phase change | the rise of real time payments: part I

Today the payment industry is reaching one of the greatest inflection points in its history. Until recently, change in payments was a function of technological ability - a payment could only move so quickly, or contain such-and-such data. Soon payments innovation’s only limitation will be lack of imagination.

How so? This turning point is due to the culmination of a decades-long push to launch an industry-shaking technology called ‘Real Time Payments’, or RTP. In short, RTP offers the simplest, cheapest, and technologically advanced payment channel ever created. Little acknowledged outside of the payments world, RTP is positioned to upend entire industries, create new ones, and usher in a completely new age of finance.

I cannot overemphasize the importance of RTP and therefore publish this three-part series to offer readers a nuanced understanding of this revolutionary technology. Part I starts the series by establishing a strong contextual understanding of the main payment channels available today and their respective market roles. In Part II I dive into RTP and its functionality, and finally in Part III I will explore how RTP may directly and indirectly affect the payments industry, finance and society.

A brief note for clarity’s sake - in this series I review payment channels - mechanisms to transfer value between two points. There are numerous terms for these: “payment channels,” payment rails,” “payment networks,” “payment pathways,” and so on. I will primarily stick with the “channel” and “network” terms throughout this series in order to avoid confusion.

There are innumerable payment channels available in the world today, but only a few which really matter. In my review of payments channels I will stick to the five most prominently used: (i) Cash, (ii) Wire Transfer Networks, (iii) Global Card Networks, (iv) Automated Clearing Houses, and (v) Alternative Payments Networks. Each deserves its own essay, but for now we shall stick to key features, functionality, benefits and limitations of each. Readers familiar with these systems may skip this section, though are encouraged to refresh and refine their knowledge (particularly the immediately following section “what matters”).

Let us begin.

what matters

What makes a payment channel beyond just transferring value between two parties? As we’ll soon cover, there are a huge variety of interpretations of this basic operation, all providing various advantages and disadvantages. To focus this essay I have distilled the following variables characteristic to every payment system:

- Speed: General payment duration from initiation to completion.

- Governance / Risk: Transaction safety, or certainty. If channel governance is effective, trusted, and speedy.

- Data: Information conveyed. Whether the payment contains valuable contextual remittance information, or whether separate, additional information is required (e.g. an invoice).

- Direction: Whether payments are initiated by the originator ‘pushing’ funds to the recipient, the recipient ‘pulling’ them from the originator, or both.

- Irrevocability: If payments are final when made, or does one party or both have the ability to reverse the payment after completion.

- Cost: Cost per transaction.

- Ubiquity: Between whom and where does the network facilitate payments.

- Compatibility: Ease of transferring value into and out of the channel.

- Adaptability: How readily the channel adapts to changing technology and participant needs.

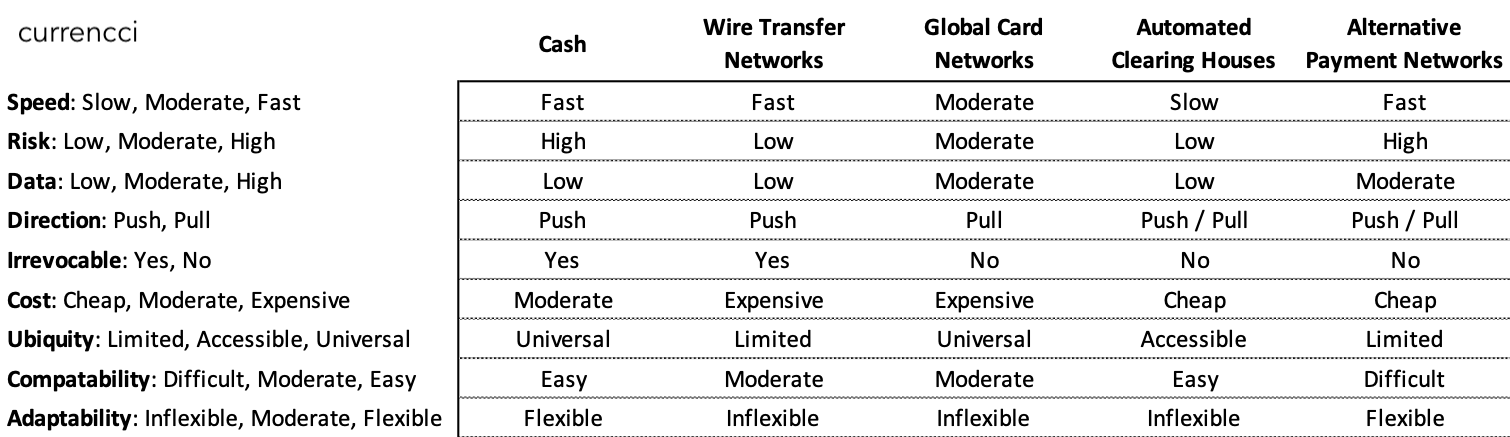

Our review leaves us with an understanding of how each stands both alone and relative to others. We will fill in nuances throughout this essay and revisit at this section’s conclusion, but let us start with a broad perspective.

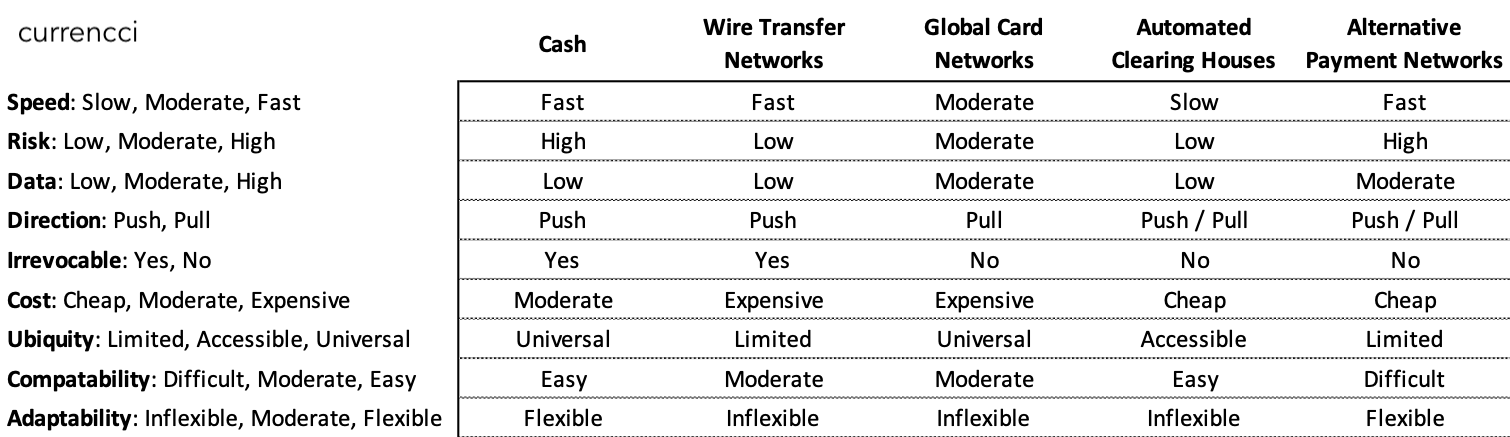

Table 1: Major payment channels overview, showcasing relative characteristics

There is no need to dwell on the above table other than to get a broad sense of network variability and how no channel is clearly superior to its peers.

A final note is that payment networks are ‘multi-sided platforms’ [1]. This is a powerful business model and a conceptual understanding is necessary to fully grasp why the payment networks operate as they do. The ‘platform’ aspect of the business is the underlying service provided by the operator, while the ‘multi-sided’ element is that multiple participants types are necessary for the business to function and create value. A familiar example is a mall. A mall operator will invite stores to rent spaces and shoppers to visit. Both participant populations are necessary for the mall to function, and higher participation by each only increases the utility - a mall with more stores provides shoppers more options, whereas more shoppers is good for stores’ business. In the same way, major payment channels require strong participation of both payment makers (Originators) and payment receivers (Recipients) in order to successfully function.

cash

Cash is a truly universal - even instinctive - concept. Though cash use is slowly declining in favor of electronic methods, it remains a dominant payment channel especially among consumers.

Where else to start but with Cash? The original payment channel hasn’t changed much since its conception - the originator physically passes specie to the recipient.

Figure 1: Cash payment. Value flows (in the form of physical currency) between the originator and recipient.

Figure 1: Cash payment. Value flows (in the form of physical currency) between the originator and recipient.

Is that it? Not quite - the nuance to cash in the details.

More than anything, cash is risky. Cash holders face risk of theft, counterfeit, and general loss. Originators lose all funds immediately upon payment, while recipients have no recourse until the payment is transferred. Governance falls upon local courts rather than any dedicated body, lengthening resolution times, costs, and certainty. Compounding these factors is cash’s anonymity and general un-tracability which make it the preferred choice for bad actors. Avoiding these fundamental risks has and continues to remain the main driver behind the development of all other payment channels.

Cash is also more expensive. It needs to be securely stored and transferred. Cash itself does not contain any contextual information, requiring separate records for bookkeeping. As cash isn’t auditable, records must be maintained and kept accurate. Even when kept these records are oftentimes non-standardized, making reconciliation and general bookkeeping difficult. Further, cash can be relatively easily lost or stolen. Taken together, these shortcomings add up - even in the advanced and relatively corruption-free European Union, it is estimated cash costs roughly 1% of the total GDP [2]. Though these implicit costs more than make up for its ‘free’ nature, it must be noted that humans are notoriously terrible at recognizing built in costs. End result? Cash is rationally more expensive, but emotionally considered the cheapest (i.e. free) method of payment.

Despite all this, cash is unmatched in sheer simplicity. Unless conducted remotely (via a courier) cash payments are free of intermediaries and related perceived costs. Cash is instant. Transfers don’t have to ‘clear’ or depend upon external factors. Cash is everywhere, almost everyone accepts cash (this is even mandated through legislation in some jurisdictions!). Cash is certain. Its irrevocability gives it a comfortable finality to all its transactions. Cash is easy. No infrastructure, specialized professionals, or extraneous prerequisites are necessary to complete a cash transaction. Finally, cash is comfortable. Nearly everyone on the planet intuitively understands how to use cash.

Cash remains the bedrock of the global economy; its faults have motivated creation of all other payment channels, while its simplicity offers a gold standard all systems strive towards.

wire transfer networks

Have you ever made an international transfer? How about a high-value purchase like a car or house down payment? This was likely a Wire Transfer, payments requiring high security and certainty. A venerable payment method, Wire Transfers are quickly growing more obsolete.

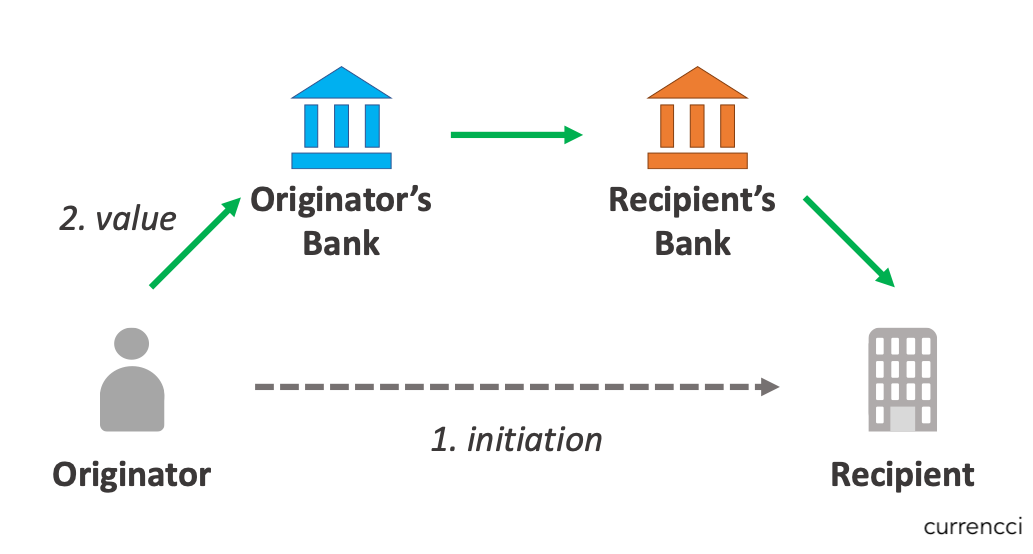

Figure 2: Basic flow of a wire transfer. The originator initiates the payment with the recipient, then directs their bank to transfer value to the recipient’s bank. In practice the connection between originator and recipient banks may involve intermediary banks.

Figure 2: Basic flow of a wire transfer. The originator initiates the payment with the recipient, then directs their bank to transfer value to the recipient’s bank. In practice the connection between originator and recipient banks may involve intermediary banks.

Wire Transfer Networks offer the best of yesterday - fast and safe, yet expensive and inefficient due to legacy procedures and technology. From the customer’s perspective they are relatively simple - a fee for a guaranteed safe and fast payment. Behind the scenes however is a confusing mess. Wire Transfer Networks generally operate through a hybrid of secure inter-bank messaging systems directing payments (i.e. wires), and intra-bank transfers completing them (i.e. transfers). Two wire messaging systems dominate: the SWIFT network for international bank-to-bank messages, and domestic networks run by federal governments for local messages. Wire Transfer Networks in aggregate are responsible for a large portion of value transferred globally, yet constitute a minority of the number of overall payments.

One of the most interesting features of wires is the funds themselves aren’t moved as part of the wire. Instead, the wire directs transfer of funds at the recipient from one account to another. In most cases funds themselves are never transferred as a discrete unit - rather their ownership is shifted. This process varies for domestic versus international wires.

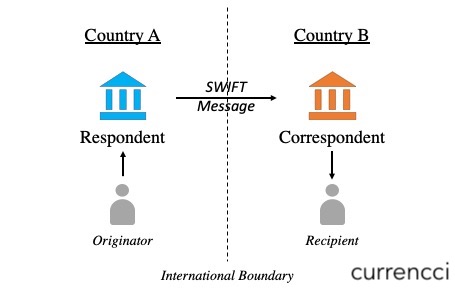

International wires are settled via correspondent banking relationships. The operation is simple. First, the originator will approach their bank for a wire. The originator bank deducts the funds from the originator’s account (plus fees), and sends a wire communication through the SWIFT network to the recipient’s bank. This communication directs transfer of the same amount from the originator bank’s account at the recipient bank to the recipient’s account at the recipient bank. Aggregate fund balances between banks are settled periodically, through transfers at federal banks or via cash.

Figure 3: Overview of how SWIFT messages enable inter-country communications between issuers by enabling correspondent banking.

Figure 3: Overview of how SWIFT messages enable inter-country communications between issuers by enabling correspondent banking.

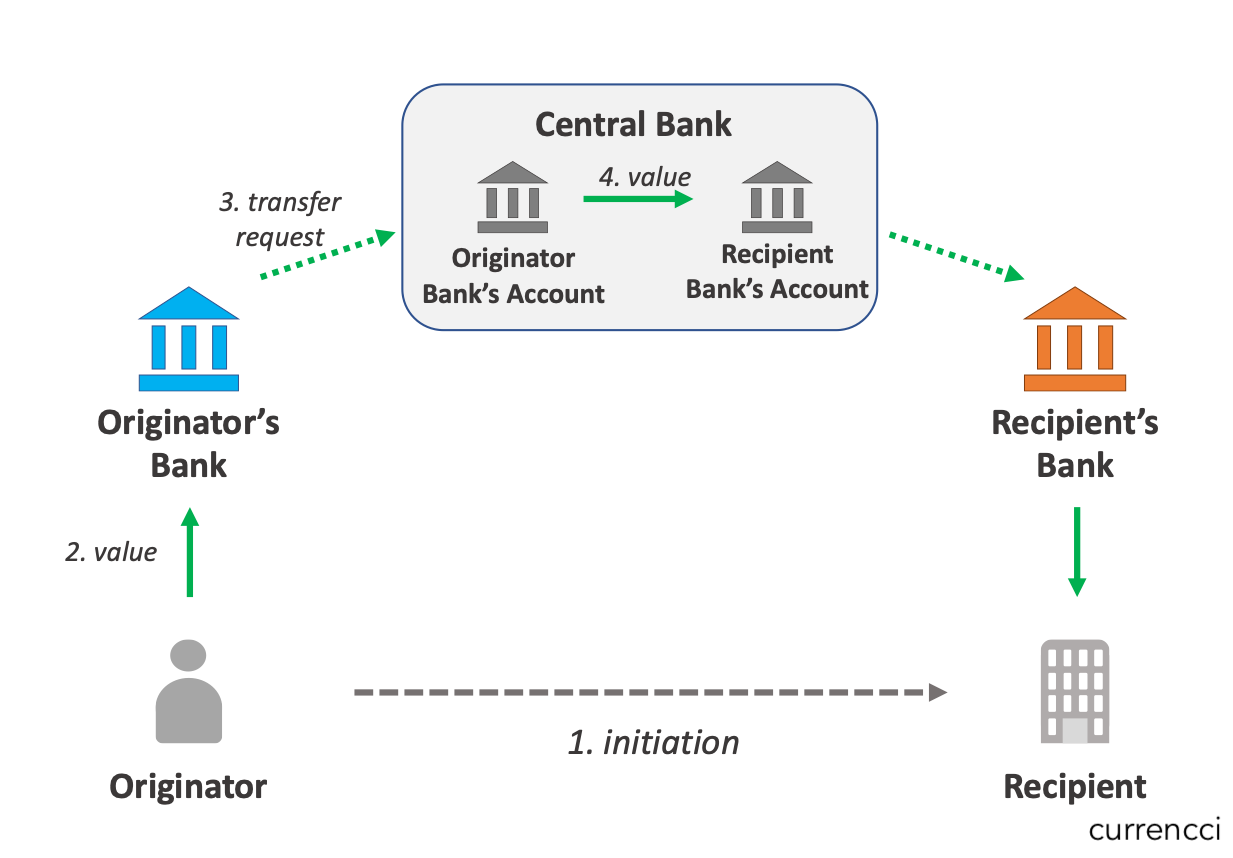

Domestic wires are centralized. The United States FedWire system, run by the federal government, offers a typical example: domestic banks each set up an account at the Federal Reserve. Similar to an international wire, originator’s funds are deducted and a communication sent to the recipient’s bank. Unlike international wires, once the message is approved, value is transferred between the two banks’ accounts at the Federal Reserve.

Figure 4: Simple domestic wire diagram. Payment is initiated by the originator, who then instructs their bank to transfer funds. Rather than directly transfer funds with the recipient’s Bank, funds are transferred between respective banks’ accounts held with the Central Bank.

Figure 4: Simple domestic wire diagram. Payment is initiated by the originator, who then instructs their bank to transfer funds. Rather than directly transfer funds with the recipient’s Bank, funds are transferred between respective banks’ accounts held with the Central Bank.

In both systems, the recipient’s bank credits the recipient’s account before the funds are moved between the originating and recipient banks. Settlement between the banks can take place from a few hours to as much as a full day past the wire being transmitted. The result is a small degree of uncertainty due to the delay. For the most part this risk is mitigated by a basic governance framework enforcing ‘good’ participant behavior. Because Wire Transfer Networks are limited to only known financial institutions, participant disputes are rare and generally resolved quickly and without confusion or major loss.

An extra hurdle in both international and domestic systems is that linking messages with fund transfers is only partially automated. Manual input is required to authorize, receive, interpret, verify, and implement wire transfers. The industry now employs thousands of ‘wire transfer specialists’ to perform these operations, which have grown into a cumulatively massive cost center for the financial industry. These costs are made up for by high fees, but not so much so to make wires a major revenue driver of any bank’s business.

Technically clunky, wire transfers are preferred amongst existing options from a business perspective. Their manual nature results in high costs both to send (~$25 USD domestic, ~$40 USD international) and receive (free to ~$20 USD) but guarantees a high level of security and reliability. Further, nearly all wire transfers are completed within a day. The resulting security and speed has resulted in wires being used most often for large value transfers, particularly commercial payments.

The largest limitation of wire transfers is how little information they contain, due to their legacy infrastructure. Wire messages are bound by rigid formats designed decades ago and contain only basic payment details in plaintext format. The restricted information hamstrings innovation - only so much can be built off of a few thousand characters of ASCII text. Further, limited context hampers remittances and payment reconciliation as well as introduces serious compliance risk.

Though standards bodies and network operators - primarily SWIFT - have in recent years encouraged new messaging formats, these efforts have mostly failed from a lack of centralized power to force participants to upgrade technical systems. As a result, Wire Transfer Networks are stuck with attempting small incremental upgrades while maintaining backwards compatibility. The end result are payment messages containing only essential details and lacking important contextual information useful for reconciliation as well as compliance purposes.

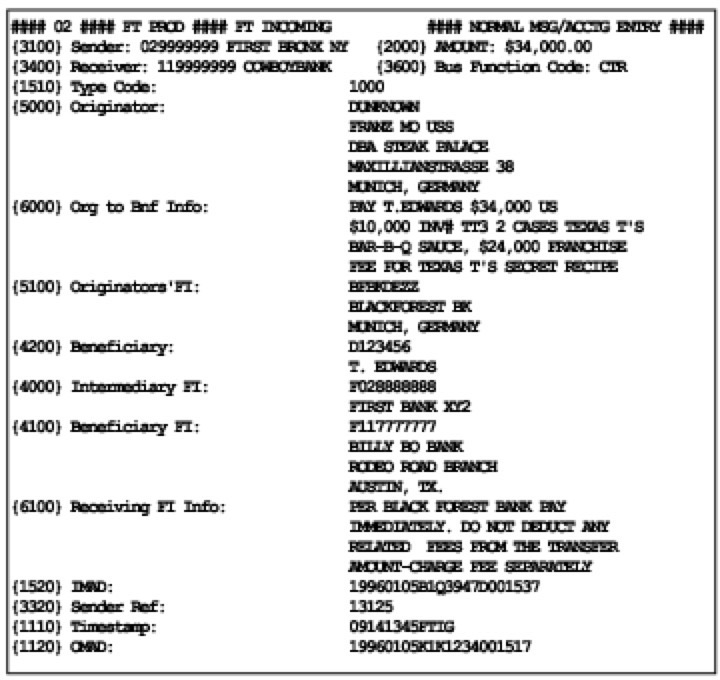

Figure 5: Example of a typical Wire Transfer message. Note the limited contextual information, particularly around originator and recipient. Taken from Columbia University.

Figure 5: Example of a typical Wire Transfer message. Note the limited contextual information, particularly around originator and recipient. Taken from Columbia University.

Between the high costs, manual labor, inability to change, and limited data transferred, wire transfers play an outdated and fading role in a world requiring cheaper, automated, and data rich solutions.

global card networks

Cash may now be king, but Payment Cards may soon usurp the throne. Nearly everyone is familiar with these small plastic rectangles enabling easy electronic payments at physical and online merchants around the globe. Ubiquitous amongst consumers, businesses are less likely to use cards to pay one another.

Like Wire Transfer Networks, the Global Card Networks offer a version of the best of yesterday - generally fast, yet less secure, unsophisticated technologically, and expensive. Private, international digital networks owned and operated by commercial companies, Global Card Networks enable consumers to make a purchase at any participating merchant. Their easily accessible networks possess the world’s most sophisticated governance frameworks, though - like wires - their legacy infrastructure and business model hinders their adaptability to changing requirements.

The basic model of Global Card Networks is genius. Two major variants exist: the three party model and the four-party-model.

The three party model (also known as the ‘go-it-alone’ or ‘closed-loop’ model) consists of a single entity both managing and operating a payments network. Well-known examples include American Express and Discover. Participants must first establish a direct relationship with the network owner in order to transact with one another. For each transaction the network operator simply transfers funds from the originator’s account to the recipient’s. While the centralization offered by the three party model allows for greater technological and procedural flexibility, growth and size are limited by the requirement of every participant to maintain a relationship with the operator.

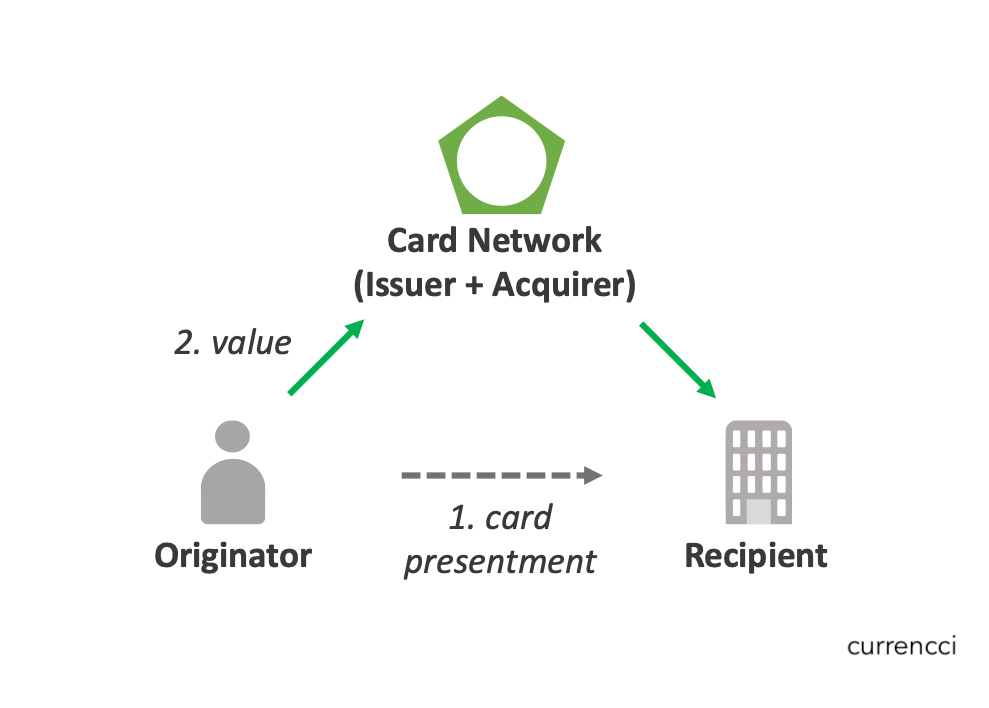

Figure 6: Basic overview of the three party model. Once the originator presents their card information to the recipient, value is transferred between the two parties by the Card Network.

Figure 6: Basic overview of the three party model. Once the originator presents their card information to the recipient, value is transferred between the two parties by the Card Network.

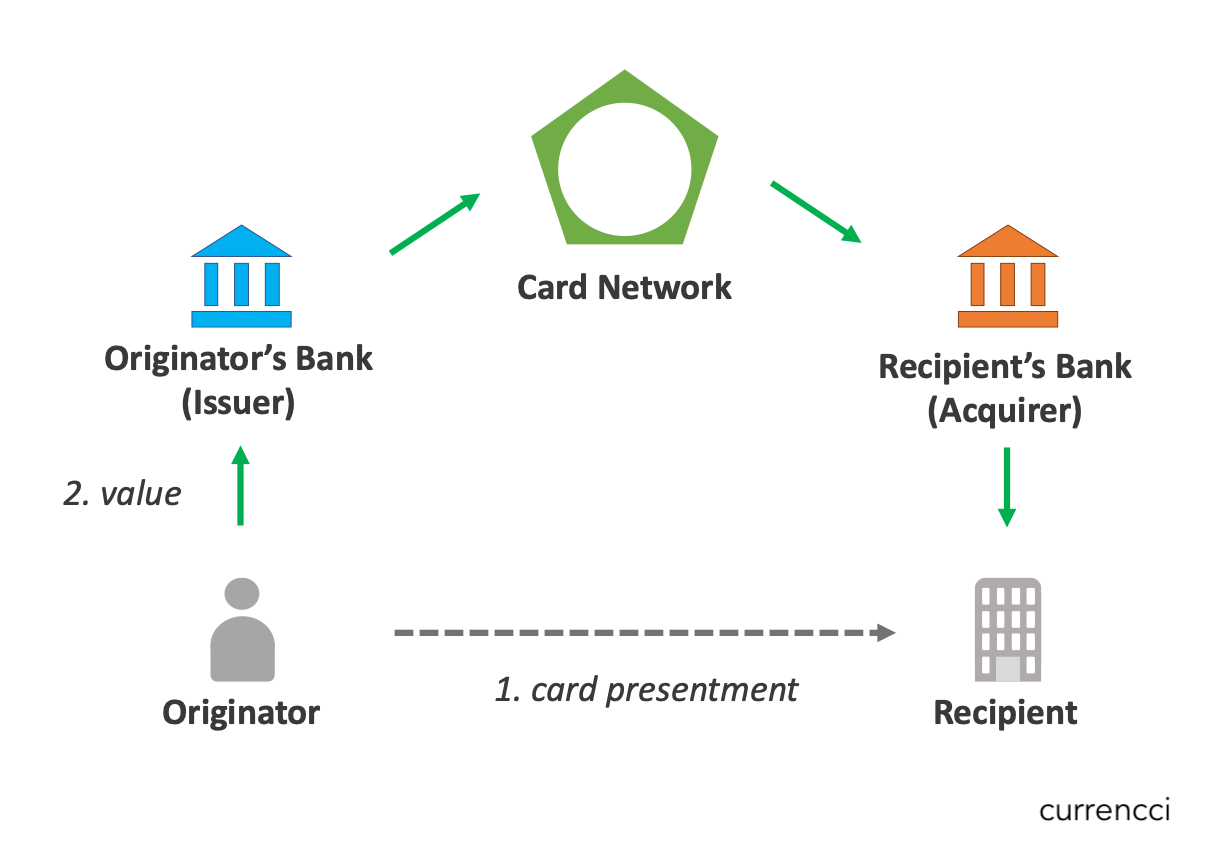

The four party model (i.e. the ‘open-loop’ model) consists of a single entity managing and partly operating a payments network, while leaving a significant remainder of the operations to member participants. Familiar examples of the four party model include Mastercard and Visa. Confusingly, there are five participants to a payment in the four party model: (i) the originator; (ii) the originator’s bank, called the issuer; (iii) the network operator, called the scheme; (iv) the recipient’s bank, called the acquirer; and, (v) the recipient. To function, the scheme recruits issuers and acquirers to offer operating services on its network in order to earn a commission. Issuers provide payment cards and associated payment accounts to originators, while acquirers provide payment receiving technology and relevant accounts to recipients. While decentralization to hundreds - if not thousands - of issuers and acquirers slows network agility to change, its open model offers immense scale.

Figure 7: Diagram of typical card network payment under the four-party model. Originator and recipient accounts are now held at distinct financial institutions, and value is transferred between them by the Card Network.

Figure 7: Diagram of typical card network payment under the four-party model. Originator and recipient accounts are now held at distinct financial institutions, and value is transferred between them by the Card Network.

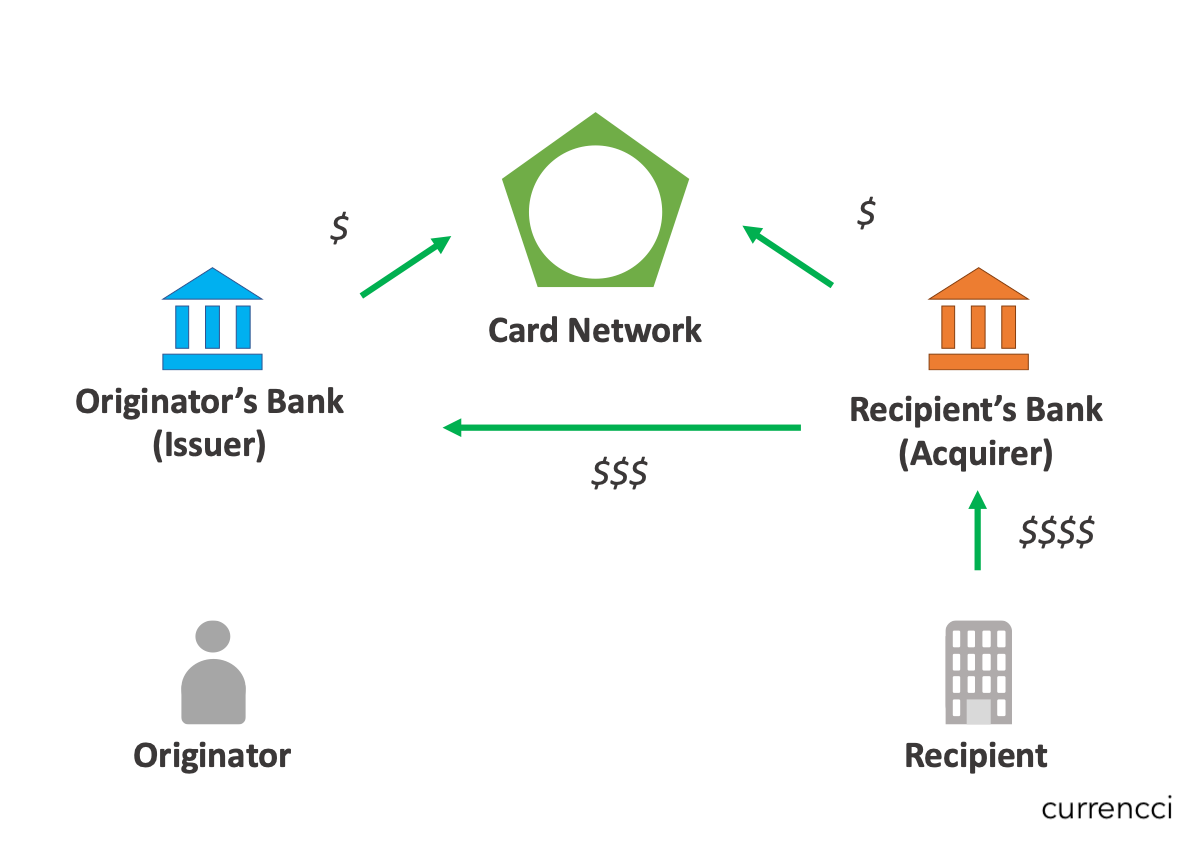

The economics of the Global Card Networks are conceptually simple. Recipient participants pay the operators a combination of a fixed fee for each transaction, accompanied by a variable fee tied to its value, which get divided amongst the participants. Though the fees are set at basis point levels, the scale of these payment networks provides enormous revenue for the operators (as well as issuers and acquirers in the four party model). Recipient payment for transactions is essential - recipients are the ones in need of and prioritize the financial value, whereas the originator cares mostly about the good or service being delivered by the recipient. As such all fees are collected from recipients and the payment service is free to originators, albeit the price may implicitly contain the fee. Though low value individually, these fees generate massive revenues for Card Networks and the participating banks in the aggregate - all stemming from the recipients who are most commonly merchants (for example, a typical credit card transaction may cost the recipient 2-3% of the overall amount paid, though this pricing varies according a boggling array of factors such as card type, purchase channel, and more).

Figure 8: Simplified diagram of how fees are generated and divided amongst the four-party network. The recipient pays fees to their bank for the right to accept card payments, while the recipient’s bank spreads a portion of these fees throughout the remaining facilitating parties.

Figure 8: Simplified diagram of how fees are generated and divided amongst the four-party network. The recipient pays fees to their bank for the right to accept card payments, while the recipient’s bank spreads a portion of these fees throughout the remaining facilitating parties.

Try as they might to lobby (regulators and/or schemes) for fee reductions or the ability to surcharge originators, merchant organizations have made little headway as their issue is with the fundamental business model of the network, which simply could not sustain itself with originator paid fees. In many jurisdictions where merchants can add customer surcharges, including parts of the US and European countries like Belgium, they have overwhelmingly decided not to. Elsewhere, in markets like Australia, merchant surcharging led to additional charges atop the networks’ fees, damaging consumer trust, prompting regulation, and ultimately leading to ‘fee-free’ consumer campaigns with consumers flocking to merchants without added surcharges (i.e. baked in pricing for card purchases, consumers in these markets are not giving up their cards). To no-one’s surprise, consumers are unwilling to pay for what was once free and instead take their business elsewhere.

It is worth noting here that Card Network fees are objectively expensive, costing anywhere from 1% to 3% of a transaction’s total value. The debate of whether these prices are appropriate can fill volumes and will not be covered here, but recognize that in markets where card fees are regulated the Card Networks’ service levels do not appear very much affected other than fewer cardholder incentives (e.g. cash back, points, etc.). One could make the argument that higher prices were at one time justified in an earlier era, but the digitization of payment networks has reduced costs while fees remained fixed.

The largest contributing factor to the Card Networks’ success is their robust governance, guaranteeing a safe ‘payment ecosystem’. The platforms have extremely low barriers to entry to participate, enabling payments between essentially all willing individuals and businesses on the planet. The mortar holding this together is a shared trust, reliance, and adherence to the Card Network’s rules which are rigorously enforced not only by the Card Networks, but participants themselves. Distributed liability ensures parties work together to self-police, dispute procedures facilitate issue resolution, and the Networks provide final rulings to the few escalated items.

Like the Wire Transfer Networks, the Card Networks main limitation is their technological infrastructure. Their distributed operations that enable their massive scale also hamstrings their ability to quickly evolve and adapt themselves. Aside from the massive operational and business challenges of encouraging bank and merchant participants to upgrade their digital systems, Networks must propagate new physical hardware throughout the tens of millions of originators (cards) and recipients (terminals) to effect substantial upgrades. Backwards compatibility to accommodate these oftentimes aged hardware further confounds innovation. It must be noted however that this deliberate pace ensures extremely stable and constant international performance. This reliability cannot be understated as without trust and scale, the systems could not exist.

Two main issues emerge from this antiquated technology: the limited data contained in payment messages, and the speed of payment.

The Card Network’s antique technology means their payment messages are stuck containing limited data in a digital landscape of ever-increasing sophistication. The basic payments standard for the Card Networks was developed in 1987 - ISO 8583, with major updates in 1993 and 2001. As expected the standard is antiquated and only allows for transmitting basic payment details, such as amount, originator, recipient, and online versus in-store. Like wires, card payments are subsequently hamstrung for modern innovation. For instance - it is extremely unlikely current systems will ever be able to technically display rich information on an individual purchase on a cardholder’s bank statement, like items purchased, store address, and more. This is not to say the Card Networks and participants are working diligently to innovate and supplement messages however possible, but their pace will remain slow into the near to mid-term as they look to complement existing payment messages rather than overhaul them outright.

The other major limitation of the Card Networks is their speed. A payment made between parties can take days from initial authorization to final settlement. The long delay introduces considerable risk to all parties: the information is exposed to possible interception for a longer period and the available funds in the originating account may be removed (though most banks have various methods to minimize this latter risk). Further, the recipient has delayed access to funds, reducing their working capital.

Like the Wire Transfer Networks, Card Networks offer a dependable and secure service which is growing rapidly outdated as the new technologies emerge. High prices and increasingly sophisticated digital needs are increasing demand for alternatives, yet the Card Networks’ massive scale poses a significant challenge to new entrants.

automated clearing houses

Think of your paycheck - you likely weren’t paid in cash or a check. Instead, you were paid through direct deposit through an ‘ACH’ payment. While consumer use is less common, ACH is how businesses make the vast majority of their payments to one another, making it responsible for moving the most dollars of any payment rail.

Automated Clearing House (ACH) systems are the workhorses of the payments industry - underrated by most yet responsible for transmitting the overwhelming majority of payments dollar volume globally. Though built as they are today in the 1970s, their lineage can be directly traced to the foundation of modern banking in medieval Europe. Like the other major payments networks ACH systems enjoy massive scale and are critical to the global financial system, yet are hobbled by antiquated infrastructure and an inability to evolve.

ACH systems grew out of necessity. Clearing Houses were originally organized to facilitate transfers between banks and this service gradually expanded to enable account holders to transact with one another. This system coalesced into the use of checks - originator supplied paper slips authorizing transfer of funds from the originator’s bank account to the recipients. The logistical complexity and spiraling costs of facilitating transfers between any two given banks grew so convoluted that in the late 1950’s the banking industry in the UK collectively established the world’s first Automated Clearing House (ACH) in 1968, effectively streamlining the process through digitization. Similar networks quickly emerged in other markets. Over time the use of paper checks has slowly diminished while use of their electronic counterparts has steadily grown.

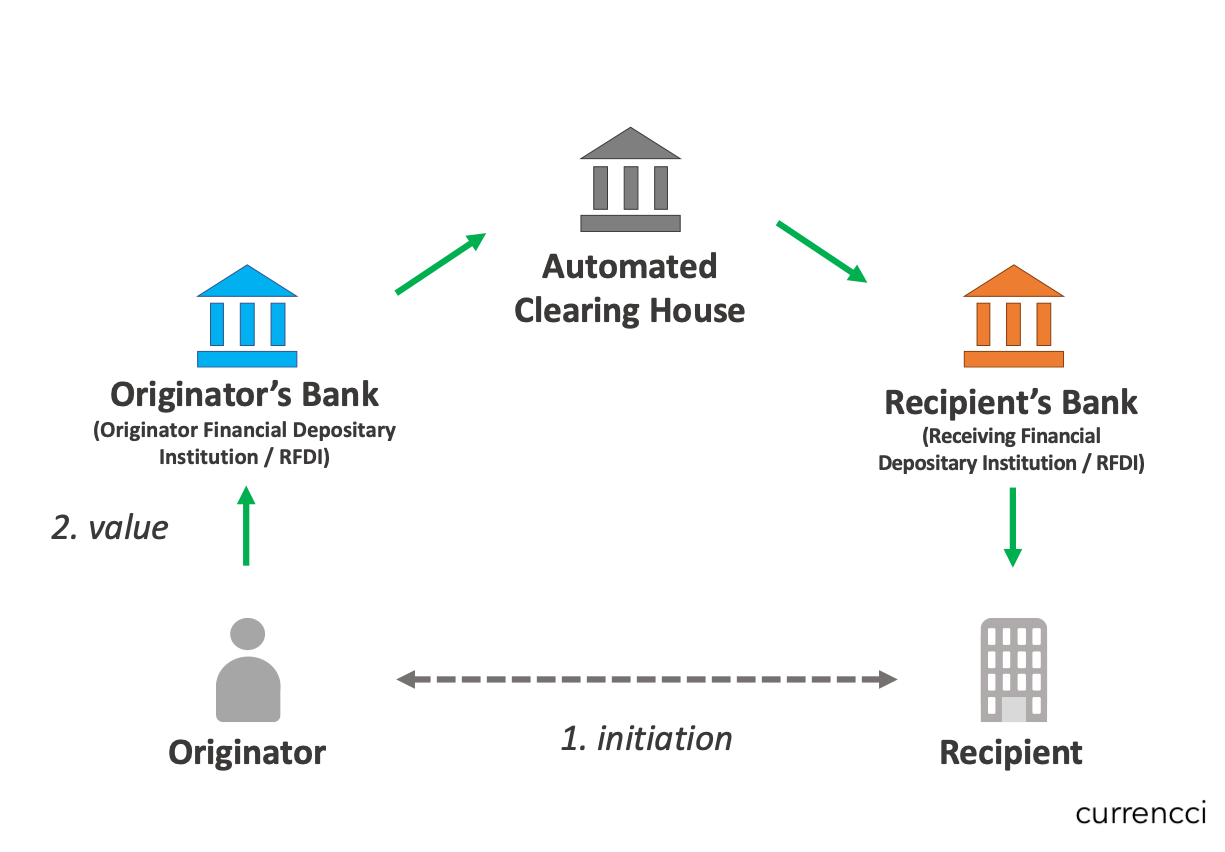

Figure 9: Simplified diagram of ACH transactions. The payment may be initiated by either the originator or the recipient.

Figure 9: Simplified diagram of ACH transactions. The payment may be initiated by either the originator or the recipient.

Their essential role in enabling bank-to-bank interactions - and thereby general economic activity - has caused ACH systems to develop on a country by country basis. Two main operating models have emerged. In most markets, national security concerns have led to federally run systems. Elsewhere, powerful banking associations established independent non-profit ACH operators to operate in close partnership with the federal government. Little differentiates these systems other than association-managed systems are more often accused of discriminatory business practices by smaller banks or non-association members. A function of ACH Networks’ domestic focus is that they cannot facilitate international payments, which are instead routed over Wire Transfer Networks.

A history of underinvestment has left modern ACH systems woefully out of date and increasingly ill-suited to modern needs. Most obvious is the limited data accompanying payments. Like the other major networks discussed so far, ACH payments generally rely upon aged, non-dynamic standards which fail to provide more than the essential payment details. In turn, poor data quality hampers innovation, ancillary services, and integration with modern systems all while increasing compliance risk. Though the need for a technological renovation is clear, updating ACH standards is difficult as bank participants are loath to update their core digital infrastructure. The added tolerance of ‘good-enough’ data only adds to this inertia.

Just as crippling to ACH systems is their bureaucratic stagnancy, epitomized by the extensive time required to complete an ACH payment. In the United States for instance, a payment can take three to five days from origination to completion. Appallingly, this delay is entirely artificial. Historically, infrastructure operation was limited to banking hours during the workweek, and transactions were processed in aggregated batches sent at the end of the day from the bank to the ACH. Payments were then processed by the ACH in a similar manner before being forwarded to the recipient banks. Batch processing meant an ACH payment submitted after the cutoff time on a Friday wouldn’t be forwarded to the ACH Network until the end of the day Monday. Though systems evolved to handle always-live real time operation, arbitrary cutoff times were kept in place. Ultimately the pressure to evolve has led to recent procedural updates resulting in ‘next day’ and ‘same day’ ACH payments.

These updates to ACH are limited to how quickly the payments complete. The improvement boils down to the addition of more batch file ‘processing windows’ which decrease the time required between payment initiation and completion. Though these speedier ACH options are slightly more expensive than traditional ACH and hardly marketed, they are rapidly growing in popularity for all types of ACH payments. That this simple system adjustment has been introduced nearly fifty years after the system was introduced speaks volumes on how stubborn the payment channel is to change.

In spite of their technological drawbacks, ACH systems are wildly successful. Why? Their simplicity in enabling interbank account-to-account transfers at extremely low cost. Governments worldwide have implemented legislation mandating ACH networks to operate at cost, fixing prices at lower rates (e.g. in the United States a typical ACH transaction costs ~$0.25). Fixed pricing with ACH systems - contrary to the variable pricing of other payment networks - makes them the default choice for larger and commercial payments.

In addition to the low cost, ACH networks attract large value payments due to their low-risk for payment originators, a function of their speed and governance. The delay of ACH processing means an originator can cancel a payment after it is initiated. Originators can leverage this to their advantage by initiating a payment, but cancelling if a promised good or service is faulty. Originators also enjoy a small, but valuable window of ‘float’ on funds before they are formally transferred. Of course all of these are negatives for payment recipients who are threatened with unfair payment cancellations and delays. ACH Network governance also reduces risk. Established, tested, and participant enforced rules ensures generally ‘good’ behavior.

More so than anything else, ACH Networks stand out amongst the other major networks for allowing both ‘push’ and ‘pull’ payments. We haven’t reviewed this concept so far, but nearly every other payment network allows for only one payment form or the other. That ACH Networks provide both allows for tremendous utility, which is another reason why ACH Networks are preferred for commercial transactions.

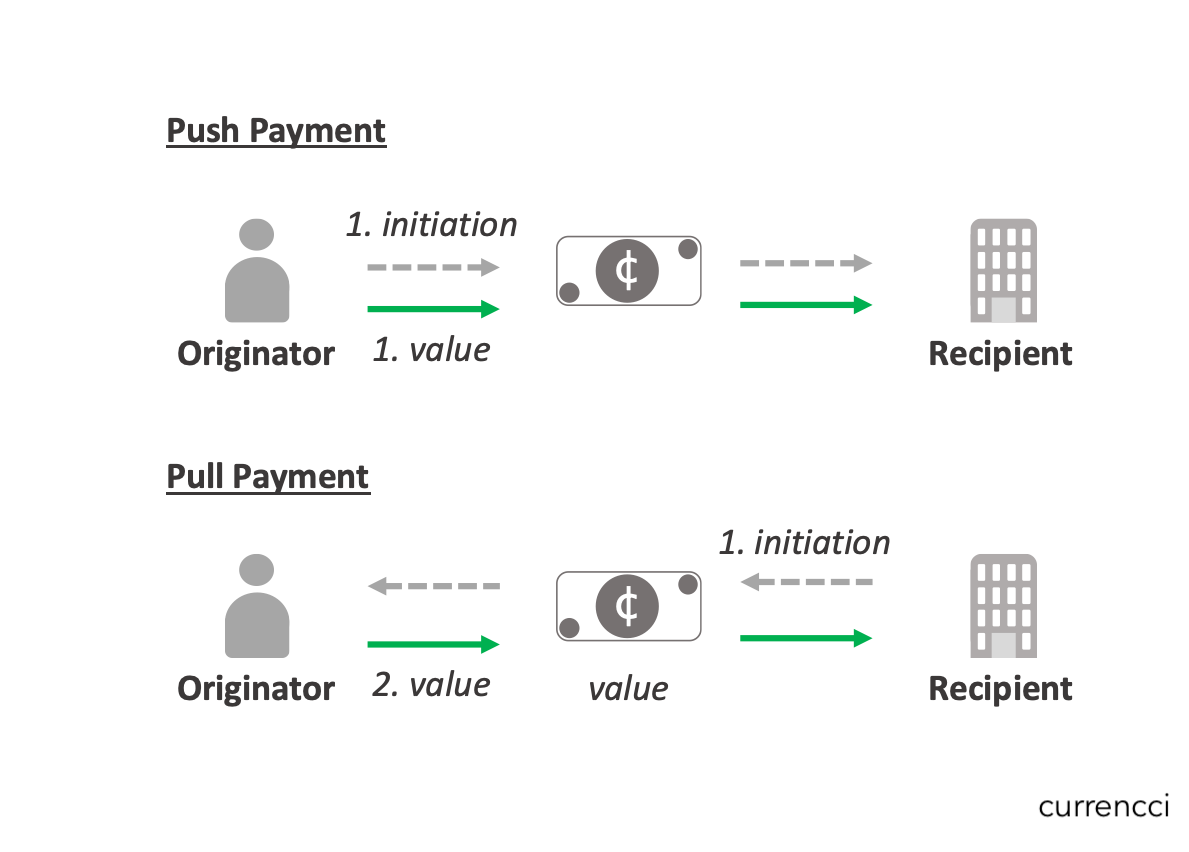

The concept of each payment type is simple once learned. ‘Push’ payments are those which an originator initiates the payment to the recipient, ‘pushing’ funds from their account. Wires and cash payments are classic examples of push payments. They advantage originators, who maintain unilateral control over all aspects of the payment, from amount to timing to more. Push payment recipients can only wait for such payments to come through. ‘Pull’ payments are just the opposite - the recipient initiates the transaction and extracts funds from the originator’s account. To avoid wanton fraud, pull payments require originator pre-authorization, either on an ad-hoc or standing basis. Card payments are the most common example, in which a merchant recipient uses the consumer’s card details to authenticate a pull of funds from the originator’s account. Contrary to push payments, pull payments favor recipients by granting them control over payment characteristics including amount and so on.

Figure 10: Push versus Pull payments.

Figure 10: Push versus Pull payments.

Access to both push and pull payments enables greater flexibility on the ACH Network than other network types. Most notably, commercial entities leverage this the most to arrange deals between otherwise suspicious originators or recipients by shifting transaction power.

The low cost and flexibility of ACH Networks have sustained their position as the foremost method of commercial payments, yet their technological limitations are growing more apparent each day. Though helpful, remedial steps to improve the networks’ most obvious pain points fall short of fully meeting modern needs.

alternative payment networks

Ever heard of Alipay, WeChat Pay, or MPESA? These are firms providing their own proprietary payment networks, independent of all others. Don’t worry if you haven’t heard of an Alternative Payment Network, most are domestic to their country of origin, and there aren’t many. That said, where successful they are massive.

Finally there are the new payment systems awkwardly labelled “Alternative Payments Networks,” which include Alipay, WeChat Pay, and MPESA. (Editors Note: I leave out so-called []‘crypto-currencies’](https://currencci.com/post/210201_cryptomad/), as these have failed to result in any widely used mechanism for transferring wealth for any practical purposes. Rather, they seem to represent a value storage system, though the long term viability appears doubtful. We also leave out apps like Venmo, which only provide overlays to existing payment rails (i.e. ACH) as opposed to truly original payment systems.) These networks have emerged and rapidly grown over the past decade, threatening established payment methods where they’ve developed. Generally built by non-traditional players, their unique features offer valuable inspiration.

The largest Alternative Payment Networks share similar origin stories. First, each grew out of serving a niche need in an underserved market. These Networks knew their participants well, and weren’t threatened by incumbent competition. Further, their customers were eager to find a solution to their needs and were willing to try something new. For instance, Alipay emerged out of a need to establish trust between online buyers, while MPESA grew out of a quasi-remittance system for transferring funds between city and urban populations. Second, each of the solutions emerged in both cash-heavy and generally less developed economies. Potential customers were eager to ditch the physical risks of cash, while traditional players accustomed to higher fees were unwilling to operate with tighter margins, further reducing competition.

Alternative Payment Networks also share tremendous variety in how they function, though the overall concept is fairly constant in that each relies on an entirely proprietary network. Advances in computing capability have enabled single players to perform all the functions of value storage, manipulation, and transfer between parties in a method similar to the ‘three party network’ described in the earlier Card Networks section, but with one crucial difference - the barrier to participate for both originators and recipients is only a mobile phone rather than specialized physical hardware (i.e. card and reader). As a result, Alternative Payment Networks enjoy the benefits of centralization paired with the ability to quickly innovate, iterate, and implement new features and systems. Case in point - today’s major Alternative Payment Networks offer nearly instantaneous transfers and settlements, and retain the technical infrastructure to carry as much accompanying payment data as needed. This technological ability is key to their success thus far and offers them tremendous advantage over traditional payments systems.

The payments themselves which are routed through Alternative Payment Networks are ironically given limited attention. These networks were built to solve the needs of their participants, which weren’t necessarily the payments themselves. MPESA enables secure remittances from urban areas to rural ones, Alipay removes risk, and WeChat facilitates social interactions. The information that traditional industry would consider most important is thus de-prioritized in favor of solving the actual need. This emphasis drives the most shocking innovation of the Alternative Payment Networks - the transactions are essentially provided for free! Payment transmission is likely a cost-center at most of the Alternative Payments Networks while real revenues are derived from surrounding services. Like sleeping giants, the Alternative Payment Networks have the organizational and technical ability to quickly concentrate their payments focus - and directly attack traditional players - should their strategic aim focus.

Despite this superficially advantageous position however, Alternative Payment Networks face massive hurdles in truly challenging the traditional payments and financial industries. Like their legacy counterparts, the greatest strength of the Alternative Payment Networks is inseparably paired with their greatest weakness - their proprietary nature leads to poor cross-compatibility with other payments networks. Participants extracting their money from these closed ecosystems face hefty fees and procedural hurdles - recall their revenues are derived from services provided within their closed ecosystems. Not only does this frustrate participants, but also - and far more significant - this closed nature disincentivizes engagement with traditional players, severely limiting the ability for Alternative Payment Networks to expand into traditional commercial flows as well as internationally.

Alternative Payment Systems also face larger governance and regulatory hurdles. Whereas traditional players have a long history complying with financial legislation and possess strong regulatory relationships, Alternative Payment Networks are generally naive to payments regulation. Increased regulatory oversight over the past decade further pressures new entrants, and their novel structures threaten unfamiliar regulators. Finally, their lack of strong and time-tested dispute resolution procedures cause participant friction and dissatisfaction.

Growing pains aside, the Alternative Payment Networks have emerged as powerful contenders to the traditional payment networks through a combination of technological prowess and an unrelenting focus on solving customer needs. Their novel operating and business models offer valuable lessons and insight towards building superior payments networks. Though quickly expanding in their home markets, their future as truly holistic and international payments systems remains doubtful due to their closed nature.

where we are today

We now conclude our tour on modern payment channels. I’ve covered the major international (Cash, Wire Transfer Networks, Global Card Networks) and domestic (ACH, Alternative Payments) systems, and reviewed how each possesses numerous advantages and trade-offs. Summarizing these features brings us back to the table at the top of this essay:

Table 1: Major payment channels overview, showcasing relative characteristics

These differences are no accident - each payment channel emerged to address peculiar needs and the market has grown to leverage each optimally. For instance, consumer-to-business payments tend towards Global Card Networks, while international commercial payments rely almost exclusively on wires. Entire sub-industries have evolved to help consumers and businesses alike optimize their use of payment channels and do their best to reconcile their transactions between these disparate networks.

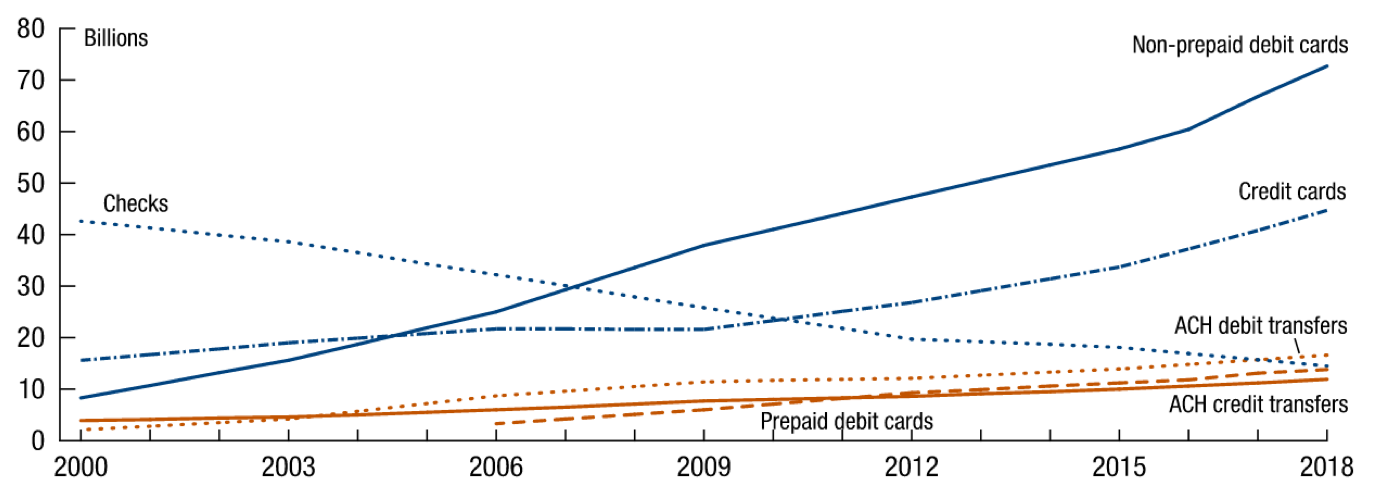

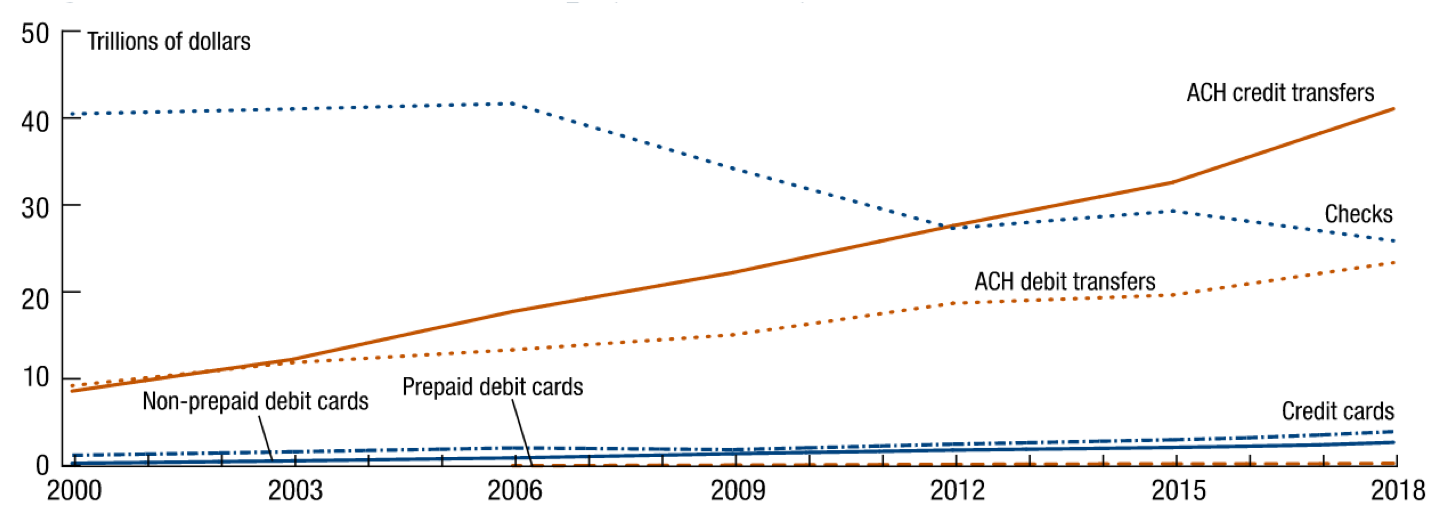

Figure 11a and 11b: Comparison between overall US volumes of Card Network payments versus ACH Network payments (total payment count above, dollar volume below). Reliable data showing each payment channel was unavailable, but this study provides a rough sense of the scale of these major payment networks. Wires would be lowest transaction number with second highest volume, cash would be highest transaction amount with moderate volume, and Alternative Payment Networks would be moderate in each. Taken from the US Federal Reserve.

Figure 11a and 11b: Comparison between overall US volumes of Card Network payments versus ACH Network payments (total payment count above, dollar volume below). Reliable data showing each payment channel was unavailable, but this study provides a rough sense of the scale of these major payment networks. Wires would be lowest transaction number with second highest volume, cash would be highest transaction amount with moderate volume, and Alternative Payment Networks would be moderate in each. Taken from the US Federal Reserve.

At first glance, the number and variety of payment networks available today offer an attractive argument that the payments industry is healthy, resilient and positioned for growth. Market forces have naturally uncovered and filled gaps in cash’s baseline offering. Consumers have options, and competition appears to encourage innovation and efficient pricing.

Our informed inspection is not so kind. Most major payment networks today run on decrepit infrastructure, whereas the only modern systems - Alternative Payment Networks - are built by industry outsiders and not yet suitable for serious consumer or commercial flows. Functionality has remained constant while technology and needs have drastically changed. Businesses and consumers alike need rich data, global payments, instant transmission, all with low risk and lower cost. Globalization and digitization increase this pressure each day and existing payment networks all appear incapable to meet this new environment head-on.

Fortunately for us, a new type of payment network called Real Time Payments (RTP) is emerging to address modern needs while retaining the best aspects of old systems. Now armed with an understanding of today’s dominant payments networks, we will explore the system poised to disrupt the industry and propel payments into a new era in Part II.

I welcome your feedback. Please don’t hesitate to reach out through the contact section of the website if you would like to discuss, comment, or have any suggested edits.

[1] A good but unnecessarily long review of multi-sided platforms is the book: Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms by Evans and Schmalensee

[2] ECB report examines the costs of making payments in the European Union. European Central Bank, October 1, 2012.