'weird' finance

From time immemorial financial independence has equated individual freedom. While the stores of value themselves vary – substitute goats for a house – access to the basic mechanisms for assessing, holding, and transferring them has separated the have’s versus the have-not’s.

Today, access to the modern financial system is now perceived as a fundamental right and championed under the cause of ‘financial inclusion’, which aims to bring everyone on the planet into its network. Further, the concurrent rise of technology and globalization has opened up previously underserved markets. This confluence has led to a recent wave of both startups and big businesses alike touting a slew of ‘alternative’ services to the ‘underbanked’, including ‘alternative credit scoring’, ‘alternative payments’ and more. If all continues, it is reasonable to expect in the near future everyone on the planet will be served by some form of digital financial service.

Despite their diversity, the basic premise of almost all of these new ‘alternative’ services focus on novel delivery mechanisms for traditional financial services. In the rush to tap new markets and segments, nobody seems to have questioned the basic premise of ‘are financial needs universal,’ or even more important – ‘do financial solutions cater to these needs’?

In a 2010 paper titled “The Weirdest People in the World?” behavioral scientists questioned whether the research and findings of Psychology’s past hundred years were valid characterizations of human nature. The reason – the field’s foundations were built upon research of almost exclusively ‘Westernized, Educated people from Industrialized, Rich Democracies’. Whereas Natural Sciences inherently offer absolute results (e.g. gravity), sciences built on extracting laws in human behavior offer only approximate answers. It turns out universalities of human nature are difficult to extract from studying only Ivy League psychology undergraduates.

In the same way, the products and services provided by the financial industry may not be as universally applicable as those industries offering more tangible goods. While the intentions of financial inclusion efforts are certainly well-founded, is access to a financial system optimized for the middle- and upper-class consumers of the developed world beneficial to a rickshaw driver in Bangladesh? Is it for a poor member of a rich society? In fact, are these systems even appropriate for anyone?

characterizing basic economic needs

The field of Economics, the academic bedrock of the financial industry, had its own Reformation instigated by scientists including Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, and Richard Thaler in the 1970’s. These thinkers argued humans were not always the rational decision makers portrayed by traditional Economics and were instead irrational players who oftentimes acted against their own self-interest. Understanding this required a level of nuance into human context and basics needs. Dubbed ‘Behavioral Economics’ the field seeks to chart out the fundamental truths of economic decision making and has already introduced many valuable theories, including Prospect and Nudge theories.[1]

As digital financial services have exploded in popularity, insights from behavioral economics have percolated into the business landscape, mixing democratization of powerful financial tools with cleverly designed ‘nudges’ aimed at influencing consumer actions. The result is absolute technical financial independence overlaid with an ‘optimized’ user interface, wherein a high school graduate now has the same tools available to themselves as a seasoned wealth manager, overlaid with a bubbly interface encouraging ’engagement'.

Ironically, one of the most notable ways behavioral economics has infiltrated industry are the efforts to eliminate the human element entirely. Vanguard, starting from an undersubscribed raise of $11 million, has become a behemoth managing USD $6.2 Trillion by exorcising speculation via ‘boring’ indexes. Newer firms championing these values include Betterment and Wealthfront, which offer snazzy graphics, automatic deposits, and more all to counter-intuitively encourage minimal levels of consumer engagement.

The other main class of services inspired by behavioral economics aim to manipulate users through the use of ‘nudges.’ One popular example is the PayPal owned mobile app Venmo, which facilitates person to person payments. Upon opening the app, users are presented with a list of recent transactions amongst friends and strangers accompanied by jaunty, emoji-ridden memo lines (“tacos + beers”), welcoming the user to wade in and join the party.

Acknowledging and regardless of the potential “weird”-ness of these studies, behavioral economics appears to be ever-so-slowly transforming financial products into ones more relevant for the average human. Many of the field’s teachings clearly have application towards financial products, for instance:

- Choice Overload: We are prone to inaction when presented with many options (e.g. money management)

- Negative Feedback: We fail to recognize the outcome of not doing something (re: masks during the COVID pandemic) (e.g. money invested, not spent)

- Availability Heuristic: We defer to and trust anecdotes over data (e.g. investing)

- Inertia: We are more likely to stick with the default than enact change (e.g. opt-in 401k)

- Overconfidence Effect: We overestimate our own performance even when given evidence (e.g. finding a ‘deal’ for a large purchase)

- Hedonic Adaptation: Our general happiness rapidly reverts to our personal mean when circumstances change

- Loss Aversion: We prefer avoiding loss over incremental gain (e.g. spending decisions)

- and so on…

Taken together, the science is increasingly confirming that yes, economic needs and behaviors are indeed universal and baked into us at a biological level. Only recently have scientists begun publishing more earnestly on economic behaviors within the broader plant and animal kingdoms, reinforcing the concept that economic instincts are as fundamental as thirst.

The problem for homo sapiens is our modern financial needs don’t perfectly align with behaviors evolved in the wild. In the past, this issue was resolved through expertise – savvy finance professionals (generally) knew better by the time they started making complex financial manipulations. Now however, newly empowered masses have access to the same tools as professionals while remaining as susceptible as they always were.

Decision makers in financial services are increasingly aware of this fact and to build around it by creating products which (i) define the individual’s specific needs; and (ii) maximize those by correcting or encouraging the individual’s economic impulses (known in behavioral economic parlance as ‘nudges’). Leveraging known influences at scale promises immense benefit - individuals and societies could reap extraordinary efficiencies and eliminate needless economic pain. Just imagine if everyone spent responsibly, got the best deal, and saved what was needed.

reality check

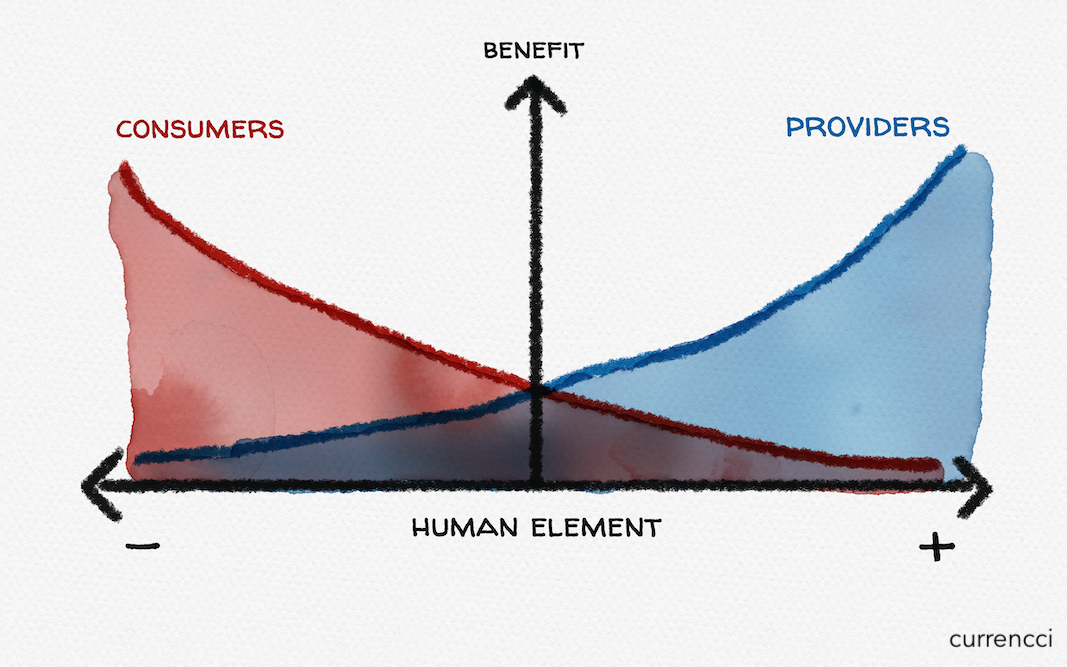

Of course, this vision disintegrates in practice as decision-makers in financial services are not benevolent, neutral operators. Behavioral economics has granted them both the power and responsibility for actively choosing where to incent behaviors, and who reaps the benefit. As one would expect, behavioral economics shows us those in power are inclined to skew systems to their own benefit.

The business world has pounced at the opportunity to ‘nudge’ (i.e. manipulate) consumers for maximum profit. Over the past few years, behavioral economics has become de rigueur in the ‘business and management’ culture, eliciting a steady stream of mentions everywhere from the Harvard Business Review to click-bait articles. Headlines trumpet its power – “Business strategy hack: behavioral economics” and training academies have emerged to reveal its secrets.

Financial services are no exception and are a particularly fertile environment. As a purely abstract topic to begin with, consumers start out inherently susceptible to external influences. Further, finances are upstream all other economic activity – minor influences here can set off a tidal wave of downstream effects.

Results are predictable.

Some organizations aim to create ‘win-wins’ by pushing consumers towards their own best decisions while coincidentally increasing business. These include the aforementioned investing firms Betterment and Wealthfront, which market themselves as successfully nudging consumers in the ‘right’ direction towards higher savings and long-term returns – of course all while maximizing the consumers business with the firm.

On the whole, most other firms are less benign, or even hostile to the consumer with their nudges. No organization better characterizes this – and today’s ‘fintech’ zeitgeist – than the stock trading service Robinhood. Robinhood has built a business model fueled by trades: the more trades their consumers make, the greater the profit. They have been mercilessly effective at leveraging behavioral economics to manipulate their users:

- Zero Price Effect: Trades are free – users have no easily perceivable barrier to entry, and less intrinsic risk as a result

- Gamification: Digital confetti rains down on completion of each trade, and colorful graphics portray a lighthearted, almost fantasy, atmosphere

- Motivating-Uncertainty Effect: Consumers are spurred to repeated trades with the promise of massive rewards

- Speak-Easy Effect: Complex trading tools distilled in a simplistic user interface instill a false sense of confidence

- Selection Bias: Well-known stocks and fads (i.e. bitcoin) are highlighted over more responsible investments

- Etc.

When confronted about on how it had of trading, Robinhood presented its own take: “Our goal is to help more people take control of their finances by breaking down barriers, … and we remain focused on building products that delight and inform people.” This was, of course, before the well-publicized suicide of a 20-year-old user who was shown he had racked up $700,000 in debt on the platform trading options. The response? Less than a month later Robinhood confirmed an investment raise of $320 million, realizing a valuation of $8.6 billion [2].

saving the soul of financial services

The age-old link between financial independence and individual freedom is beginning to fray as behavioral economics becomes increasingly interwoven with even the most basic financial services. The ‘fundamental right’ of access to the modern financial system rings hollow when it results in those most vulnerable being manipulated into self-destructive tendencies for profit.

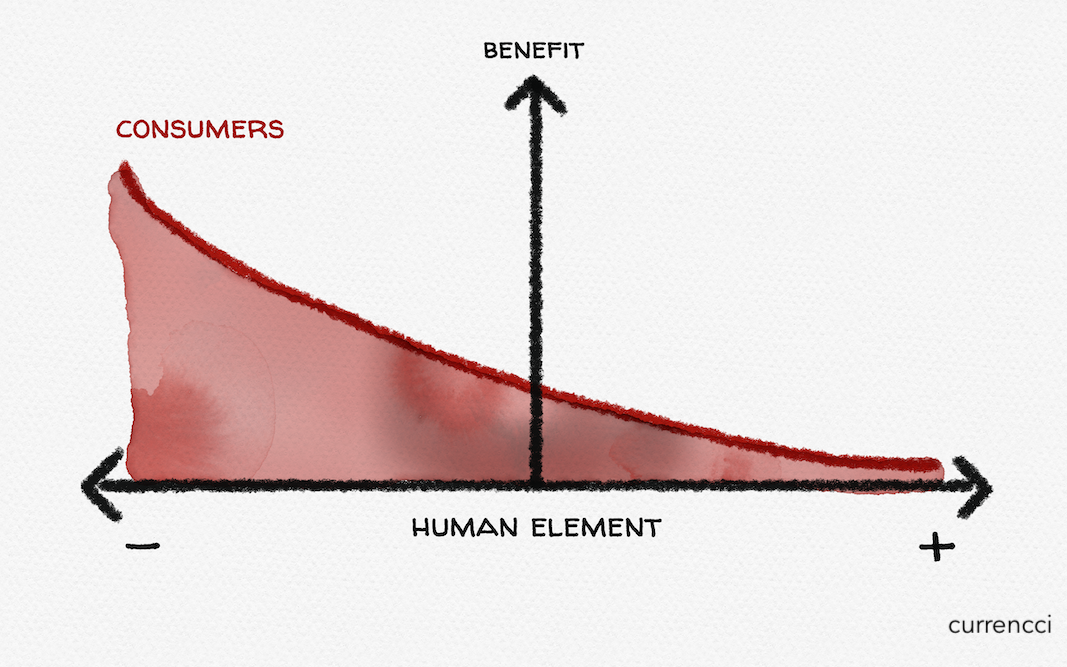

Consumers have no chance as financial service providers increasingly wield the power of behavioral science simply to remain competitive. Despite best efforts of non-profits and governments, it is unrealistic to assume the mass of consumers will learn to know better through financial literacy education.

The industry, not consumers, will instead be the driving force of any change. Unfortunately as it stands, current trends suggests a race to the bottom, eventually halted by heavy-handed regulators who may do more harm than good.

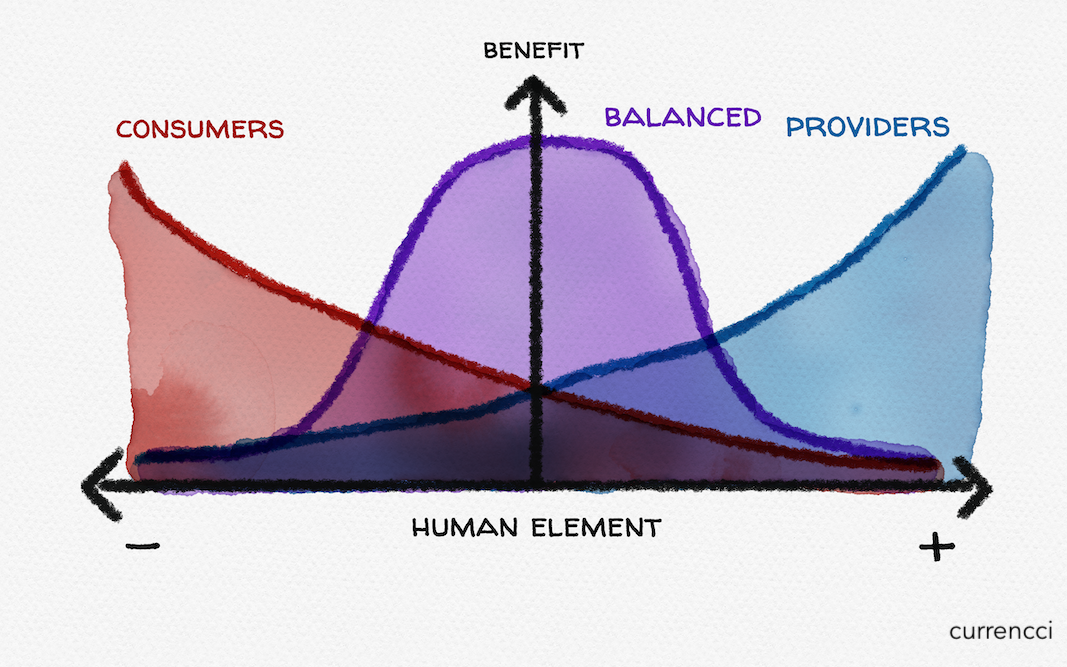

Regardless of how long this takes, it will slow – and potentially halt – innovation and change towards the ideal state: financial services which optimize the individual’s needs and provider returns. To realize its full potential, change must come from within the financial services industry through self-regulation wherein behavioral nudges are explicitly acknowledged and used in an agreed upon, non-exploitive manner. I propose the following tenants as a starting point:

- Professionalism: Financial services product designers must be educated in behavioral economics and the nudges at their disposal to help consumers make better decisions, and avoid harmful ones

- Transparency: Businesses should explicitly acknowledge the main nudges they use, and why

- Accountability: Financial Service providers should be rated for their psychological treatment of their customers

- Acknowledgement: Financial Service providers should have the option to be certified and recognized for deploying behavioral economics in a positive manner

- Contribution: The industry must proactively engage with and support the Behavioral Economics research community to advance and expand the field

With the mechanisms of behavioral science growing clearer each day, financial services are increasingly self-aware of their influence. The question now is when the broader public makes this same realization and its links to financial independence and even individual freedom itself, what will they see? Now is the time for the industry to decide.

I welcome your feedback. Please don’t hesitate to reach out through the contact section of the website if you would like to discuss, comment, or have any suggested edits.

[1] Prior to the WEIRD controversy in the latter.

[2] A separate, element of Robinhood’s business model – an age old practice conducted by other major brokerages – is that it sells its customer’s trades to high frequency trading firms for actual execution. What’s left unsaid is these institutional investors can thus make trades in response to these orders, gaining further advantage over those consumers Robinhood is supposedly uplifting.