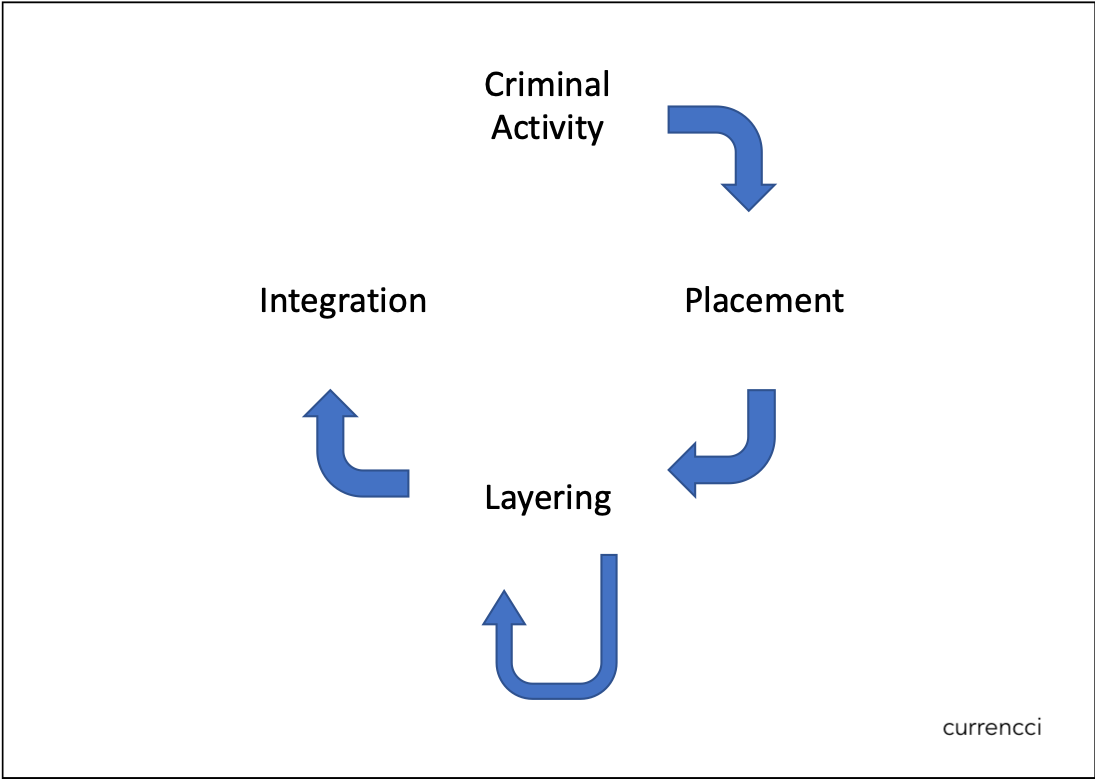

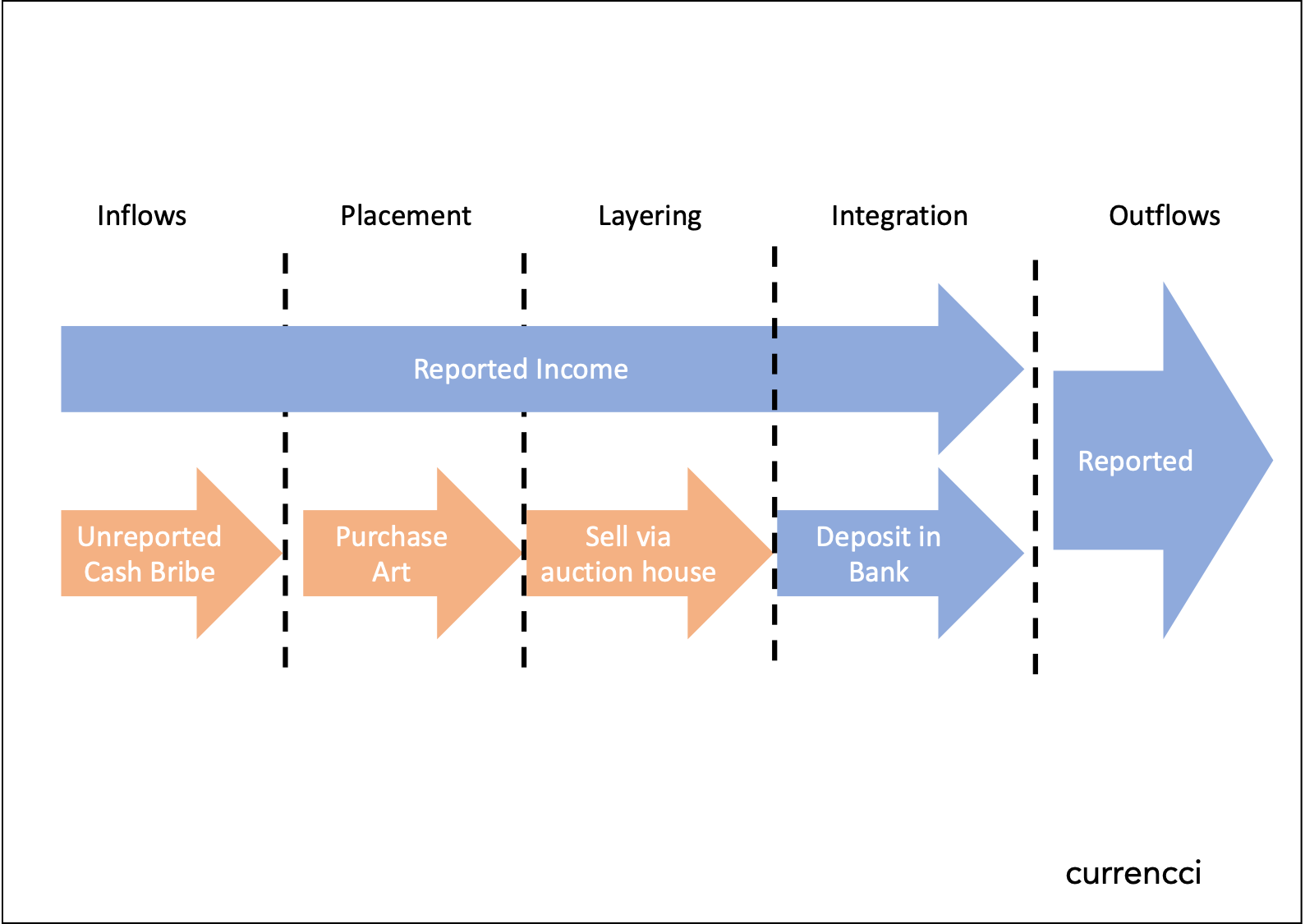

Money laundering consists of three sequential steps: placement, layering and integration.

- Placement is moving funds into the financial system.

- Layering is directing the funds through various forms to obfuscate their original entry point.

- Integration is spending the laundered funds with third parties to extract legitimate value.

Figure 4: The money laundering framework.

Figure 4: The money laundering framework.

Figure 5: A potential money laundering process from a reconciliation perspective.

Figure 5: A potential money laundering process from a reconciliation perspective.

This basic process is universal to all money laundering and used by a wide range of criminals. Small time drug dealers to corrupt businessmen to rouge nation states all rely on similar, known, and time-tasted tactics to legitimize their ill-gotten gains and sustain their operations. The resulting ‘dirty money’ encourages further criminal activity, poisons above-the-board business, and damages the trust underlying society and commerce. Unfortunately this is all despite massive efforts to prevent and eliminate money laundering.

preventative measures

The origin of Anti-Money Laundering (AML) is shockingly recent. Historically, law enforcement worldwide focused single-mindedly on the crimes committed to obtain illicit funds, rather than how they were spent. This view shifted with the charging of Al Capone, a notorious mob boss, in 1931 with tax evasion. The insight here was that identifying and charging a criminal with unreconcilable money flows is far easier than proving the crimes committed to obtain those funds. In other words, once a discrepancy is found, it is up to the accused to prove their origin. In 1970 this culminated with U.S. Congress introducing first-of-its-kind AML legislation making the act of money laundering a crime, along with a slate of novel preventative measures. Many other countries soon followed and AML legislation has evolved since.

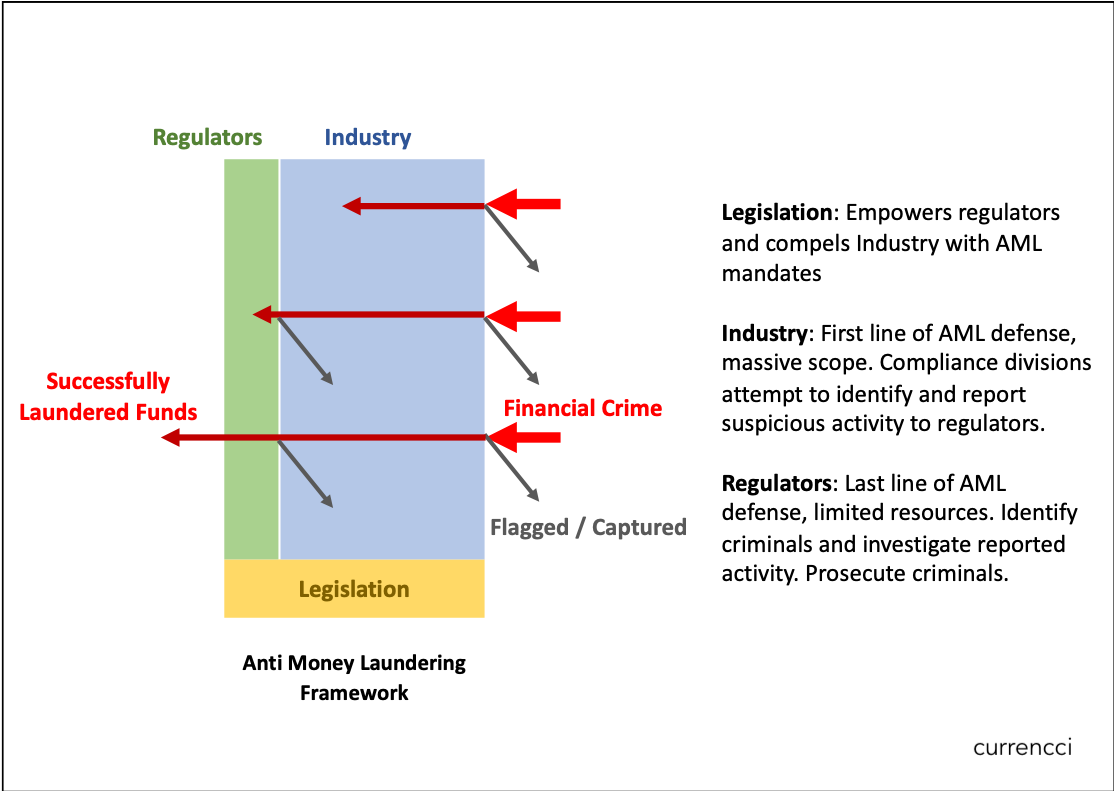

Today AML consists of a framework powered through a trifecta of legislation, regulators, and ‘deputized’ private entities. Together they provide a holistic screen guarding the broader financial ecosystem from illicit funds. While their influence varies between countries, their basic functions are consistent globally.

Figure 6: The AML framework.

Figure 6: The AML framework.

Legislation drives all AML. Legislative mandates empower enforcement and its punishments deter potential criminals. Notably, it funds and defines the roles of regulators and enslists industry’s participation in AML efforts. Drafted by legislators and informed by law enforcement, regulatory agencies, industry, and lobbyists, AML legislation typically moves slowly to avoid causing any unintended negative consequences. Major AML legislation includes the Banking Secrecy Act (BSA) of 1970, the US Patriot Act of 2001, and just recently the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AMLA).

Regulators serve as the financial system’s loci of power in AML. Their primary mission is serving as the ’deterrent’ to would-be money launderers through rapid detection and strict prosecution of law-breakers. Practically, this translates to guiding, facilitating, and empowering enforcement of AML statues. Intriguingly, regulatory jurisdiction encompasses all dealings of its currency globally - meaning dollars spent in Zimbabwe are just as subject to U.S. laws as those spent in Chicago. Needless to say this leads to considerable international friction. In the U.S., the chief AML regulator is the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FINCEN), a bureau of the US Treasury Department. FINCEN’s responsibilities include collecting financial data flows from public and private financial networks, coordinating domestic and international AML enforcement, and supporting policymakers. Law enforcement use regulator’s support to, well, enforce AML. Notable regulatory enforcers in the U.S. include the FBI and the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

The third and final participant group necessary to enforce AML is private industry. In the same way police rely on witnesses to report crimes in their absence, governments rely on financial services providers to prevent obviously illegal business and report suspicious customer activity. Given industry unwillingness to halt and / or report potentially profitable business, participation is now mandated through legislation. Today adherence to these laws within industry is now handled by ‘governance’ divisions staffed by ‘compliance officers’. Key activities include:

- Know Your Customer (KYC): Banks must ensure their customers are not known criminals, terrorists, or otherwise sanctioned by the government.

- Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs): All transactions above a set threshold must be flagged to the regulator

- Suspicious Activity Reports: (SARs): Behavior indicative of illegal activity must be reported to the regulator using a standard form.

The private sector’s responsibility in halting AML ends with its reporting. Once submitted to a regulator, financial service providers are effectively freed from liability if any illicit activity does indeed occur. Likewise, unreported behavior resulting in known criminal activity renders the provider exposed to fines and other serious penalties.

Complying with AML mandates quickly grows difficult with more customers, and is a massive undertaking for international banks handling millions of customers and billions of transactions. Today a massive industry has grown to support banks in meeting their AML compliances, from KYC software vendors to AML consultants to industry associations offering compliance training. Growing globalization paired with ever-sophisticated technologies has resulted in hundreds of thousands of reports being passed to regulators annually.

The interaction between legislation, regulators, and private entities in enforcing AML is akin to a spider’s web. The legislation provides the web’s design and placement, the private entities the webbing, and the regulators the spider itself. Ideally when all three parties operate together criminals are captured, however, in today’s system all too many fly away unharmed.

cracks in the foundation

This common framework used to combat money laundering is stronger in theory than practice. Each of its pillars are fundamentally vulnerable to various weaknesses which diminish the overall system’s effectiveness. When compounded together the net result is the trillions of dollars of illicit money flowing through and rotting the worldwide economy.

legislative woes

AML efforts are handicapped at the onset by ineffective legislation. To be fair, I don’t accuse the majority of legislators to willfully writing and passing weak AML laws. Rather, as mentioned earlier, lawmakers are reluctant to tinker with their economy’s inner workings in order to avoid causing any damage. These concerns are amplified by the extremely powerful financial services lobby, whose mandate is to minimize bureaucratic ‘red-tape’ and legal liability while maximizing potential profit. The industry’s negative influence on AML legislation is only exacerbated once new legislation is finally passed, as stricter requirements lead to a larger supporting industry which in turn leads to greater industry inertia and reluctance to change the status quo. A final negative pressure on legislators is that the rich are typically involved in politics and value financial privacy. Not exactly a constituency legislators enjoy displeasing.

Disparate regulation causes even more issues. In today’s globalized world, individuals and companies alike are able to move money across borders and exchange currency relatively easily. This is a nightmare from a legal standpoint. Where does applicability of one nation’s laws end and another’s begin? As far as the U.S. is concerned, essentially all dollars and value processed through the U.S. financial system is subject to U.S. law. As the U.S. dollar is the world’s most important currency - the most common medium for international trade, the foremost reserve currency, and the official currency for a host of other countries - a vast swath of international finance must adhere to U.S. law in addition to their host country. Though sympathetic legislators may seek to standardize rules, local requirements all-too-often take precedence.

Such legislative discrepancies provide fertile ground for money laundering. Weak local legislation allows financial service providers to tend towards the bare minimum of AML procedures. Though technically subject to its regulations, many non-U.S. financial institutions find themselves beyond the reach and attention of U.S. regulators. As such, their reporting is all too often de-prioritized, flawed, intentionally inaccurate, or even disregarded outright, leaving easily accessible conduits for the initial ‘placement’ step of the money laundering process.

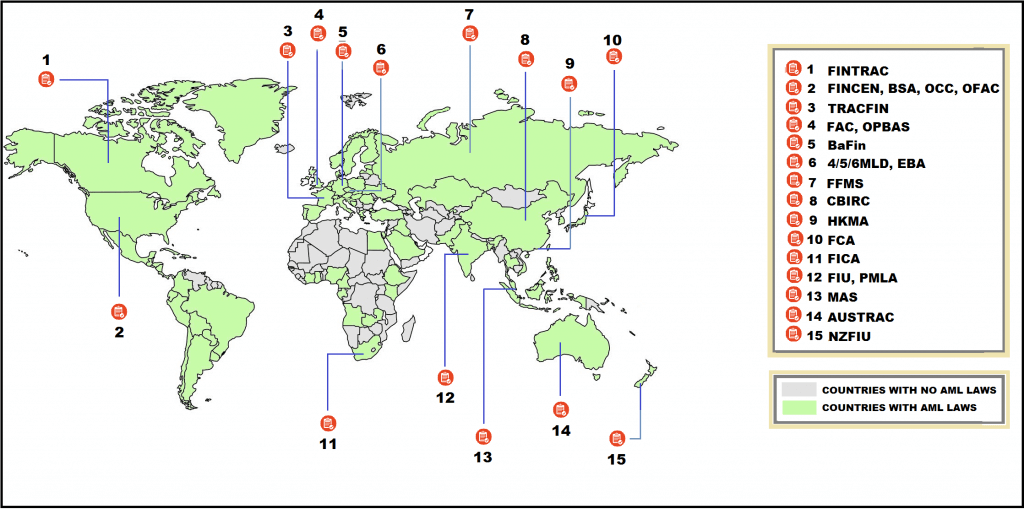

Figure 7: AML Regulators worldwide. Note the many countries lacking AML enforcement. Source.

Figure 7: AML Regulators worldwide. Note the many countries lacking AML enforcement. Source.

Remarkably, in some jurisdictions legislation is aimed at creating such discrepancies to advantage the domestic economy! Blithely termed ‘Tax Havens’ are jurisdictions imposing little to no taxes on foreign funds and permitting fund ownership secrecy in order to attract foreign investment. Though funds flowing to and from such countries are typically flagged for closer inspection, little can be done to understand the provenance or destination of such money. What’s worse, such jurisdictions legalize for the rich and powerful what would otherwise be straightforward tax evasion (e.g. corporate tax structuring by large tech companies in Ireland and Luxembourg). Other countries offer financial privacy for non-tax reasons with the same result - shelter for would-be money launders. Most notable are certain jurisdictions within the otherwise AML progressive United States, which in 2020 was ranked second worst country in helping individuals hide their finances from the rule of law.

Clearly, issues with disparate legislation are not limited to international boundaries. Varying legislation within countries can provide opportune discrepancies for criminals to launder ill-gotten gains. A prime example is Delaware in the United States, where up until recently companies did not have to disclose their full legal ownership. For a would-be money launder such a structure allows for easy obfuscation within each of the ‘placement’, ‘layering’, and ‘integration’ steps.

Weak rules paired with patchwork legislation offer plenty of opportunities for money launders to avoid restrictions and ‘clean’ their money. Through them many of the techniques criminals rely upon are passed over or even explicitly allowed. For most criminals however, ineffective legislation does not completely enable the money laundering they need. Unfortunately bad actors can rely on complementary deficiencies with regulators and in the private sector.

all bark and no bite

Regulators are tasked with ensuring AML legislation is enforced in an effective and comprehensive manner. Many of the brightest minds in finance are drawn towards the mission of keeping financial systems safe and fair. Alas, their efforts are frequently stymied by legal limitations, political interference, fragmented approaches, inadequate resources, and ineffective tools.

Inherent constraints on legal authority hamstring regulators everywhere. As mentioned previously, globalization allows funds to be moved relatively easily across jurisdictions - whether wire transfers or smuggled cash. A standard money laundering technique is to transfer money throughout as many intermediaries as possible in the ‘layering’ process, and this includes cross-border transactions. Transferring funds between countries is an excellent way to obfuscate the provenance of funds as international banking IT systems struggle to effectively transfer data with one another, translation errors drop meaning, and reporting requirements change. Investigators seeking to trace cross border transfers must enlist the cooperation of foreign peers. Regulators worldwide work diligently to form cross-border partnerships to achieve common AML goals, yet these unions are all to vulnerable to fickle geo-politics (e.g. Brexit).

Like any other government arm, AML regulators are subject to political or even internal interference corrupting their mission. Though the degree varies by quality of the government, even leading developed countries struggle with political appointees motivated by external goals. For instance, the former U.S. Attorney General William Barr’s daughter took a position at FINCEN while he was in power. Corrupt? Not necessarily, but it is difficult to imagine her applying an unbiased eye towards the multitude of convicted money launderers in the former Trump administration’s orbit. A more explicit example is found in Switzerland, the birthplace of bank secrecy and still a preferred tax haven for global elites and despots alike. It recently came to light the former attorney general and his cronies in the federal criminal-law system were willfully soft-peddling prosecution of foreign thugs in exchange for bribes. So long as regulatory agencies are exposed to corruption their effectiveness will be wanting.

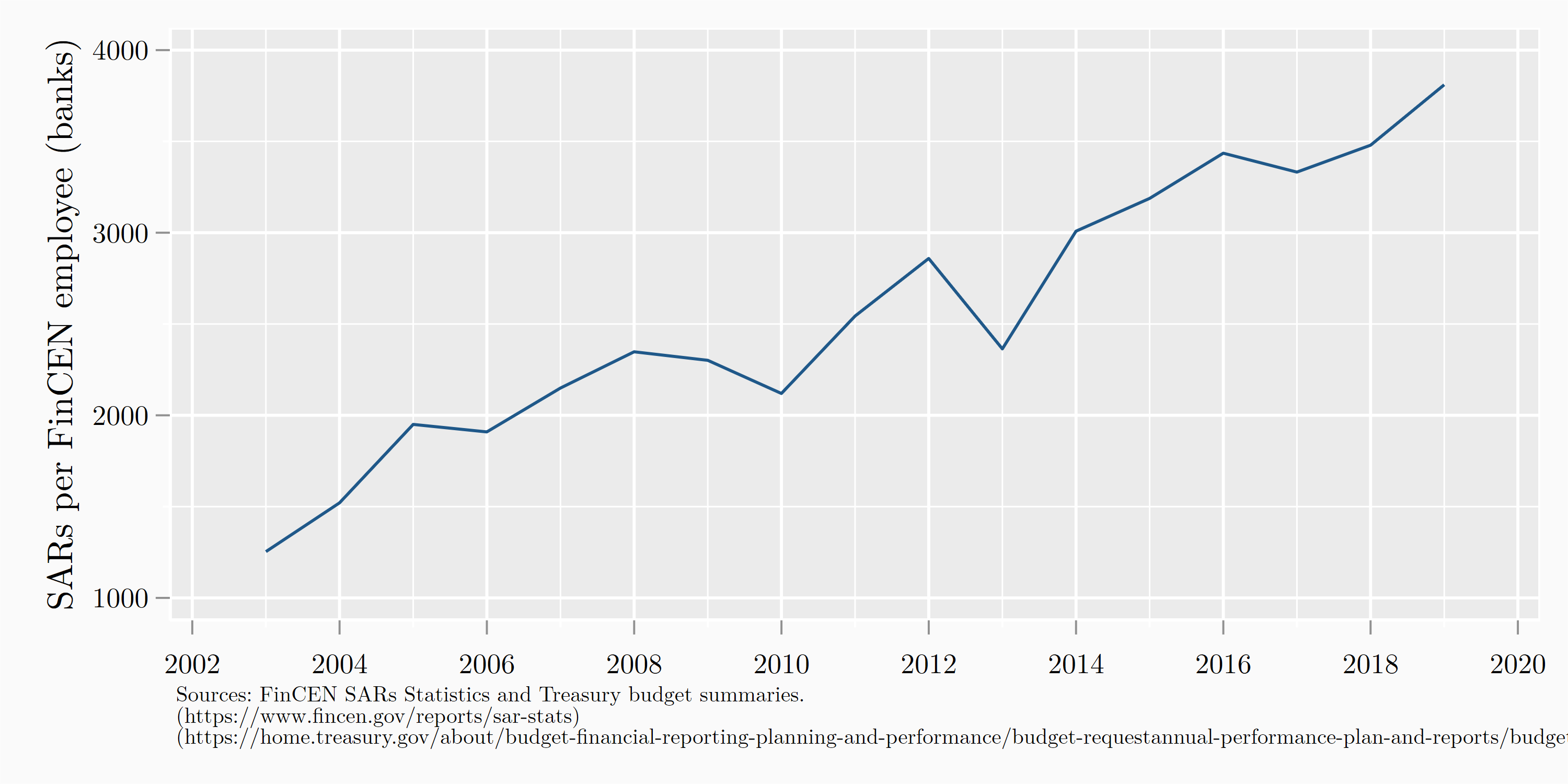

Regulators and AML-focused law enforcement also struggle with insufficient government support. Considering the dollar value of money laundering and the damage financially-motivated crime causes society, the funding allocated towards AML is shameful. FINCEN, the main U.S. AML regulator employees ~350 staff and was budgeted ~$120M in 2020 which is, as one economist forlornly pointed out, less than the budget of the latest Jumanji movie. Indeed, FINCEN receives over 2.2 million SARs per year - far more than they can process. It is a well-known secret amongst compliance officials that the vast majority of SARs and other financial crime reports go unread. Regulators are simply unable to make any significant progress in containing money laundering with such limited resources. Further, enforcement agencies with little centralized support are subsequently forced to prosecute fewer cases.

Figure 8: SAR reports per FINCEN employee over time. Clearly most reports are never investigated, and those that do lack the attention they may warrant. Source.

Figure 8: SAR reports per FINCEN employee over time. Clearly most reports are never investigated, and those that do lack the attention they may warrant. Source.

AML regulation is further hindered by fragmented ownership between competing governmental bodies. At the U.S. federal level alone at least 40 unique offices are responsible for combating money laundering, spread across nine different agencies. Though FINCEN presumably leads U.S. AML efforts its ability to strategically coordinate AML regulation across dozens of government bodies along with thousands of private sector financial services providers is doubtful.

The final and greatest regulator handicap is their inability to punish enablers of money laundering. Whereas punishments for money launders can be quite harsh (albeit most white collar criminals clearly get off the hook), penalties for those individuals and organizations which abet it are shockingly light. Paired with the difficulty in or unwillingness of prosecutors towards charging individuals in lieu of organizations - thereby limiting managerial accountability - banks and the individuals leading them have few reasons to aggressively invest in AML. Consider some of the major penalties regulators can issue banks caught facilitating money laundering either intentionally or through negligence:

- Commitment Letter: Non-binding agreement between defendant and regulator to improve AML capabilities

- Civil Money Penalties: Fines

- Deferred Prosecution Agreements (DPA): Binding agreement between defendant and regulator wherein if the defendant undertakes certain actions, criminal charges are dropped. (a.k.a. a get out of jail card)

- Charter Revocation: Revocation of the defendant organization’s banking license / charter.

‘Charter Revocation’ stands alone as the only truly business-ending threat regulators wield. Unfortunately, this would-be cudgel is rendered harmless by regulator’s inability to apply it! In today’s globalized world it is uncontroversial to assume most dirty money flows through a major financial institution for at least one stage of the money laundering process [1]. Given their economic and geo-political importance these banks are simply ‘too big to fail’ and impervious to criminal prosecution. Instead under current conditions convicted financial crime enablers are subject to mere slaps on the wrist. An outrageous fact that has been borne out repeatedly over the past decade Particularly egregious examples include:

- 2012 - HSBC: Found guilty of willfully laundering cartel money and avoiding sanctions on behalf of clients. Result? A fine of U.S. $875M and a Deferred Prosecution Agreement which after five years ultimately found bank AML protocols still lacking. There were no consequences to essentially failing the DPA. This was soon followed by two more DPAs accompanied by $200M in additional fines.

- 2014 - JP Morgan Chase: Found guilty of knowingly enabling the massive Bernie Madoff ponzi scheme and its associated money laundering. Fined U.S. ~$1.7B accompanied by a Deferred Prosecution Agreement. Recent investigative journalism accuses the bank of knowingly enabling billions more in money laundering.

- 2019 - Standard Chartered: Found guilty of allowing money laundering and sanctions violations. Issued Cease and Desist letter and fined over U.S. $1.1B.

- Ongoing - Danske Bank: Found guilty of facilitating over U.S. $200B in dirty money through an Estonian branch. Several executives charged, fines forthcoming.

- And the list goes on…

Regulators today cannot halt the global flow of illicit money. Money launderers enjoy scattered prevention and safety in numbers. Even worse, would-be enablers in the financial services industry clearly lack a compelling business case for investing in AML. Without adequate support from legislators and the private sector regulators will continue to lose this fight.

deputize this

Legislators may legislate and regulators may regulate but it is private industry who determines the extent of global money laundering. If all professionals and organizations in the financial services industry chose to really prioritize AML, financial crime would diminish to a trickle. The reason is scale. Finance ‘sees’ nearly all financial activity - governments don’t. The largest 15 banks in the U.S. manage over half of all bank deposits and a handful of centralized operators process nearly all electronic payments (e.g. cards, ACH, wires, etc.). Money laundering techniques are well-studied and technologies exist to automatically detect them. Why then, does private industry not do more to prevent it? The answer boils down to dollars and cents.

Effective compliance harms top-line revenue. Its premise is to proactively destroy near-term perceptible value by ‘sinking’ potential business deemed too risky. The trouble is that banks have clearly determined the risk of abetting financial crime is manageable! Consider the many recent examples of money laundering at some of the world’s most prestigious banks - and these are only those who’ve been caught. Today it is simply more profitable to violate AML rules than to fully comply with them. Without a strong business case for choosing compliance over non-compliance, financial service providers will never fully pursue AML.

This calculation is driven more by the cost of good compliance rather than the potential upside garnered from handling illicit money. Sure, the fees associated with serving 2-5% of global GDP is clearly attractive, but the overwhelming majority of finance professionals are not criminals nor do they aspire to be. Instead bank managers are hard pressed to invest limited budget in preventative measures with inherently un-measurable value. What is the cost savings of avoiding business with a single money launder? A thousand? For passing through $100 in dirty money, $100M, $100B? While the value is surely significant, so are the operational costs for a best-in-class compliance division. Lawyers are needed to adhere to and track compliance across numerous jurisdictions. An army of compliance officers are required to manually draft and submit mandatory reporting to regulators. Massive and sophisticated infrastructure is necessary to monitor and alert upon potentially suspicious activity across the entire business. These costs are no joke. Over a third of surveyed banks in a recent international study reported compliance costs more than 5% of their overall budget. In the same survey, 20% of respondents reported compliance costs were their biggest challenge in 2020 (the largest reported concern). To cut their losses, mainstream finance today has unanimously compromised on running mediocre to moderately effective AML. ‘Good-enough’ AML procedures prevent enough illicit activity to ensure an organization’s charter isn’t revoked if caught for abetting criminal behavior, all while minimizing costs.

As these massive costs stem from regulation the Private Sector lobbies hard to halt and repeal. Finance is a powerful lobby and legislators are unwise to ignore their needs. This causes considerable headwinds against any new AML legislation which could potentially increase compliance burdens.

AML technology is undergoing a particularly difficult renaissance. Nearly all major banks rely on decades-old core technology infrastructure which is woefully outmoded and increasingly incapable of meeting today’s financial crime. Though current technology offers exponentially greater function and performance, upgrade and integration costs are prohibitively expensive in all respects. Enhancements are therefore taking place slowly and in a patchwork manner.

Effective industry AML costs even spill over from industry to regulators. As submission of a suspicious activity report practically immunizes a provider from prosecution and over-reporting false alarms has no repercussions, financial services providers have come to file ‘defensively’. This practice shifts the onus of investigation from industry to already-overwhelmed regulators. This phenomena is concentrated among larger banks as accurate regulatory reporting is difficult at scale.

Compliance reporting is perverted amongst finance startups. Whereas large players find it expensive to take risks with compliance (in either direction), small players find it expensive to undertake more than the bare minimum, if at all! Startups obsessed with growth lack the luxury of dedicating limited resources to a function whose role is to slow the business down. An innocent de-prioritization at the onset can have disastrous long term consequences as workplace culture form, scale grows, and risk exposure increases.

The cost of strong compliance extends beyond business’ interests to those of their employees. Good compliance officers stop all risky deals, but a bank employee who stops all risky deals isn’t a good compliance officer. In other words, businesses run on revenue and careers are not made by halting it. This Catch-22 incentivizes compliance staff to perform poorly. This hopeless circumstance repels top talent and executive support, harming not only individual compliance efforts but also the general AML community.

Legislation, regulators, and the private sector each suffer in their own way in contributing towards effective AML and compounding the weakness of their complements. The final burden upon this system is that the environment in which they operate and the criminals they attempt to counter are constantly evolving.

Moving goalposts

Anti-Money Laundering’s challenges don’t end at home. Evolutions in the modern financial ecosystem continue to create opportunities for criminals to launder their illicit money. On the forefront of this change are crypto-currencies, the rapid surge of ‘fintech’ (financial technology) startups, and ever-increasing globalization.

Most obvious is the rise of non-government operated crypto-currencies like Bitcoin, Ether, Ripple and the like. Their dubious merits aside, these ‘currencies’ provide little to no internal mechanisms to halt or prevent money laundering. Instead their stark anonymity and minimal oversight has quickly attracted all types of criminal behavior in the few years since their mainstream adoption. Players within the industry are quick to disagree - with most quoting a popular industry report stating ‘only ~1.1%’ (~U.S. $10B) of all payments made using cryptocurrency in 2019 was laundered. The trouble is that this is likely a low estimate. In November 2020 the DOJ announced its seizure of $1B in bitcoin from the operators of the now-defunct ‘silk-road’ marketplace. That exchange earned this hoard through facilitating criminal activity and taking a percentage cut - criminal activity in the crypto-world surely stretches far beyond just one generally public(!) marketplace. Consider too, how researchers recently identified one individual or coordinated group recently manipulated the price of bitcoin up to unsustainable heights for easy profit.

Lawmakers, regulators, and industry have few tools to counter the money laundering risk posed by ‘crypto-currencies’. Lawmakers and regulators have limited jurisdiction over a system inherently without one, and industry participants can only influence those parties in the crypto-network willing to engage with them as customers. All three players are moving quickly to combat this emerging threat, but as long the potential for malevolent behavior is baked into these ‘currencies’ as a core feature they will remain the realm of crooks and the naïve.

In late 2014 financial technology suddenly became ‘Fintech’ and along with it, a tidal wave of investor excitement, corporate hyperbole, and outlandish conjecture. The traditional financial industry has always relied on information technology - whether morse code or mainframes - but has been late to adopt modern digital infrastructure. Countless new players have entered finance obsessed with the idea they could innovate where the incumbents couldn’t. Starting without legacy baggage, they envision ‘digital-first’ banks providing easy user-interfaces and AI-powered investing. A welcome vision in an overly staid and exclusive industry, except the ‘move fast and break things’ mentality is irreconcilable with ensuring a safe and regulatory compliant financial ecosystem. Compliance is difficult - and there are innumerable opportunities to make mistakes in basic AML procedures. Further confounding is that as Fintech’s stretch the concept of financial services through innovation, they fall outside the scope of existing AML regulation. Such gaps in regulatory coverage provide openings for creative criminals.

The final major evolution facing AML is the global economy’s growing interconnectedness. As peoples increasingly travel, live and work across borders international financial flows correspondingly grow. Growing legitimate financial activity offers a protective layer of ‘noise’ atop illegal international money laundering. Without superior techniques and resources, existing AML tactics could soon become overwhelmed by a flood of false alerts.

limited self-correction

“There is not a crime, there is not a dodge, there is not a trick, there is not a swindle, there is not a vice which does not live by secrecy.” ― Joseph Pulitzer

Financial crime is not inevitable. The vision of a global financial ecosystem without money laundering is immutable regardless of how broken current systems are. The challenge is in reaching this state. AML practically didn’t exist 50 years ago, and now entire government offices and industries are dedicated to its advancement. The secrecy, loopholes, and cracks in the global economy in which financial crime thrives are slowly being uncovered and rectified.

One of most significant recent advancements is the passage in the U.S. of the ‘Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020’ or the AMLA. It is a magnificent progression for AML legislation. Among its many provisions, highlights include:

- The Corporate Transparency Act: Ultimate beneficial owners of companies must be listed, thereby preventing criminals from hiding behind shell corporations.

- Foreign Bank Records: U.S. regulators now can subpoena the records of any account at any bank that maintains a correspondent relationship in the US - essentially all major banks everywhere.

- General Modernization: Various initiatives to modernize AML technology throughout the government and private sector

- Data Sharing: Advancing data sharing between financial institutions, and allowing for creation of industry ‘black’ and ‘grey’ lists of known criminal and suspicious customers, respectively.

- Greater Regulator Funding: Self explanatory.

- Expanded Scope: Encompasses emerging innovations in finance, including crypto-currencies.

- Whistleblower Enhancements: My favorite. Whistleblowers were formerly incentivized by a $150k reward for reporting financial crime under the BSA. Maybe appropriate in the 1970’s, but not much of an incentive for a banker risking their career. Now, whistleblowers are eligible for up to 30% of the collected penalty. In an era of fines regularly in the hundreds of millions and even billions, this will likely lead to far more whistleblower disclosures.

The AMLA addresses many of the most pressing issues facing AML today, and promises to significantly curtail existing AML flows. Even more, the act will undoubtedly pressure other governments to adopt stricter measures of their own. Bravo!

This milestone in AML legislation rides a steadily accelerating progression in AML technology within the private sector. The market has recently latched on to the opportunity in reducing the massive costs imposed by AML and associated compliance. Sitting at the intersection of ‘regtech’ (regulatory technology) and fintech, these innovators seek to supplement and even replace human review and decision-making in banking compliance. Most notable are efforts to apply the power of machine learning to faster and more accurately detect suspicious activity, as well as complete and submit SARs and other reporting automatically. Results are impressive - computers are far more diligent than their human counterparts, and won’t grow bored reviewing thousands of sequential false positives. Unfortunately, this progress so far has been limited to the private sector, meaning manual effort is still needed to receive, interpret, and pursue the leads generated by this superior reporting.

Finally, new payment technologies are bringing greater transparency to the overall financial system. In particular, as mentioned in an earlier article, Real Time Payments promise far richer payment information than is available today. Such data will enable regulators and private industry to better detect suspicious activity and ignore ‘false positives’.

Though welcome, such progress is far from enough as transparency without enforcement is meaningless.

Ending money laundering is not just possible but increasingly practical with today’s technology. The challenge now is finding the political will to enact the necessary changes. Namely, only a few key governments worldwide must move aggressively to enact a series of reforms to money management, tracking, and transmittal. If done correctly these could cascade into global change. Reform is needed not only across the main AML pillars, but to the basic framework itself.

At the most fundamental level global standardization is necessary around basic financial data and compliance requirements. Financial crime gravitates to the weakest entry / exit points in a system, so creating and enforcing strong minimum standards would prevent most illicit money from entering the financial system in the first place. Today, countries have a wide array of standards, and attempt to impose their own on their trading partners with limited success. This fragmented approach cannot succeed. All financial service providers within a given ecosystem must be held to consistent AML requirements in order to participate, especially with minimum standards around sharing customer KYC and contextual payment information. Further, such information should be easily and securely transmitted between member financial institutions. Such a rigorous standard could be enacted through a variety of mechanisms - trading blocks, banking associations, and so on. Already there are notable attempts to do so - particularly the Financial Action Task Force and the European Union’s AML Directives. However, they all have limited enforcement or reach or both. An effective system must dictate and hold members to its rules by binding law. Such a framework for information sharing would and should not necessarily impede on government sovereignty or citizen privacy. Compliance standardization will prevent universally agreed upon illicit activity.

A global cooperative approach is also needed to punish the bad actors proactively enabling financial crime. Some jurisdictions will always effectively legalize money laundering as long as there is an incentive to do so - notable examples include the Channel Islands, Cyprus, and so on. Those playing by the rules must be willing to enforce them by blacklisting and / or severely penalizing financial interactions with these jurisdictions. Creative legislation could specifically target the foreign money flowing through such tax havens while sparing otherwise innocent local inhabitants.

Modern AML legislation’s most remarkable trait is that in today’s globalized economy just a few - or even one - key jurisdiction(s) adopting a tougher stance could cascade into a permanent global legislative shift. As multinational companies expand they are finding it cheaper to standardize their operations according to the most profitable and / or strictest regulatory regimes in which they operate. A notable recent example is the GDPR digital data privacy directive in the EU. Though non-EU countries set less stringent measures on digital data privacy, no large firm is willing to abandon their EU business to avoid complying with GDPR’s data handling measures. To avoid onerous cross-market version controls as well as possibly risking non-compliance, many companies now offer GDPR-levels of data privacy across all markets in which they operate. In the same way, financial service providers are increasingly standardizing their international compliance operations to avoid running foul of the stricter AML regulations in their more profitable markets. All that is needed is for a legislative body in a key market willing to pass stricter AML policy.

White collar crime must also garner more aggressive prosecution. The solution is political - under numerous administration ineptitude and outright malevolence by politicians and political appointees in the justice department allowed numerous known money launders to escape unpunished. While worthwhile in other parts of government, justice departments clearly need fewer politically-incentivized decision makers. Furthermore, these offices should be better funded to offer competitive salaries to attract and retain career top-class talent.

Ending money laundering also requires better-equipped regulators. This stems from funding - more dollars means more training, manpower, and technology. The answer could be tweaking an old method - civil forfeiture. Remember, money laundering comprises 2-5% of global GDP. Why not tap into these flows and create a strong deterrent by using at least a portion of them to fund regulators? Governments should overhaul and simply civil forfeiture laws concerning laundered money found within the banking system. Further, a significant portion of these funds should be earmarked solely towards further AML enforcement. Potential government abuse could be avoided with ample transparency and harsh recourse for erroneous seizure.

For all the importance of strengthening AML legislation and regulators, the true shift must be in the financial services industry. Financial services are the ones who currently make the decision - intentionally or not - that tolerating and / or abetting money laundering is cheaper than AML compliance. This calculation must be flipped to end money laundering. Harsher punishments for facilitating money laundering are a good start, but not enough. Record breaking fines continue to be doled out to multinational violators, but bad behavior continues. Regulators must be willing to revoke banking charters and throw those responsible in prison. Why should a small time drug offender receive prison time when a banking executive has their violation written off, or pardoned? Private industry must move with purpose to avoid association with criminals.

Aside from stronger deterrents, private industry can be better motivated to pursue detection and capture of money launderers. Appropriately enough the answer could lie in economic incentive. Private industry should receive a significant financial upside in detecting and reporting financial crime. The AMLA and other whistleblower laws are on the right track - providing major financial awards to individuals who attempt to alert regulators. Future regulation must take this farther, by incentivizing organizations to pursue financial crime, akin to bounty hunters. Capitalism is based on efficient markets - let’s incentivize the market against, rather than for money launderers.

The compliance industry is well positioned for this change. Already compliance divisions, private investigators, due diligence firms, consultants, auditors and more are trained to find money laundering. Now is the time to empower them to aggressively pursue criminals for the sake of sure revenue, rather than the avoidance of intangible loss. Criminals will not stand a chance.

As for Fintech, crypto-currencies, and the like - it is clear financial ecosystems must be well-regulated to guard against criminal activity. Any new entrants to the financial services industry must be aggressively well regulated from the get go to avoid disastrous downstream effects. So long as innovation builds incrementally off of existing processes, it will not be stopped. Those building standalone systems should be encouraged, yet held to strict requirements to avoid unforeseen consequences.

Of course, all of this requires considerable public and government buy-in to work. The alternative is grass-roots motivation in industry to halt money laundering, or rather self-compliance. Impossible? Perhaps not. In fact, likely more possible than disparate governments coming together over a traditionally sensitive issue. I am confident such a framework exists - and raise a challenge to any would-be innovators to invent it.

clean money

A world without money laundering is one without financially motivated crime. This is achievable. The incentives just need to be recalibrated. Until then, existing frameworks will fail in staunching an unceasing flow of criminal funds, coursing throughout the global economy.

I welcome your feedback. Please don’t hesitate to reach out through the contact section of the website if you would like to discuss, comment, or have any suggested edits.

[1] Of course some bank charters have been revoked, but only for smaller banks less economically important and / or politically connected (e.g. First Bank of Delaware).